Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Governments should apply a consistent framework when backing clean energy projects,

to ensure support goes to those with the best chance of success.

“Innovation precincts” cluster businesses, industrial facilities, education providers and manufacturers together. They have been shown to help catalyse investment, job creation, collaboration, exports and innovation.

Establishing “clean energy precincts” that bring together businesses, institutions and organisations working towards a low-or-no emissions future can help seize our clean energy export opportunities.

Federal and state governments are already planning to spend $8.3bn in funding for hydrogen development alone, much of which will support precincts.

The large amount of money involved means it is critical that resources are used effectively.

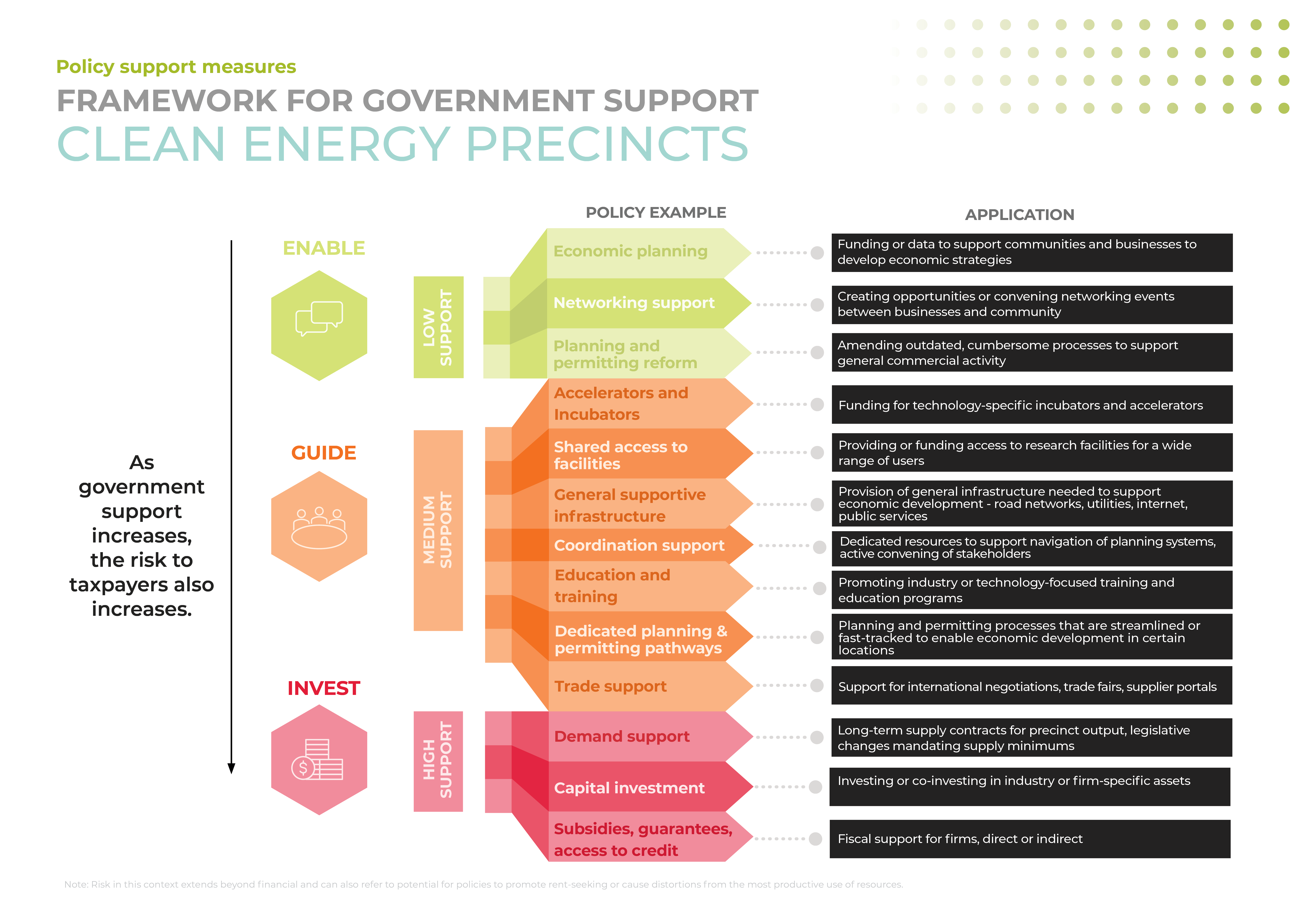

This report proposes a simple framework to prioritise government support for clean energy precincts. We classify this support into three categories:

