PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

13/09/2017

The global economy is improving, but its politics is worsening. An erratic President Trump, an aggressive North Korea and renewed acts of terrorism are spooking the public, but not yet share markets.

But daily news can distract us from the big picture. So here I shall examine the most positive and negative arguments for the future of the global economy because they help identify opportunities and threats that short term analysts overlook.

Future perfect

Starting with the optimists, here are three reasons why they think the future is an economic nirvana.

Disruption

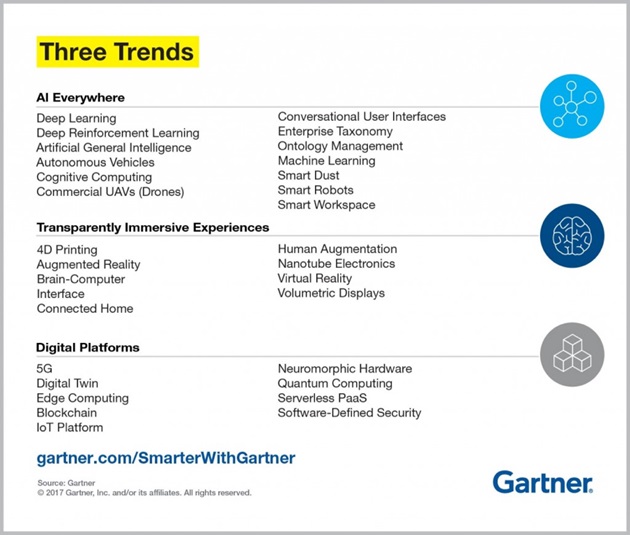

Technological breakthroughs are creating new products and services that will unleash consumer demand, boost productivity and prosperity for all. Here is a list of what is in the pipeline.

Figure1:

According to Gartner Inc, these developments comprise three distinct technology trends that will give companies competitive advantage; “the perceptual smart machine age, transparently immersive experiences and the digital platform revolution”. The first is about harnessing data to solve problems, the second about making technology more human centric and the third is about marketing and delivering services online. Examples of each are shown below.

Figure 2:

Sceptics of the new technology revolution point to only a fraction of new inventions succeeding after expectations peak in the “The Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies” chart shown above.

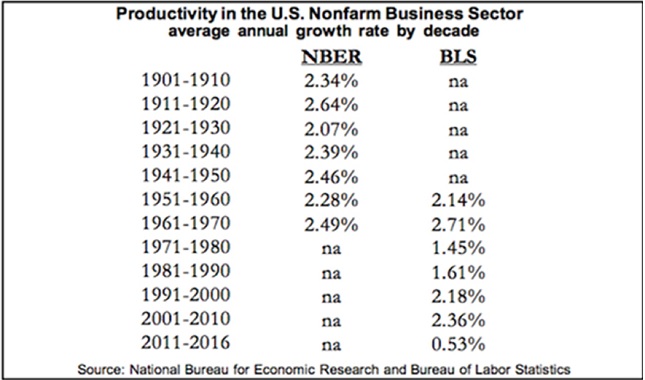

Also Robert Gordon, author of The Rise and Fall of American Growth, says the post 1970 information revolution has been accompanied by a fall in productivity improvement. See next chart for the US, the home of Silicon Valley innovations.

Figure 3:

Nevertheless, a new age of innovation is the best hope for shaking mature economies out of their present torpor. Harry Dent, the cycle theorist, reckons that innovation happens in 45 year cycles and that the last upsurge ended in 2008 so the next won’t commence until 2032. In the meantime, lots of breakthroughs will happen, but they won’t reach commercial scale. Or they will be refinements of existing technology with only incremental benefits.

But Peter Diamandis and Steven Kotler, authors of Abundance: Why the Future Will Be Much Better Than You Think, strongly disagree:

“We are now entering a period of radical transformation. Progress in artificial intelligence, robotics, infinite computing, ubiquitous broadband networks, digital manufacturing, nanomaterials, synthetic-biology and many other breakthrough technologies will let us make greater gains in the next two decades than we’ve made in the previous 200 years. We will soon have the ability to meet and exceed the basic needs of every man, woman, and child on the planet. Abundance for all is within our grasp.”

