Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Duty of care: How to fix the aged care worker shortage calls for more action to be taken to address Australia’s shortage of aged care workers. It recommends that the Federal Government introduce an essential skills visa for occupations facing severe and ongoing worker shortages in the care sector, starting with aged care. This report contributes to the wellbeing, security & participation focus area of CEDA’s Progress 2050 vision for a better future for the next generation of Australians.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- The Federal Government should introduce an essential skills visa for aged care occupations below the wage thresholds in recognition of the ongoing shortage and anticipated growth in demand for workers. The visa would provide a pathway for the same occupations as the aged care industry labour agreement.

- Labour market testing should be abolished for the three occupations covered by the agreement, as they face critical shortage. It can be replaced by regular evaluation of the visa’s effectiveness every three to five years.

- The Government should consider waiving or reducing the Skilling Australia Fund levy for employers sponsoring a worker on an essential skills visa. It should also only be payable once per migrant in cases where the worker moves from one sponsored visa to another, such as from temporary to permanent sponsorship visa.

- The Government should consider making employers’ sponsorship costs payable pro-rata, rather than upfront. This could be in the form of a loading paid to the Government in addition to employees’ regular pay for the duration of the sponsorship.

- The Federal Government, either through the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the Australian Bureau of Statistics or the Department of Health and Ageing, should provide nationally consistent annual data on the aged care workforce, to better support workforce planning.

REPORT HIGHLIGHTS

The aged care sector has faced large structural workforce shortages for many years. As the population ages, the need for aged care workers will continue to grow. But without a strong workforce, we cannot provide older Australians the quality of care they deserve.