Policies that enable the conditions for private investment in precincts;

Those that guide towards specific technological or economic outcomes; and

Those where governments invest directly in precincts.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

IMPLEMENT FRAMEWORK FOR GOVERNMENT SUPPORT

Apply a consistent framework to government support for clean energy precincts, recognising that public investment in commercial projects requires deeper independent analysis of market opportunities than enabling or guiding development through coordination, provision of shared infrastructure, better planning and community engagement.

Recommendation 2

CLEAR PURPOSE FOR CLEAN ENERGY PRECINCTS

Ensure all clean energy precinct proposals have a clearly articulated purpose, with time-bound, measurable objectives that enable transparency, monitoring and evaluation. Ongoing financial support should be explicitly linked to meeting these objectives.

Recommendation 3

APPOINT COORDINATION BODY

Precinct proponents should appoint a coordination body. Coordination needs to be based on a shared understanding of precinct purpose, collaboration, alignment of interests and clear allocation of responsibilities.

Recommendation 4

ENGAGE WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Government and industry should engage deeply and early with local communities to assess local barriers and opportunities and build social licence.

Recommendation 5

REFORM PLANNING AND PERMITTING

Cooperation across levels and departments of government is needed to update and simplify planning for clean energy precincts, while maintaining environmental and community protection.

i. Governments should create single points of contact or lead agencies for permitting of precincts.

ii. Governments may need to take a more active role in supporting approvals, particularly in areas where they have greater expertise and multiple parties are looking to develop a precinct.

Executive Summary

Australia has many natural advantages in the transition to net-zero emissions. We have harnessed sun and wind to reduce emissions domestically. But we can make a much bigger contribution to the global transition by using these advantages, as well as our abundant land and critical minerals, to export clean energy and green hydrogen, iron, aluminium or ammonia.

As countries around the world pour billions of dollars into their own transitions, we must seize these export opportunities.

Establishing “clean energy precincts” that bring together businesses, institutions and organisations working towards a low-or-no emissions future can help.

“Innovation precincts” cluster businesses, industrial facilities, education providers and manufacturers together. They have been shown to help catalyse investment, job creation, collaboration, exports and innovation.

