Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

06/09/2024

The 2024 NAPLAN results released last month have left many with a strong sense of disquiet.

The data show one in three school students is falling short of benchmarks on numeracy and literacy. More than one in 10 students were flagged as needing additional support.

Australia’s lacklustre performance in education, as highlighted by these results and the disappointing Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores, is a focus of intense public debate. But it is a complex, multi-faceted issue, influenced by a range of factors spanning from funding arrangements to entrenched social disadvantage.

CEDA looked at Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey data on one of the key inputs into academic success – educators.

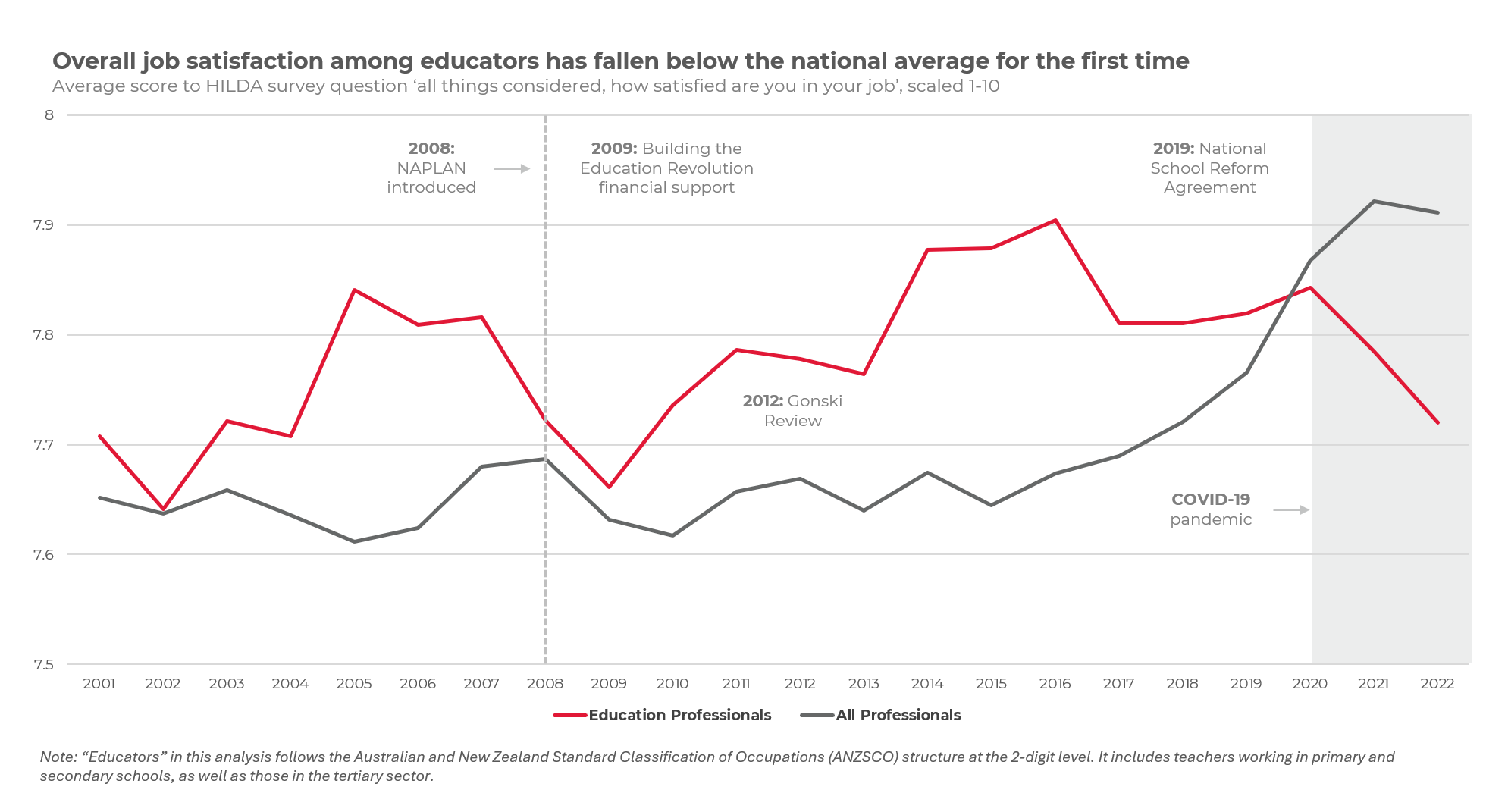

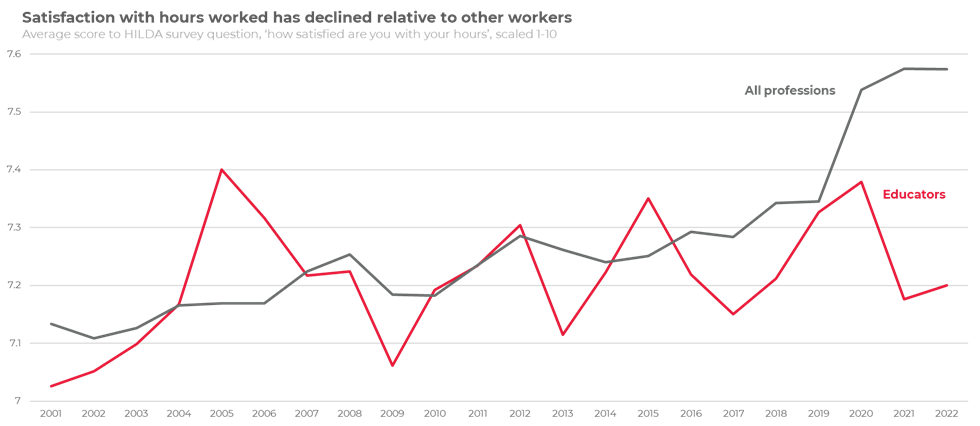

We examined survey responses about how satisfied those working in the education sector were with their hours, the work itself and their job overall, comparing these to national averages of job satisfaction for other professionals. In the HILDA survey, “education professionals” includes teachers working in primary and secondary schools, as well as those in the tertiary sector. They reported worsening satisfaction across all measures.

While previously educators had reported a higher level of job satisfaction relative to others, recent years have seen a reversal of this trend.

A sustained fall in job satisfaction from 2015 onwards, which accelerated following the COVID-19 pandemic, aligns with anecdotal evidence of the challenges of teaching during this period.

While satisfaction with hours worked previously kept pace with the economy-wide average, here too we observe a recent divergence. The shift to working from home and increased flexibility available to workers in many professions during the pandemic but less so for teachers, could have had an impact on this measure, though there are recent signs of a slight improvement.

These faltering levels of satisfaction may also be contributing to a falling supply of teachers. Data from Jobs and Skills Australia shows that in the past year alone, the number of primary school teachers has fallen by five per cent.