Development

China’s One Belt/One Road initiative will join up 60 countries of Asia Pacific, Central Asia and Eastern Europe via vast transport infrastructure corridors. By linking Asia to Europe, China envisages a new Eurasia that will overshadow America and drive future world growth.Figure 4:

As can be seen in the chart below, Asia has already grown from 16 per cent of world GDP in 1960, to 45 per cent now. South America and Africa also have enormous potential once they get their governance in order.

Figure 5:

Jeff Shubert, the former head of the International Centre for Eurasian Research in Russia says, “The idea of Greater Eurasia is a fantasy” because “China seems in no hurry to change present circumstances and trends in central Eurasia because it has the upper hand…”

Whether China’s Eurasian dream is realised or not, its middle class is set to expand by a massive 850 million between 2009 and 2030 while that of North America and EuropeSstagnates. By 2030, China should account for 22 per cent of global middle-class spending; three times more than the US.

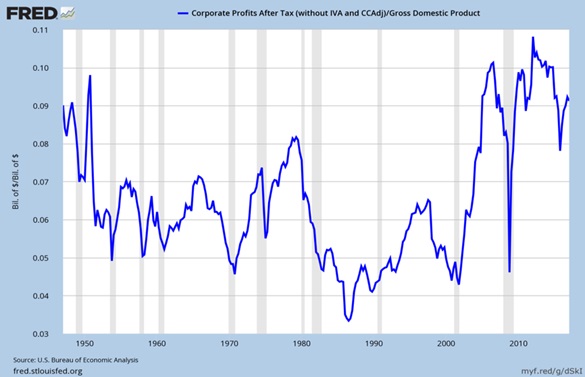

Drawbridges

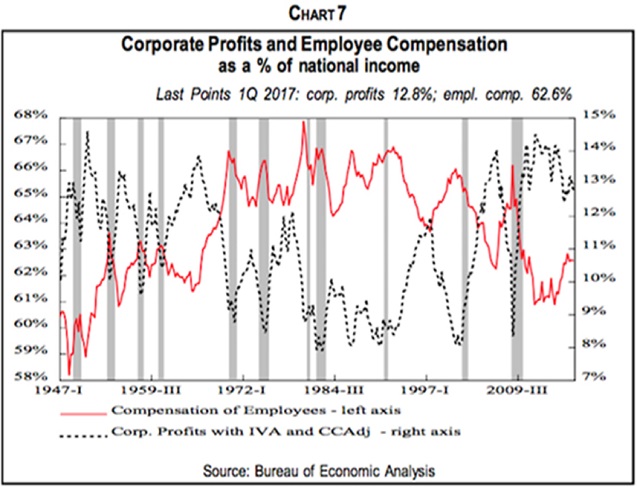

Growing barriers to trade and an increasing concentration of industry are preventing deflation and securing a higher share of GDP for profits as can be seen in the chart below.

Figure 6:

Though much is made of new start-ups, the truth is that mergers and acquisitions are reducing industry competition. According to a recent academic study:

More than 75 per cent of US industries have experienced an increase in concentration levels over the last two decades. Firms in industries with the largest increases in product market concentration have enjoyed higher profit margins, positive abnormal stock returns, and more profitable M&A deals, suggesting that market power is becoming an important source of value. Lax enforcement of antitrust regulations and increasing technological barriers to entry appear to be important factors behind this trend.

Also, a popular backlash against globalisation has given the upper hand to politicians advocating greater trade protection. Donald Trump’s scrapping of the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) signalled that capitalist America would no longer champion free trade, leaving it to communist China’s President Xi to espouse free markets to the world Economic Forum in Davos.

A lessening of competition is bad for consumers and productivity, but comforting to many industries (and investors).

Alan Kohler, publisher of The Constant Investor, wrote recently:

The overriding goal of big companies is to hang on to what they’ve got and if possible become a monopoly, so they can move from having to earn profits to the collection of risk-free rents.

Small businesses can’t get bank loans because banks prefer the security of property mortgages. Big businesses simply bypass banks by issuing their own debt securities. Many prefer mergers and acquisitions over organic growth.

For investors, oligopolies are like castles with drawbridges that keep out marauders. The half a dozen largest listed companies in America are Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon and Facebook. Except for Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, each of these firms has created a niche market that it dominates. And Warren Buffet likes investing in them.

