PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

Back to all opinion articles

19/04/2018

According to the OECD, 17 per cent of Australian young people leave secondary school without achieving basic educational skill levels. They conclude that eliminating school underperformance would reap enough fiscal benefits to pay for the country’s entire school system.

Educational inequality takes many forms, and is a problem because it stunts the potential of young people. This underachievement has negative impacts for young people themselves, which in turn has negative impacts for the larger society. Low educational outcomes are related to diminished health, unemployment, low wages, social exclusion, crime and incarceration, and teenage pregnancy.

Inequalities between students from different social backgrounds already exist when they start primary school. Worryingly, these inequalities increase as students progress through the education system.

This week, the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) published a report about inequality and its negative effects for people and the larger society. The report includes chapters on inequality in education, workplaces, geographic inequality and inter-generational inequality.

Inequality in Australian schools

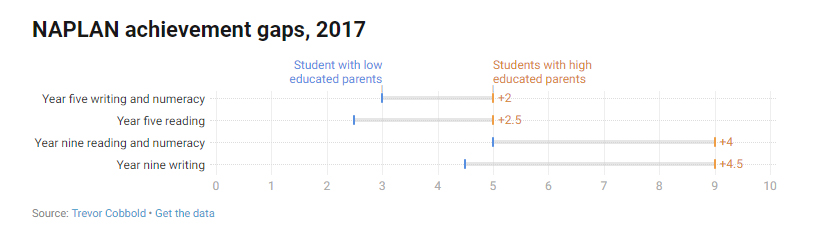

A recent report shows NAPLAN achievement gaps between year five students from high and low educated parents are the equivalent of more than two and a half years of learning in reading and about two years in writing and numeracy. For year nine students, the gaps are even larger: about four years in reading and numeracy, and four and a half years in writing.

Get the data

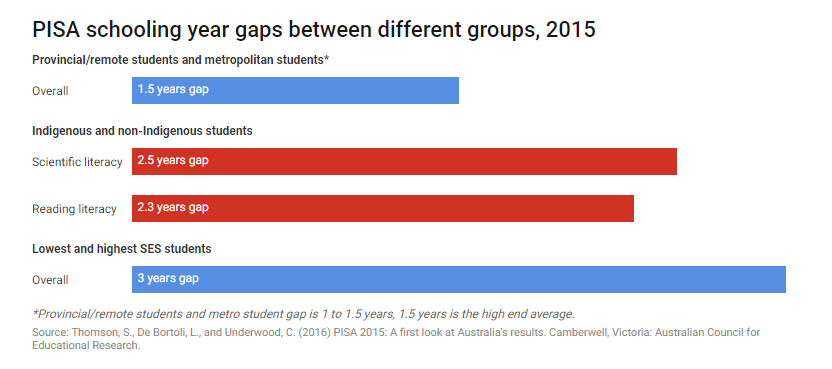

Data from PISA shows similar inequalities. Australian students from the highest socio-economic status (SES) quartile substantially outperform those from the lowest SES quartile in reading, maths and science. The equity gap represents almost three years of schooling in all three domains.

These inequalities of educational outcomes are partly driven by poverty and disadvantage outside the school. But these socioeconomic inequalities are then amplified by schooling. This is because socially advantaged students in Australia often receive more educational advantages than their less privileged peers, not less.

Inequalities of educational opportunities and experiences are a result of socially segregated schools. Australia has one of the largest resource gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged schools in the OECD. Australia has large the largest gap in the shortage of teachers between disadvantaged and advantaged schools among all OECD countries.

Disadvantaged schools in Australia also have far fewer educational materials (books, facilities, laboratories) than high SES schools. This gap is the third largest in the OECD, with only Chile and Turkey showing larger inequalities between schools.

To tackle underachievement, we need to do two things

- Give early, targeted and intensive support to students as soon as they start to fall behind. This is what Finland does, with almost 30 per cent of its students receiving such an intervention at one time or another. It’s one of the best ways to ensure students don’t fall between the cracks. But it requires resources, so we need to give more money to the schools and students who need it. This is where needs-based funding plays a role.

- Make our schools more socially integrated. It’s the most effective way to raise achievement. A socially mixed or average student composition creates conditions that facilitate teaching and learning. Middle-class and/or socially mixed schools are also much less expensive to operate because they have fewer students with high needs. Less expensive running costs frees up funds which can be used for targeted and intensive support for students who need it.

How do we reduce school social segregation?

If we look to Commonwealth countries that have less segregated schooling than Australia, such as New Zealand, Canada and the UK, we can see two inter-related things. They have a much smaller proportion of schools that charge fees, and smaller qualitative differences between schools in terms of their facilities and resources.

These countries show both of these things can be done while maintaining diverse schooling options. We can still have schools with different faiths, philosophies and orientations, in addition to a strong and robust public school system.

While the latest federal school funding approach is moving in the right direction, it’s still based on an inherent contradiction that reduces its effectiveness. On the one hand, we have a funding policy that promotes unequal resourcing between schools via a large fee-paying school sector. This inevitably leads to a socially stratified school system, which increases educational inequalities and underachievement.

We then try to mitigate those negative consequences of our funding policy with a different funding policy (redistribution via needs-based funding). The two prongs are working against each other, which is not only educationally ineffective but also fiscally inefficient.

Needs-based funding is necessary, but it can only do so much. It’s much more effective if we don’t have schools with high concentrations of poverty and disadvantage. Needs-based funding will not be much more than a band-aid if it’s not accompanied by greater structural reform in the way we fund and organise schools.

Needs-based funding redistributes some funding from schools with lower needs to those with greater needs, but it will do little to reduce school segregation. And so the result of our efforts to reduce underachievement will be modest at best.

This article was originally published on The Conversation, 20 April, 2018 to coincide with the release of CEDA's report.

CEDA research: Read and download How unequal? Insights on inequality.

CEDA Members contribute to our collective impact by engaging in conversations that are crucial to achieving long-term prosperity for all Australians. Find out more about becoming a member or getting involved in our work today.