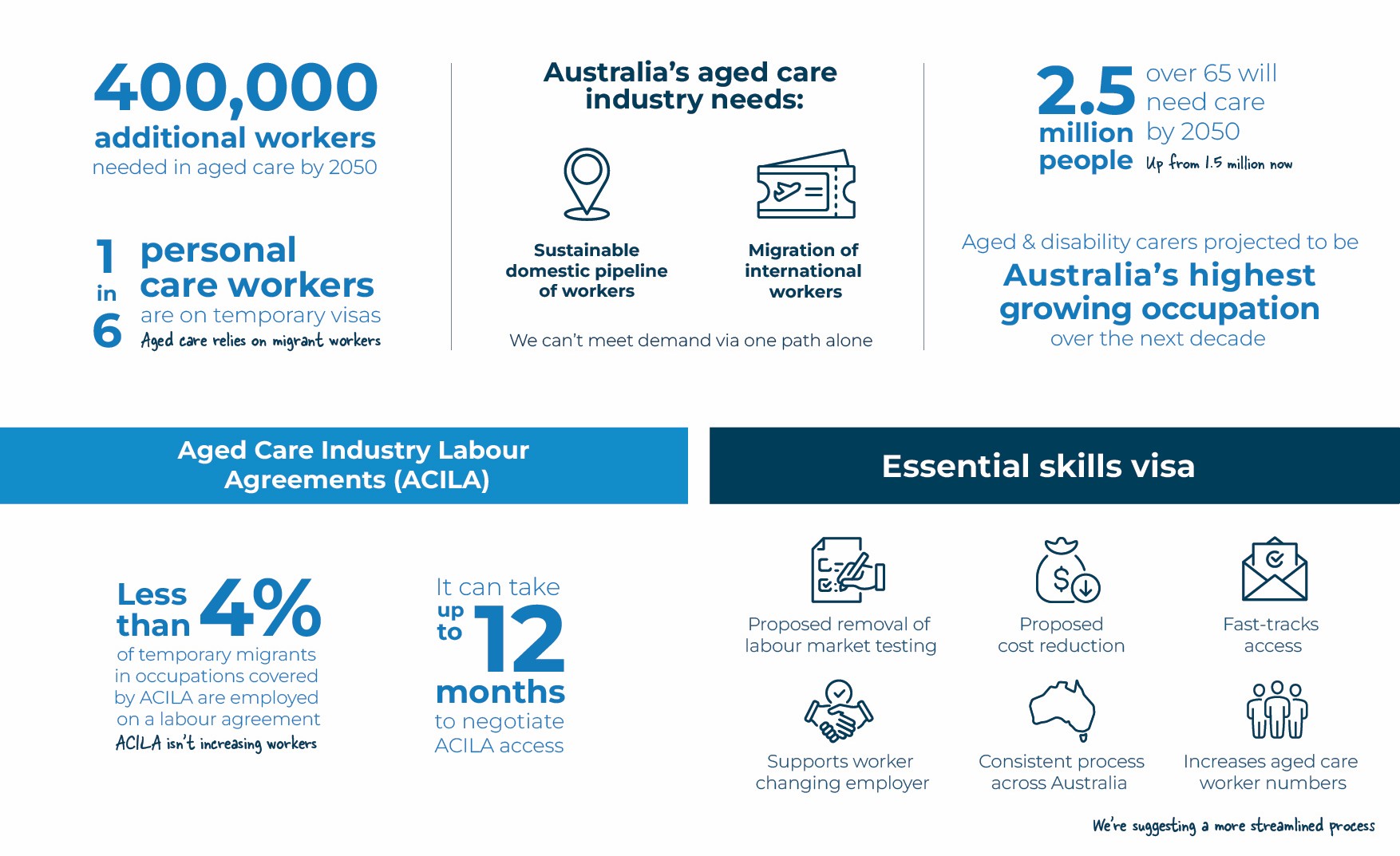

CEDA has previously shown Australia will require at least 400,000 additional workers across residential and in-home aged care by 2050 to meet growing demand. There has not been enough progress to close this gap. This is a long-term challenge that requires a bold response.

The solution to the shortage is multifaceted. Australia must build a sustainable domestic pipeline of aged care workers as a priority. But this alone will not be enough. We must also continue to explore how to optimise migration to sustainably grow the sector's workforce. Given the size of the shortages, it is not feasible to meet demand through domestic training and hiring alone.

The Federal Government acknowledged the strong role migration plays in the sector in its 2023 Migration Strategy, committing to looking at an essential skills visa pathway for lower wage migrant workers in sectors with critical workforce shortages, such as personal care workers in aged care. CEDA advocated for such a visa in its submission to the Migration Review. There has been no noticeable progress on this pathway.

The Government has sought to respond to the need via labour agreements, initially through company-specific agreements and then by introducing the Aged Care Industry Labour Agreement (ACILA), which covers three key occupations: nursing support worker, personal care assistant and aged or disabled carer.

These agreements aren’t bringing in anywhere near enough workers to fill the gap and do not meet the underlying need for a new visa pathway. We estimate that in the June quarter of this year, less than four per cent of temporary migrants in these occupations were in Australia on a labour agreement.

Most migrant workers continue to come into the sector as sideways entrants. The vast majority of migrant workers in the occupations covered by the agreement came to Australia on temporary visas for other purposes, such as student, partner or working holiday visas.

We’ve found providers are using labour agreements to retain a small number of existing staff already in the country, rather than increasing the overall number of workers in the sector by attracting additional staff from overseas.

The ACILA is not meeting the needs of the sector – it is not bringing in enough workers to meet demand. Consultation with industry also suggests there is unlikely to be a significant increase in uptake of the scheme.

This approach must change if we are to meet the aged care needs of the future.

This is not a short-term problem in need of a temporary fix. It is long-term in nature. We need to pull all levers, including migration, to increase the workforce.

The Government should pursue an essential skills visa for aged care workers as a priority.

THE AGED CARE WORKFORCE NEEDS TO GROW RAPIDLY

As Australia’s population ages, more people will require aged care. We estimate around 2.5 million people aged 65 and over will need some form of care by 2050, up from 1.5 million now.