In Australia, our six-pack consists of the CBA, Westpac, ANZ, NAB, BHP Billiton and CSL. According to former Federal Treasurer, Peter Costello, Australian big banks are a “quadropoly” thanks to government deposit guarantees and protection from mergers and takeovers. The public loathes banks, but it prefers stability to cutthroat competition when it comes to our financial system. And investors do too.

Future bleak

The contrary view is held by the pessimists. Three reasons why they think the economy is doomed are:

Debt

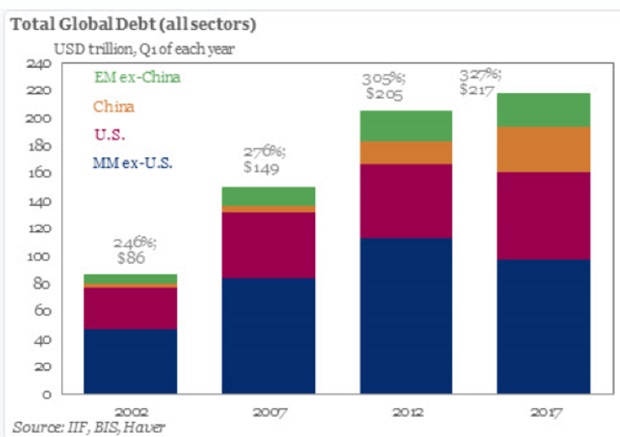

The world is drowning in record debt and when deleveraging begins it will be a drag on consumer, government and business spending.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 was triggered by excessive asset speculation and inadequate financial regulation. It left a mountain of debt, which instead of being pared back, has grown bigger as shown in the chart below. Because central banks have reduced interest rates to historic lows, servicing the increased debt has been manageable.

Figure 7:

But when rates return to normal, it will trigger massive loan defaults. That could precipitate an economic depression and financial meltdown, especially given moves in America to loosen banking oversight rather than tighten it.

The contrary view is that over a third of global bonds are owned by central banks that could be expunged by legislation. In other words, one arm of government (the Finance or Treasury Department) owes money to another arm (a Central Bank) that could be forced to forgive it. That is possible, but the remaining bonds held by the private sector could not be extinguished without debasing the currency, as happened in Germany after World War I.

Globally, the bond market is much bigger than the share market so scrapping much of its scrip could shatter confidence in the financial system.

James Rickards, author of The Road to Ruin, thinks the world’s huge debt overhang will see a collapse of the global financial system and hyperinflation. Only time will tell.

Demography

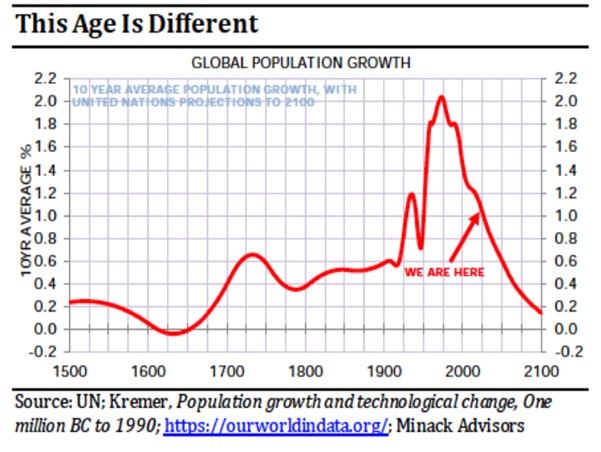

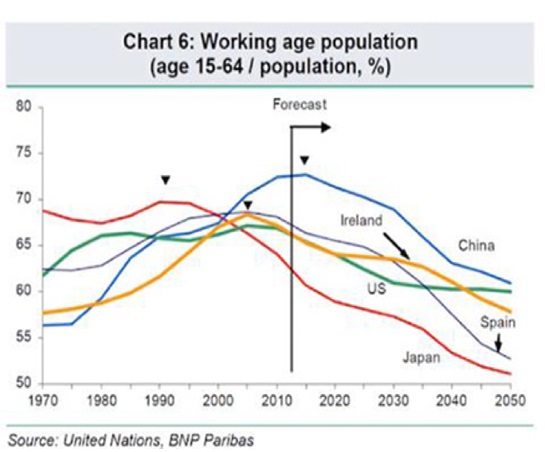

The world’s population is ageing and its workforce participation is falling. Older people save more and spend less and fewer workers detract from economic growth.

