PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

30/09/2024

CEDA Head of Research Andrew Barker gave a guest lecture to Deakin MBA Economic Environment students on CEDA’s work on clean energy jobs and precincts, as well as what Australia can learn from Denmark’s emissions reductions.

I'll start with some analysis from the OECD, because I think it's always good to learn from the examples of other countries.

This was a report that I worked on in 2021, which was an economic survey with a very strong focus on climate policy in Denmark.

It’s a good example that I think Australia and other OECD countries can learn from about successfully cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

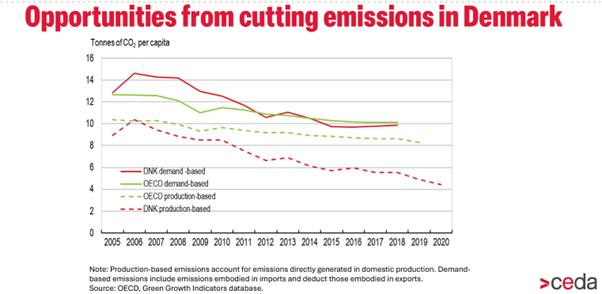

This chart here is showing two different measures for greenhouse gas emissions.

One of them is production-based, which is the normal way in which you measure greenhouse gas emissions as it's reported to the UNFCCC process, and that's based on the greenhouse gases that are that are emitted within the country from predominantly burning fossil fuels.

That's the normal measure of greenhouse gas emissions from a country but there's another way that it is also measured in OECD statistics, which is a demand-based measure.

If you take all the goods and services that are being consumed in Denmark, or any other OECD country for that matter, and you look at where they came from and the emissions associated with creating those goods and services, what would the total emissions of that country look like then?

And you can see in the case of Denmark, that demand-based emissions are higher than production-based emissions, and that's because Denmark has higher emissions in the goods that it imports than it does in the goods and services that it exports.

It's an importer of emissions-intensive goods like steel, aluminium and cars, for example.

But what's interesting here is the time profile.

You look at the normal production-based measure of greenhouse gas emissions and you can see that that's been on a constant decline since 2006.

The demand-based measure of emissions has also been in decline since 2006.

Denmark has more than halved its greenhouse gas emissions already, but it hasn't just been a matter of doing that by exporting the emissions overseas, by importing a whole bunch of emissions-intensive goods.

Rather, there's actually been real cuts in the total amounts of emissions associated with goods and services consumed in Denmark.

The way that that was done was predominantly by decarbonising the electricity sector, which was a very coal-based electricity sector historically.

That shifted to renewables, particularly wind, including offshore wind, and what this success in cutting emissions didn't do was it didn't derail the economy.

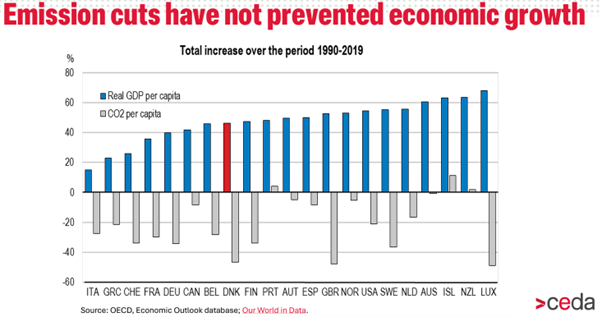

You can see these grey bars of cuts in carbon dioxide emissions per capita almost halving.

This is only up to 2019, so if you had the latest data here that would have more than halved carbon dioxide emissions per capita.

Yet at the same time, real GDP per capita continued to grow, employment continued to grow, there weren't big outbreaks of unemployment and you can see a lot of other OECD countries have also had a lot of success in cutting emissions without derailing their economy.

Australia is the fourth from the right, so there has been quite strong growth in GDP per capita over that period, particularly during the 1990s when we had a real productivity boom.

But because these emissions data exclude land use, land use change and forestry, which is where Australia has reduced emissions a lot, there's actually very little change in Australia's greenhouse gas emissions over this period, so there's still a lot of work to be done.

In terms of what Australia can draw from the experience in Denmark as a developed country that's been successful in really cutting its greenhouse gas emissions a lot – what that showed was that policy was able to bring on low emissions technologies and indeed reduce the costs of those low-emissions technologies.

We saw offshore wind, for example, really come down the cost curve as deployment increased and innovation and technology improved.

What was required to do that was consistent and complementary support.

There were clear targets set and subsidies for deployment, but also, cutting greenhouse gas emissions is not about just one market failure, there's many market failures involved.

It's not just about paying subsidies for clean energy, it's also around innovation, the need to develop new clean energy technologies, so research and development funding was really important there.

Certainly, as a share of GDP, Denmark's been putting a lot more money into research and development of clean energy than Australia and the International Energy Agency has clear data on that.

But they’ve also been making sure there aren't other barriers, with a very streamlined planning system.

There’s data where it took about 16 months to get the permits through for an offshore wind farm in Denmark, but it took about twice as long as that in Germany.

Not surprisingly, a lot more offshore wind development happened in Denmark and when you speak to people in Australia, they say, if we can match Germany, that will be pretty good at the rate we're going.

As I mentioned, innovation was really important along with the delivery of new technologies, and one really good example is around offshore wind, and indeed the manufacture of the wind turbines.

Denmark, by supporting its own industry, was able to develop a turbine manufacturing industry.

That actually became a really highly technological industry where there's real benefits from getting the aerodynamics right and constructing them really well – it's almost aeronautical type technology to really build these wind turbines properly.

There's some other OECD work that showed how Danish companies developed a competitive advantage and that enabled them to build a new export opportunity.

There are a lot of exports of manufactured wind turbines from Denmark, so they created export opportunities around clean energy, so that's worth learning from.

Also, as Denmark's gone to basically 100 per cent renewables, they have managed to maintain security of electricity supply.

That's really important and you can't just change to renewables that rely on the wind blowing and the sun shining without thinking pretty seriously about how you're going to ensure security.

But Denmark showed they were able to do it.

They had an advantage we don't have in that they were linked to the Nordic electricity system and Norway and Sweden have a lot of hydroelectricity.

That was something they were able to draw on, almost like a battery.

For us in Australia, we need to be more explicit about what the storage and the long-term storage options we have are.

Should that be pumped hydro, should that be batteries, and trying to get that mix right is difficult, but Denmark proves that it's possible to overcome that with access to the right technologies.