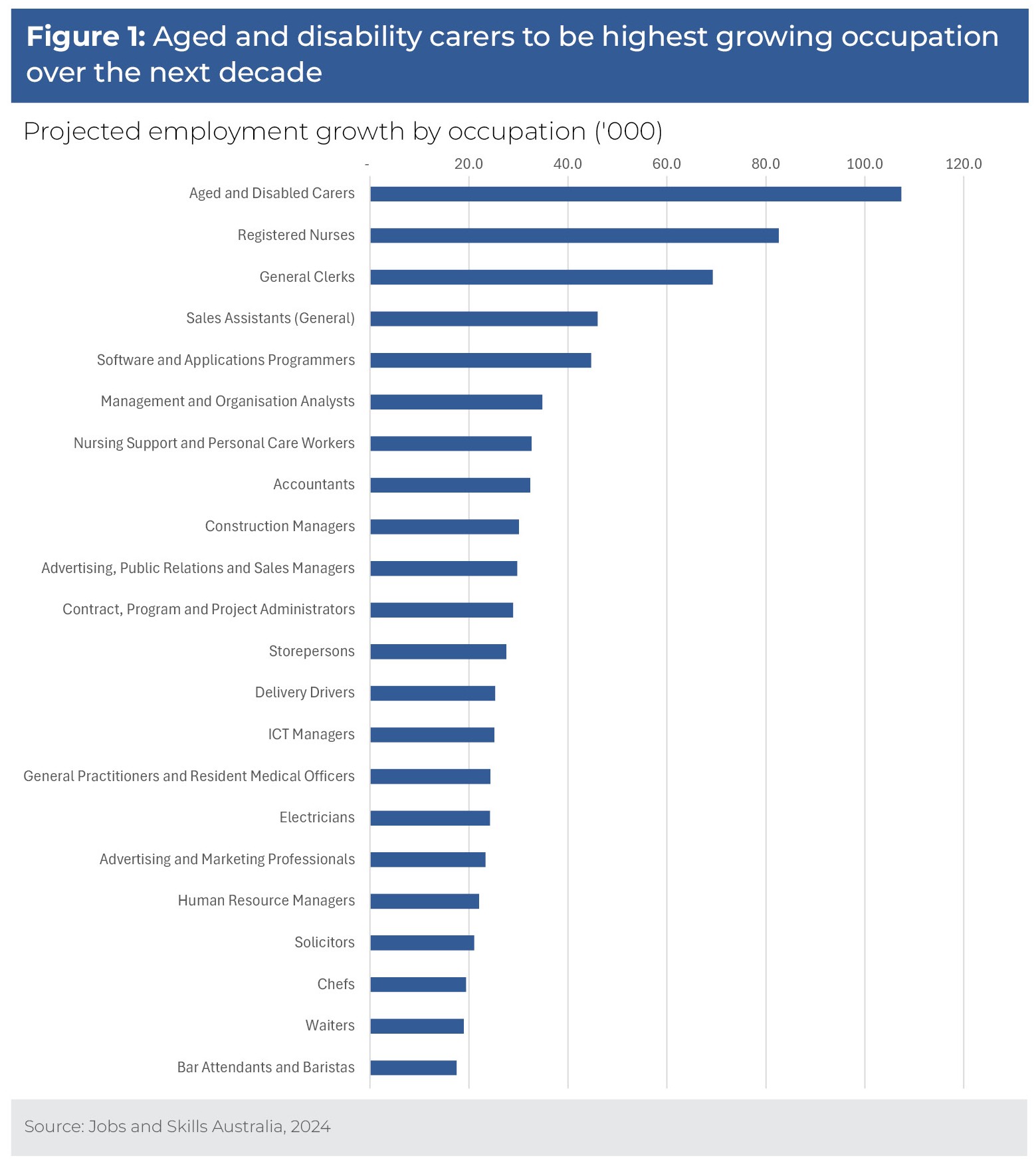

Jobs and Skills Australia projects aged and disability carers to be the highest growth occupation in Australia over the next decade based on general demand for these services (Figure 1), consistent with CEDA’s 2021 projections of significant shortages in the sector over the next 25 years.