Note in the next chart how population growth accelerated in the 19th and 20th centuries, but is reversing in the 21st century.

Figure 8:

In most developed and developing countries, the working age population as a share of the total population is falling as shown in the chart below. There will be fewer people to support those who are retired, disabled, unemployed or otherwise not working.

Figure 9:

Optimists believe robots will fill this gap, but machines aren’t paid wages nor do they pay taxes. That could reduce funding for private consumption and government services.

Countries with a shrinking workforce can always turn to immigration. For instance, Angela Merkel accepted a million Syrian refugees not just for humanitarian reasons but to fill a German labour shortage.

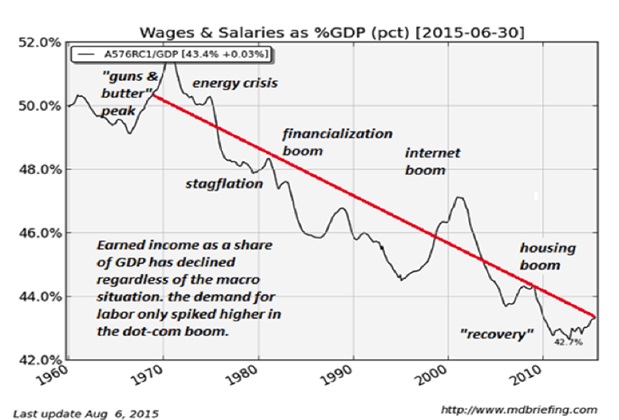

Distribution

The increased concentration of income and wealth is boosting savings, but pushing ordinary people into unstainable debt to maintain living standards.

In America, total wages and salaries have fallen from over 50 per cent of GDP in the 1960s, to 43 per cent now.

Figure 10:

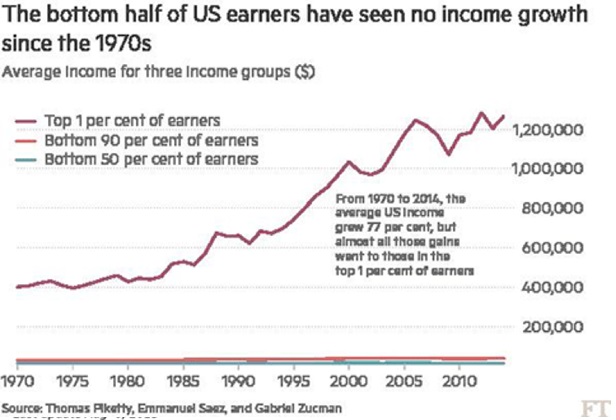

Since 1970, the average US income increased by 77 per cent in real terms, but almost all those gains went to the top one per cent of earners, as shown below.

Figure 11:

Both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders appealed to white voters who felt they had been cheated of the American Dream. Yet, according to the Pew Research Centre, that Dream is still strong with Hispanic and Black minorities, even though they comprise most of America’s underclass.

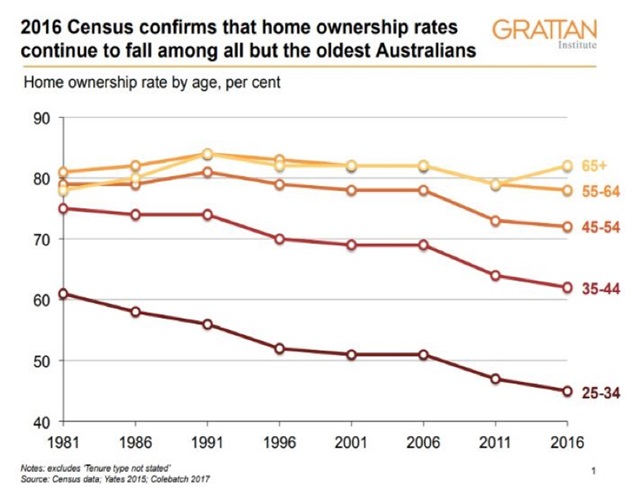

In Australia inequality (except for Indigenous Australians) is intergenerational rather interracial. Baby boomers (those born between 1945 and 1964) are by and large well-endowed, having bought housing when it was cheap and having enjoyed a recovery in superannuation assets following the GFC. Younger generations either can’t afford to buy a home, or if they already own one, face mortgage stress should interest rates rise. As a consequence home ownership is falling as shown below.

