Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

28/10/2022

Forecasts by economic institutions such as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) set the expectations of markets, businesses and consumers. In the housing market, the risk of rising interest rates can mean planned purchases are no longer feasible, or an existing purchase should be sold to reduce repayments.

This year, the RBA drew sharp attacks on its credibility when it changed its monetary policy stance much earlier than its forward guidance had indicated, adding weight to calls for an independent review of the central bank.

So, how did we get here?

Since the 1990s, inflation targeting has been used by the RBA to support the economic prosperity and welfare of Australians. The main tool it uses to achieve this is the adjustment of short-term interest rates. By changing the cash rate on interbank loans, the RBA can influence the cost of borrowing money, transmitting monetary policy through to economic activity and inflation.

Consumers and businesses don’t always respond the same way that conventional monetary policy predicts, however, as demonstrated by the uncertainty of the Global Financial Crisis and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

As part of its deliberations on the cash rate, the RBA also issues forward guidance to communicate the context of its decisions and what the future path of any change to interest rates is likely to be. This is known as one of the “unconventional” tools the RBA used in the past decade to signal future movements, as cash rates approached zero and there was limited scope to reduce rates further.

The goal of forward guidance is to reduce uncertainty, allowing people to confidently make large, long-term investments. The following statement from October 2021 was an effort to do this (emphasis added):

“The Board is committed to maintaining highly supportive monetary conditions to achieve a return to full employment in Australia and inflation consistent with the target. It will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range. The central scenario for the economy is that this condition will not be met before 2024.”

Source: 5 October 2021 Statement on the Monetary Policy Decision

This statement indicates that the RBA did not expect to increase rates for at least 14 months, in line with its central forecast for inflation. The RBA issued similar statements in subsequent months.

The tone and context of this statement could be criticised for not providing the same level of nuance as previous statements. The RBA likely decided to use stronger language and fewer caveats to boost confidence, but in doing so increased the chance that its forecasts would be incorrect. October 2021 was an uncertain time – it was not yet clear Australia’s economy and communities would bounce back from cascading lockdowns and a delayed vaccination rollout.

This trade-off by the RBA – boosting confidence yet potentially over-committing to uncertain forecasts – was made clear when, seven months later, the central bank’s May 2022 monetary policy decision signalled a striking change of approach, reflecting a dramatic rise in inflation in Australia:

“At its meeting today, the Board decided to increase the cash rate target by 25 basis points… Inflation has picked up significantly and by more than expected, although it remains lower than in most other advanced economies… The Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time. This will require a further lift in interest rates over the period ahead.”

A casual reading of the RBA’s earlier statement from October could have missed the crucial caveat that the central bank would only keep interest rates unchanged if its central scenario was accurate.

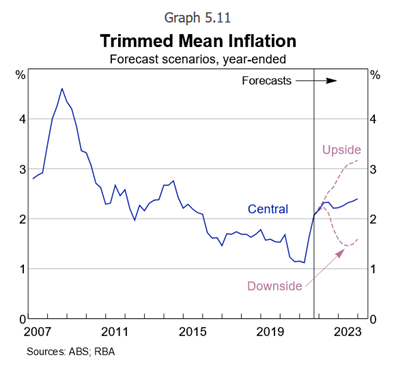

This central scenario is only a forecast. It provides a view on the most likely outcome from a wide range of possible outcomes. From the more detailed Statement of Monetary Policy in November 2021, the RBA outlined a central scenario (an inflation rate of 2.3 per cent by end of 2022) as well as two other possible outcomes:

- An upside of stronger economic growth and higher inflation driven by confidence due to accumulated savings, increases in house prices and reduced COVID impacts (3.2 per cent by end of 2022).

- A downside of lower inflation, low growth due to lingering uncertainty about new COVID variants and vaccine efficacy against these in early 2022 (1.7 per cent by end of 2022).

These two scenarios are mapped out in the inflation forecast graph from November 2021:

So what happened in the six months between November 2021 and May 2022?

There were price shocks in commodities such as oil, gas and wheat due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, increased domestic economic activity and a tightening of labour markets. Inflation rose dramatically as a consequence, hitting 3.7 per cent in March 2022, nine months before even the upper limit forecast for high inflation by the end of 2022 (3.2 per cent) and then climbed even higher to 4.9 per cent in June and 7.2 per cent in October. Even the most hawkish scenarios did not predict the level of inflation seen this year. This gap between the forecast and reality is shown in the chart below.

Consumers and businesses are currently expected to understand the context and language used by the RBA in its statements. But this context may not directly accompany monetary policy statements, arising instead from other speeches and reports.

Consumers may need more support to use forward guidance to make financial decisions. The former chief economist at the Bank of England, Andrew Haldane, described this as solving the twin deficits of public understanding and public trust, as the public is unlikely to trust something it does not understand.

There may be a case for the RBA to improve public understanding by emphasising and explaining the caveats it uses in its statements, much like how disclaimers must accompany financial advice. Without additional context, an individual such as a first homebuyer may not understand the complexity and subtlety of economic terms such as “the central scenario”.

The effectiveness of RBA communications is one of the issues to be considered by the review of the central bank’s performance.

With the RBA expected to continue its fastest pace of rate rises since 1994 on Melbourne Cup Day, we must consider the context in which its projections are made. If households and businesses are not reducing spending following recent rate rises, or supply price shocks become permanent instead of transitory, we may see the RBA go harder and faster in future rate rises.

CEDA's new course, Economics for Non-Economists, is designed to introduce participants to the fundamentals of economics. In addition to covering fiscal and monetary policy, the course delves into macroeconomics and the GDP formula; inflation and unemployment; and demand, supply and equilibrium in markets. More details about this self-paced course can be found here.

.jpg)