These projections are all likely to be on the conservative side, as they don’t take into account the Federal Government’s legislated increase in the quality and quantity of care, particularly through in-home care, where aged care is provided at a person’s home rather than in a residential facility. This will further increase worker demand.

More needs to be done to attract workers

There has been some improvement to conditions in the sector to attract and retain both Australian and migrant workers. In July 2023, the minimum wage was increased by 15 per cent for aged carers, nursing support workers and personal care assistants, bringing wages more into line with those for disability workers and higher than those for retail or beauty therapy workers. CEDA advocated for higher wages in 2021.

In the nearly two years since the wage increase, the national aged and disability carer workforce grew by 35 per cent. Due to a lack of detailed data, we don’t know how much of that growth has been in aged carers specifically.

Consultation suggests that the wage increases have improved retention and turnover, but are not attracting significant numbers of new workers. We are still well short of the number of workers required, as service demand continues to increase.

Pay and employment conditions will need to improve further to build a larger, more sustainable pipeline of Australian workers.

Providers also need to increase training of both new and existing staff, and to invest in new technology and innovation. The full recommendations of CEDA’s 2021 report should be implemented across each of these areas.

Given the magnitude of the challenge, however, the Australian workforce alone will not be nearly enough to reverse the shortage.

Aged care relies on migrant workers

Aged care has traditionally relied heavily on migrant workers. We estimate that around 70,000 – or one-in-six – personal care workers in the sector are on temporary visas. This is a conservative estimate.

Aged care is not alone in having a large proportion of migrant workers. Industries such as healthcare, community services, construction and information and

communication technology all employ large numbers of temporary migrants to help ensure they can reliably deliver the services Australians need and expect.

Where there are genuine shortages of workers, as is clearly the case in aged care, the system should enable more streamlined and targeted migration.

A push to attract more migrants into aged care should consider the impact on both the Australian labour market and on the migrant’s home country. While source countries may lose workers through increased migration to Australia, they can benefit from the further training workers receive in Australia if they return home. They also benefit from the remittances that workers often send home.

Migration must be part of the answer to the workforce shortage, alongside improved working conditions, a strong domestic training pipeline and upskilling the current workforce.

LABOUR AGREEMENTS ARE NOT THE SOLUTION

The aged care occupations facing the most severe shortages, primarily personal care workers, do not qualify for other skilled migration visas as their annual salary is below the minimum rate, which currently sits at $76,515.

As a result, aged care providers have had to use labour agreements to bring in workers. Initially, each provider had to negotiate a bespoke company-specific agreement with the Government and unions to sponsor a migrant. The process was slow, and uptake was low.

Recognising this, the Government introduced the Aged Care Industry Labour Agreement (ACILA) in May 2023.

The agreement enables migrants to fill vacancies in three occupations at the heart of the aged care workforce:

- Aged or disability carers;

- Personal care assistants; and

- Nursing support workers.

Its aim is to streamline the negotiation and sponsorship process for employers, who can access the agreement by signing a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the relevant union: the Health Services Union (HSU), the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) or the United Workers Union (UWU).

In the two years since the ACILA was introduced the number of agreements has risen from 10 company-specific agreements to a total of 142 at the end of June 2025, encompassing both company-specific agreements and ACILA.

While it is positive that more agreements are in place, Department of Home Affairs data indicates that just 2426 temporary migrants were sponsored under all agreements in the sector at the end of June 2025. This figure also includes some workers in Australia under an additional regional labour agreement.

In other words, less than four per cent of all temporary migrants working in the three qualifying occupations have been sponsored under a labour agreement. This is less than one per cent of all workers in these occupations, both Australians and migrants. This is not a meaningful contribution to fixing the shortages in the sector. Most migrants working in aged care continue to enter the sector through other visa streams.

Labour agreements are too burdensome

Consultation with aged care providers suggests the low uptake has been driven by the difficulty of implementing agreements.

The ACILA was intended to streamline processes. In practice it is burdensome and complex to negotiate and implement. It requires demonstrating that occupations cannot be filled in the domestic market and cumbersome negotiations with local unions that must satisfy a range of criteria. It can take more than 12 months in some instances.