Figure 12:

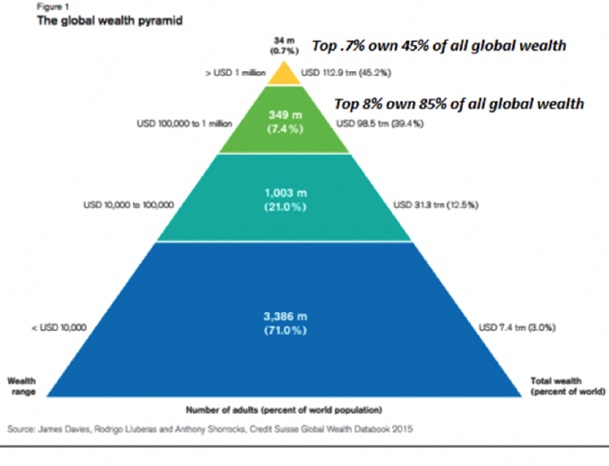

Globally, almost half of all wealth is owned by less than one per cent of adults, with the top eight per cent controlling 85 per cent of assets. Those on the left of politics say inequality has reached a tipping point that will invite drastic income and wealth redistribution.

Figure 13:

On the political right, ultra-nationalists want to block immigration, imports and foreign investment. Neo-liberals are on the defensive because the high share of profits to GDP is no longer associated with general prosperity as it was before the GFC and in the 1950s.

Figure 14:

With big business out of favour, younger voters are swinging to the left and older voters to the right. Take television ratings in America. MSNBC, which supported socialist Bernie Sanders, and Fox News, which backed and continues to back nationalist Donald Trump – each attract more viewers than CNN, which prides itself on factual news and political neutrality (notwithstanding Trump’s hostility to it).

The paradigm shift from neoliberalism to either socialism or nationalism could mean a more hostile investment environment.

The contrary view is that while inequality might be growing within rich countries, it has shrunk between nations because globalisation is enabling poorer countries to export themselves out of misery. Developing countries see free trade, migration and capital flows as making the world more equal and productive. By contrast, developed countries are feeling internal political pressure to close their borders to foreigners and foreign produce.

The growth opportunities are clearly in emerging and frontier markets or companies listed in developed markets that export to, or invest in, those countries – most of which are in Asia.

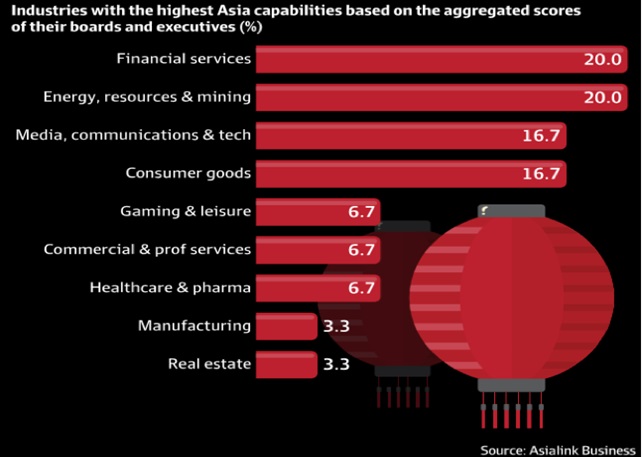

Unfortunately Australia’s top listed and unlisted companies rank lowly on their Asian capability according to a new study by Asialink called Match Fit: Shaping Asia Capable Leaders.

For investors wanting to back local companies with an Asian focus, these findings suggest financial services, energy, resources and mining with a score of 20 out of 30 rate best (see chart below).

Figure 15:

Conclusion

Frankly, I don’t know who will prove right, the optimists or the pessimists. My guess is that there are positive and negative forces that each side has overlooked. Though, to be fair, I have not covered all the possibilities here. Also, the world tends to muddle through problems fixing crisis with solutions that sow the seeds of the next crisis.

For instance, the GFC was not a rerun of the 1930s Great Depression because central banks printed money to shore up bank liquidity and fund government spending. This did not spark hyperinflation, except for asset prices that were stoked by ultralow interest rates.