Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Back to all opinion articles

08/04/2019

The big news in the 2019–20 Federal Budget was not that economic conditions would boost the Government’s fiscal position but that two-thirds of the benefits would be used to increase spending or reduce taxes. That is, of course, if the Government is successful in its re-election campaign.

The underlying cash balance is expected to be a deficit of $A4.2 billion (-0.2 per cent of gross domestic product) in 2018–19, which is very similar to the $A5.2 billion deficit projection made at the time of the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook in December.

Extra receipts for the Government were offset by $A3 billion of immediate spending. The measures include more than $500 million for Queensland flood assistance, just over $300m for aged care and another $300 million for the Energy Assistance Payments. A substantial $1.275 million of local government grants were brought forward into 2018-19 (read: a way of making the 2019–20 surplus larger).

From there, the underlying cash balance increases to $A7 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP) in 2019–20, but it would have been bigger if not for the $1.6 billion of policy spending. Significantly this involves the low- and middle-income tax offset which the Government plans to increase by $A550 from $A530 to a maximum of $A1080. It will be paid to eligible individuals after they lodge their 2018–19 tax returns.

The surplus projections rise to $A11 billion in 2020–21 and $A17.8 billion in 2021–22. In 2022–23 when the tax cuts become substantially larger, the underlying cash surplus declines slightly to $A9.1 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP).

The budget papers also note that the underlying cash balance builds to one per cent of GDP through to 2026–27.

The economic forecasts underpinning the Budget look reasonable in the short term and further out look quite conservative. As expected, Treasury has made a big upward revision to the terms of trade in 2018–19 due to unexpected positive commodity price moves this financial year. As noted this has been responsible for a large part of the near-term upward revisions to receipts.

Treasury now expects a four per cent rise in 2018–19 (compared to a previous expectation of 1.25 per cent rise) but then forecasts a fall of 5.3 per cent in the terms of trade for 2019–20 (compared to a previous expectation of six per cent fall). This compares to ANZ Research’s expectations of a 5.5 per cent increase in the terms of trade in 2018–19 and a 2.6 per cent fall in 2019–20.

Consequently, ANZ Research sees stronger nominal GDP growth of 5.3 per cent in 2019–20 compared to Treasury’s 3.6 per cent.

Treasury estimates year-average real GDP growth of 2.75 per cent in 2019–20, revised down from a three per cent forecast at MYEFO in December 2018. In ANZ Research’s view, real GDP in 2019–20 will be weaker at 2.2 per cent (year-average).

Treasury’s employment growth forecast of 2.1 per cent through the year to June quarter 2020 is a touch stronger than our 1.8 per cent. Treasury’s wage forecast for 2019–20, which ANZ Research has long-thought too strong, was revised down to 2.75 per cent from three per cent, between MYEFO and Budget. It is still stronger than ANZ’s forecast of 2.3 per cent, however.

Capital spending was revised up in the Budget compared to MYEFO, by $A9 billion over the 2018–19 to 2021–22 years. Around $A6 billion of this was due to higher capital grants to the states and territories, with financial asset investments up by a net $A3 million. The profile of government capital spending is still expected to fall as a share of GDP over the coming four years despite the increases.

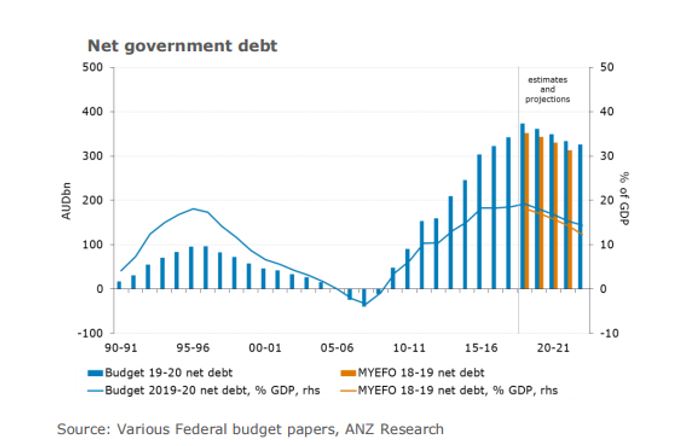

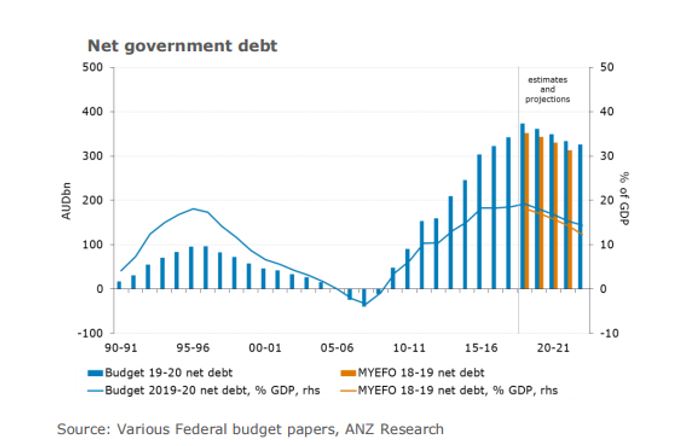

An increase in the value of Australian Government Securities due to lower yields than were assumed at the time of MYEFO, increases net debt in the 2019–20 financial year to 19.2 per cent of GDP (the previous projected peak was 18.5 per cent of GDP in 2017–18). But thereafter, with a mild improvement in the underlying cash balance over the coming four years, net debt as a share of GDP is expected to fall to 14.4 per cent of GDP by 2022–23.