The process is also inconsistent across states and varies according to the unions involved. This means there is no ability to streamline the process across the industry or build on agreements already in place.

There is little guidance for providers on how to navigate the process effectively across jurisdictions. Given the inconsistent advice and lack of information, employers cannot rely on previous negotiations as an indicator of current or future processes.

Given this burden, many employers have chosen not to use the agreements.

AGREEMENTS ARE RETAINING RATHER THAN ATTRACTING NEW WORKERS

Although the aged care labour agreement was intended to encourage providers to sponsor migrant workers from overseas, many providers are using the agreement to sponsor existing staff already in Australia on temporary visas such as student, partner or working holiday visas.

Department of Home Affairs data shows that in 2024-25, only 10 per cent of the sponsored temporary visas granted under an aged care labour agreement went to applicants outside Australia. In other words, 90 per cent of visas under the agreement went to workers who were already in Australia. This shows the agreement is barely adding to the overall size of the workforce.

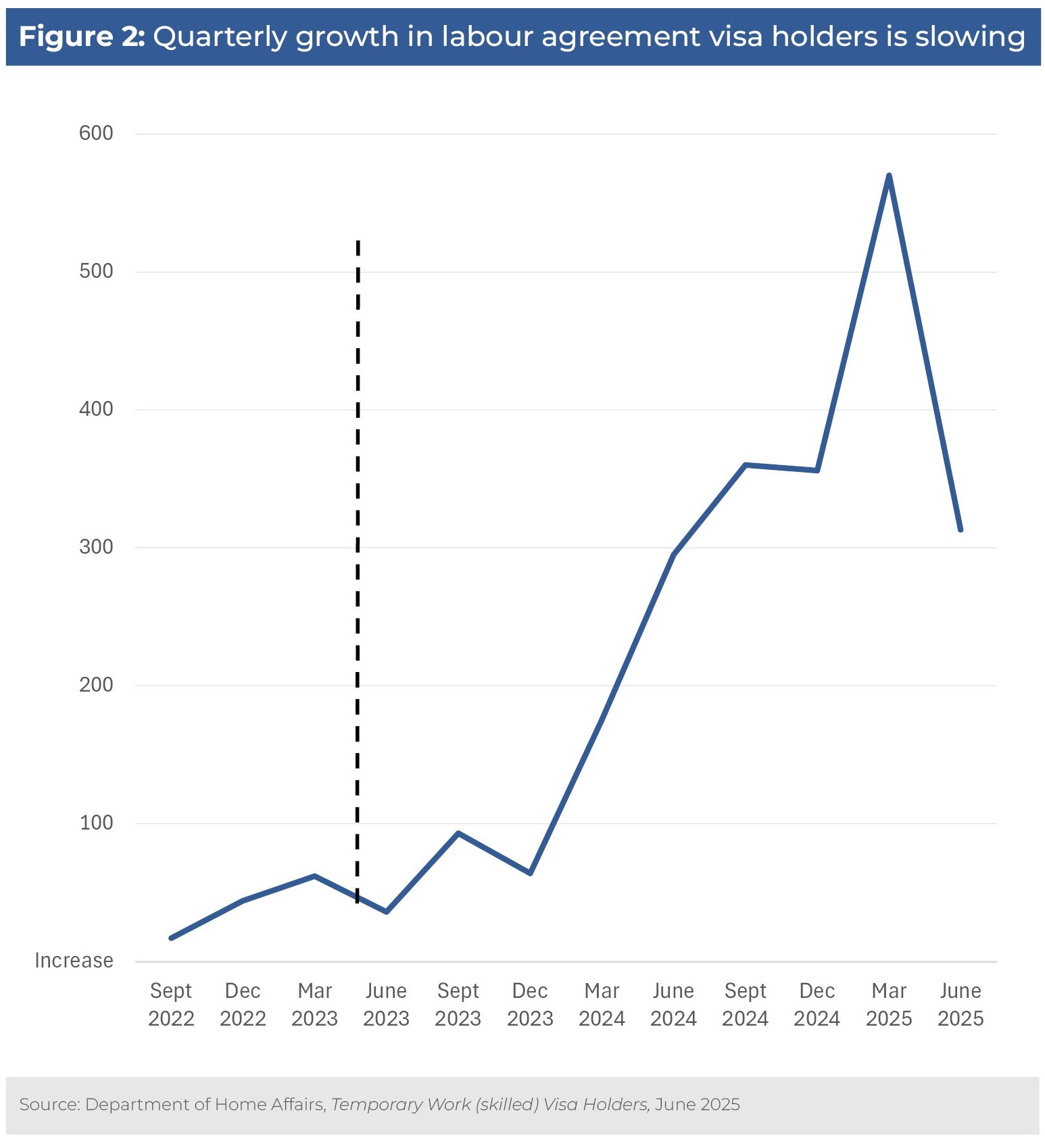

While growth in the number of workers sponsored under labour agreements accelerated after the ACILA was introduced, it has slowed, with the rate of growth slower in the June 2025 quarter than in the preceding three quarters (Figure 2).

Providers told us they use the agreement sparingly to sponsor high-performing personal care workers to keep them in Australia, as sponsorship offers a pathway to permanent residency.

They also said they did not intend to use the agreements to bring in new workers from overseas, unless they had no other option to fill critical vacancies. They said the high costs of sponsoring a visa made it too risky to bring in new, untested employees.

The agreement is clearly not achieving its objective of streamlining the recruitment of qualified workers from overseas where qualified Australians are not available. It is neither meeting the needs of the industry, nor significantly reducing workforce shortages.

Instead of relying so much on sideways entrants to the workforce, Australia should actively target migrants with appropriate qualifications and experience who want to come to the country to work in aged care.

Labour agreements restrict worker mobility

While migrants sponsored under the aged care agreement can change employers, they can only work for an organisation that also is party to the agreement. This limits their options, given the relatively small number of agreements in place.