Concerningly (but unsurprisingly), falling teacher numbers are concentrated in regional communities. For example, over the past five years, the number of primary school teachers in outback Queensland and South Australia has fallen by 11 per cent and 13 per cent respectively. The five-year decline in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley is an alarming 27 per cent.

These figures correspond with a recent survey by Monash University, which identified that just three in 10 educators in the public school system anticipated remaining in public schools for the remainder of their career.

When exploring the drivers behind this, excessive workloads, concerns around pay and a lack of respect for the career were highlighted as factors causing some to consider leaving their roles. Other drivers included poor behaviour from parents, administrative burden and even student violence.

These trends are not unique to Australia. New analysis published by the United States’ National Bureau of Economic Research presents a profession in crisis, with public perceptions about careers in education at 50-year lows.

Asked whether they would like their children to become teachers, just over a third of parents surveyed expressed their support for the profession. The proportion of first-year college students intending to pursue teaching was below five per cent. Levels of interest in teaching among high school seniors were even lower. For those already in the career, longitudinal data show plummeting levels of satisfaction.

The trends playing out in NAPLAN, PISA, HILDA and other survey data are highly troubling. The structural shifts underway in our economy continue to make clear the need for cultivating robust foundation skills such as literacy and numeracy. Teachers are critical to this process.

The recent NAPLAN results will surely invite scrutiny to the policy settings in the education sector, presenting an opportunity to highlight and address the challenges our educators face and give them the support they need to succeed.

Getting these settings right is essential to help the education sector develop the next generation of talent.