The Government’s projections have an elimination of net debt by 2029–30.

With the Parliamentary Budget Office highlighting the drawbacks of the net debt measure as an indicator of fiscal sustainability, we also consider net financial worth. There has been a widened gap between net debt and net financial worth in recent years, but a projected recovery in this measure also, to -19.7 per cent of GDP by 2022–23.

This Budget shapes the outlook for an ALP Government’s fiscal agenda. We know that an ALP budget would have $1 billion more for low income earners straight away but tax cuts for mid-high income earners would be cancelled.

Other key ALP policies would limit the tax benefits for new property investors who claim losses on their property income from established dwellings and lowers the capital gains tax discount from 1 January 2020. Tax refunds for share investors who do not pay tax would also be eliminated.

The ALP has said it would issue a mini-budget in the third quarter of this year if it were to win office.

The underlying cash balance is expected to be a deficit of $A4.2 billion (-0.2 per cent of gross domestic product) in 2018–19, which is very similar to the $A5.2 billion deficit projection made at the time of the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook in December.

Extra receipts for the Government were offset by $A3 billion of immediate spending. The measures include more than $500 million for Queensland flood assistance, just over $300m for aged care and another $300 million for the Energy Assistance Payments. A substantial $1.275 million of local government grants were brought forward into 2018-19 (read: a way of making the 2019–20 surplus larger).

From there, the underlying cash balance increases to $A7 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP) in 2019–20, but it would have been bigger if not for the $1.6 billion of policy spending. Significantly this involves the low- and middle-income tax offset which the Government plans to increase by $A550 from $A530 to a maximum of $A1080. It will be paid to eligible individuals after they lodge their 2018–19 tax returns.

The surplus projections rise to $A11 billion in 2020–21 and $A17.8 billion in 2021–22. In 2022–23 when the tax cuts become substantially larger, the underlying cash surplus declines slightly to $A9.1 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP).

The budget papers also note that the underlying cash balance builds to one per cent of GDP through to 2026–27.

The economic forecasts underpinning the Budget look reasonable in the short term and further out look quite conservative. As expected, Treasury has made a big upward revision to the terms of trade in 2018–19 due to unexpected positive commodity price moves this financial year. As noted this has been responsible for a large part of the near-term upward revisions to receipts.

Treasury now expects a four per cent rise in 2018–19 (compared to a previous expectation of 1.25 per cent rise) but then forecasts a fall of 5.3 per cent in the terms of trade for 2019–20 (compared to a previous expectation of six per cent fall). This compares to ANZ Research’s expectations of a 5.5 per cent increase in the terms of trade in 2018–19 and a 2.6 per cent fall in 2019–20.

Consequently, ANZ Research sees stronger nominal GDP growth of 5.3 per cent in 2019–20 compared to Treasury’s 3.6 per cent.

Treasury estimates year-average real GDP growth of 2.75 per cent in 2019–20, revised down from a three per cent forecast at MYEFO in December 2018. In ANZ Research’s view, real GDP in 2019–20 will be weaker at 2.2 per cent (year-average).

Treasury’s employment growth forecast of 2.1 per cent through the year to June quarter 2020 is a touch stronger than our 1.8 per cent. Treasury’s wage forecast for 2019–20, which ANZ Research has long-thought too strong, was revised down to 2.75 per cent from three per cent, between MYEFO and Budget. It is still stronger than ANZ’s forecast of 2.3 per cent, however.

Capital spending was revised up in the Budget compared to MYEFO, by $A9 billion over the 2018–19 to 2021–22 years. Around $A6 billion of this was due to higher capital grants to the states and territories, with financial asset investments up by a net $A3 million. The profile of government capital spending is still expected to fall as a share of GDP over the coming four years despite the increases.

An increase in the value of Australian Government Securities due to lower yields than were assumed at the time of MYEFO, increases net debt in the 2019–20 financial year to 19.2 per cent of GDP (the previous projected peak was 18.5 per cent of GDP in 2017–18). But thereafter, with a mild improvement in the underlying cash balance over the coming four years, net debt as a share of GDP is expected to fall to 14.4 per cent of GDP by 2022–23.

The Government’s projections have an elimination of net debt by 2029–30.

With the Parliamentary Budget Office highlighting the drawbacks of the net debt measure as an indicator of fiscal sustainability, we also consider net financial worth. There has been a widened gap between net debt and net financial worth in recent years, but a projected recovery in this measure also, to -19.7 per cent of GDP by 2022–23.

The alternative budget

With the election looming and the opposition Australian Labor Party ahead in the polls, the alternative budget will be worth examining closely.This Budget shapes the outlook for an ALP Government’s fiscal agenda. We know that an ALP budget would have $1 billion more for low income earners straight away but tax cuts for mid-high income earners would be cancelled.

Other key ALP policies would limit the tax benefits for new property investors who claim losses on their property income from established dwellings and lowers the capital gains tax discount from 1 January 2020. Tax refunds for share investors who do not pay tax would also be eliminated.

The ALP has said it would issue a mini-budget in the third quarter of this year if it were to win office.

CEDA Members contribute to our collective impact by engaging in conversations that are crucial to achieving long-term prosperity for all Australians. Find out more about becoming a member or getting involved in our work today.