This not only creates rigidities in the labour market and reduces worker mobility, it also increases the possibility of exploitation of workers who are unable to secure alternative employment.

Stability is important for both employers and employees. However, restricting mobility is not the answer. Instead, we should do more to fix the broader underlying issues causing poor staff retention, such as low pay and challenging working conditions.

The recommendations of the aged care royal commission have addressed some of these issues. Employers are also using other measures such as above-award pay, access to professional development and training and flexible working conditions.

Abolishing the aged care labour agreement in favour of another standard visa available to all aged care providers would also help to improve mobility.

Visa costs are too high

In consultations, providers consistently nominated cost as the biggest disincentive to sponsoring migrant workers, whether through a labour agreement or not.

The lengthy negotiations required for a labour agreement create an additional burden on top of the financial cost of a visa.

Costs can vary but generally exceed $3000 each for both the employer and the migrant, comprising application fees, nomination charges and the Skilling Australia Fund levy. This is before any agency, legal, or English-literacy fees are incurred.

The Skilling Australia Fund levy of $1200 to $1800 per year of sponsorship makes up a substantial part of the employer’s costs. Its purpose is to ensure Australia has the resources to provide training in areas of skills shortage. All employers nominating a sponsored migrant on any skilled visa type must pay the levy upfront. They pay it twice if a worker moves from a temporary sponsorship visa to permanent residency.

There is always going to be a cost to the Government for providing visas and we should continue to ensure cost recovery. However, the costs here are likely to outweigh the sector’s actual training costs. The Government should consider waiving or reducing the Skilling Australia Fund levy for employers sponsoring a worker on an essential skills visa, and it should only be payable once per migrant.

The Government also should consider making employers’ visa costs payable pro-rata, rather than upfront. This could be in the form of a loading paid to the Government in addition to employees’ regular pay for the duration of the sponsorship. In this way, if the worker moves employers, the hiring employer does not bear the full cost of sponsorship.

LABOUR MARKET TESTING IS NOT EFFECTIVE AND SHOULD BE REMOVED

It is quicker, easier and less costly to hire Australian workers than bring workers in from overseas.

Despite this, employers in all industries must undertake labour market testing before sponsoring a migrant worker or signing up to a labour agreement.

This is to ensure local workers have adequate opportunity to apply for a vacancy and to confirm that there are genuine shortages of local workers.

Employers must advertise vacancies for a minimum of four weeks and show they have exercised due diligence in trying to secure workers domestically.

Labour market testing has been simplified for the ACILA. Nevertheless, it is still an additional compliance obligation that takes up administrative resources and lengthens the time it takes to start sponsoring a migrant worker.

Further, by law and under enterprise agreements, Australians and migrant workers must receive the same pay and conditions. It is illegal to pay a migrant worker less than an Australian.

The cost of visa sponsorship further increases the incentive for employers to seek Australian workers before looking overseas.

Industry consultation suggests labour market testing is an additional compliance burden and generally seen as unnecessary, potentially resulting in tokenistic job advertisements in aged care, given the shortage of Australian workers in the sector.

Labour market testing should be abolished for the aged care sector.

AN ESSENTIAL SKILLS VISA IS A MORE STREAMLINED APPROACH

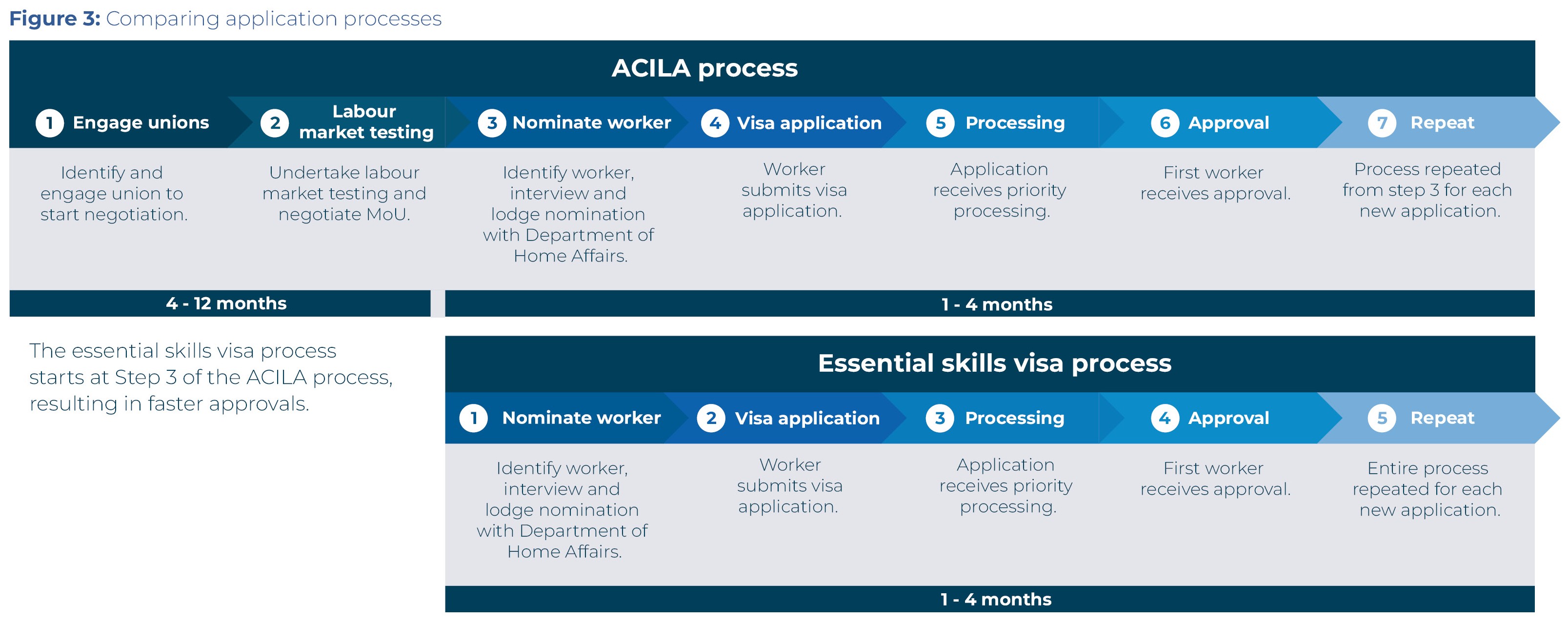

Our proposed essential skills visa would target the same occupations as the ACILA but would enable all aged care providers to offer sponsored visas in both residential and in-home care without having to go through the negotiations required under the labour agreement (Figure 3). This would save substantial time and resourcing upfront – in some cases a year or more – and resourcing required to negotiate an MoU under the ACILA. It would be a direct and streamlined process across the industry, rather than by individual negotiation.

If implemented well, including a reduction in the cost of sponsoring workers, this visa would help to address the sector’s acute worker shortages by increasing the number of migrants who come to Australia to work in aged care. Workers already sponsored under the ACILA could transfer to the new visa. It would also allow greater mobility for workers, as any aged care provider could sponsor their visa.

The Government should enable employers to find qualified migrants through an online system such as the Department of Home Affairs’ SkillSelect website.

Prospective migrants would use the system to register their interest in being nominated for a skilled visa and provide details of their experience and qualifications. Employers would use it to identify suitable applicants and start a sponsorship process after assessing the applicant’s suitability.

Having such a platform to assess overseas applicants should encourage employers to bring in more workers, rather than relying so heavily on migrants already in Australia. This would further enhance the essential skills pathway.

SkillSelect is currently used for regional and independent business visas, rather than employer-nominated temporary visas, although it can support applications for these visas. It should be used for the essential skills visa.

The scheme should collect data on migrant experiences and career pathways, with built-in evaluation. This will help to ensure the visa is effective and enable changes to be made if required.

Every three to five years, a review should evaluate if industries and occupations still have workforce shortages big enough to qualify for the visa category. It should also ensure the visa is not having unintended consequences such as suppressing wages, discouraging training of local workers, or otherwise disadvantaging local workers. Any employers found to have breached employment conditions for Australian or migrant workers should no longer have access to the scheme.

The evaluation should also consider where migrants are coming from under the scheme, and monitor the impact on the source countries.

More timely and targeted data

Workforce planning is challenging in aged care as there is little nationally consistent and representative data on the workforce.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare carries out a biennial survey and census on the aged care workforce, however the releases have been inconsistent and the data is not comprehensive enough to allow for good decision-making.

Given the worker shortages in the sector, developing consistent, annual national data should be a priority to enable analysis of the workforce, including visa status and vacancies.

To be most effective, annual surveys on the aged care workforce need to be nationally consistent and representative of the whole workforce. This would allow proper evaluation of new initiatives, including the ACILA and an essential skills visa, and better targeting of future strategies.

Data and evaluation will be supported by new ABS data currently being developed that disaggregates disability and aged care occupations, however more surveys are required for a detailed picture of the workforce.

CONCLUSIONS

The solution to the aged care workforce challenge is multifaceted.

Providers and the Government should continue efforts to build a sustainable pipeline of Australian aged care workers as a priority, ensuring that pay and conditions are appropriate to attract new workers while also retaining the existing workforce.

CEDA has previously made recommendations to improve domestic training, retention and technology to increase the workforce. But this alone is not enough.

Where shortages persist, our migration system should be able to respond rapidly.

Despite the good intentions behind its creation, the aged care industry labour agreement has not been effective at bringing new workers into Australia. It has

helped providers retain existing migrant staff by offering them a new visa sponsorship pathway, and this is a positive outcome. But there are other ways to retain staff, including better career progression, training, pay and conditions and flexible working arrangements.

An essential skills visa should be introduced, along with an online system to match prospective workers overseas with Australian employers, to help ensure its success.

Rigorous evaluation should be undertaken to ensure the visa pathways are meeting their objectives and that migrants, Australian workers and providers are all benefiting.

Author

Tim Kane

Senior Economist