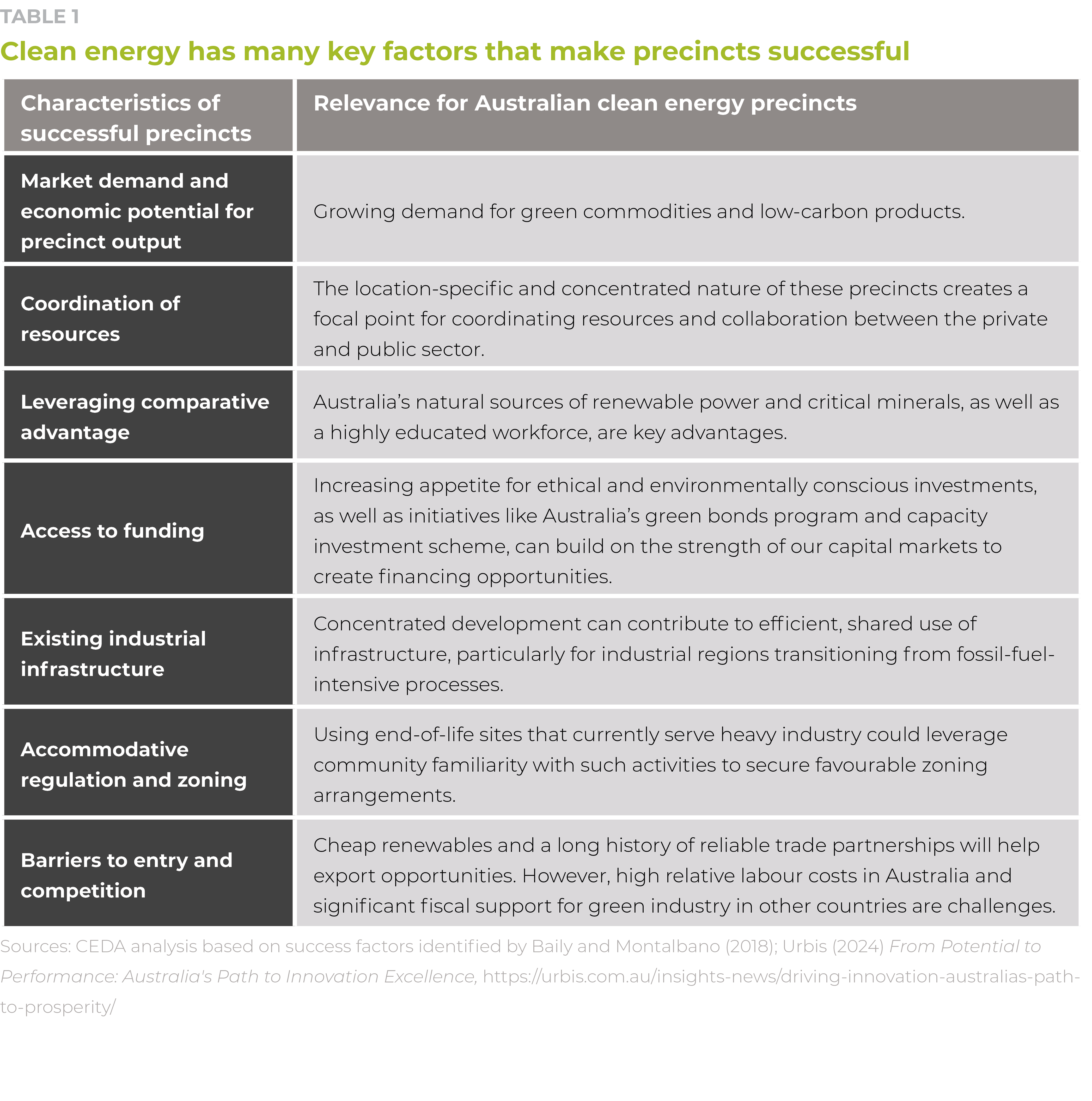

In Australia, clean energy shares many of the key characteristics of successful innovation precincts in a range of industries overseas, including strong local comparative advantages.

Shared use of energy infrastructure, pooling of skilled workers and access to low-cost renewable energy offer substantial advantages to developing clean energy opportunities in precincts. There is also potential to leverage existing infrastructure and skills to support communities and jobs in regions that are transitioning away from fossil-fuel-related industries.

Australia has opportunities for several large, industrial-scale clean energy hubs across all states and the Northern Territory. Federal and state governments are already on board, with $8.3 billion in funding for hydrogen development alone, much of which will support precincts.

This funding is fragmented, however, with more than 30 federal and 50 state and territory programs providing hydrogen-specific support. The large amount of money involved means it is critical that resources are used effectively and precincts are set up for success. Governments cannot support every project proposal, with discipline needed to ensure support does not go to proposals that are unlikely to stack up economically.

At the same time, complex, fragmented and in some cases outdated planning and permitting processes are delaying progress, creating a barrier to development without delivering better environmental or community outcomes. The need to engage with many different agencies on complex precinct developments slows progress and makes it hard for proponents to know what each agency is responsible for.

Early, deep and active consultation will be essential not just to ensure the community is on board, but also to avoid developments that do not align with local strengths. Rather than supporting social licence, however, current planning and permitting systems can undermine it through fragmented requirements and repetitive consultation over minor changes.

This report proposes a simple framework to prioritise government support for clean energy precincts. We classify this support into three categories:

- Policies that enable the conditions for private investment in precincts;

- Those that guide towards specific technological or economic outcomes; and

- Those where governments invest directly in precincts.

All levels of government have important roles to play to enable and guide clean energy precincts. While private businesses may in some cases be able to seize commercial opportunities and take the lead in precinct development, governments are better placed to provide coordination, reforms to planning and shared infrastructure.

But governments are already going further and investing in specific precincts.

Government investment transfers or shares risk rather than removing it. The public needs to share in the benefits as well as the costs of support, so that the upsides of successful projects can offset the downsides of inevitable failures.

In such cases, clear objectives are necessary to underpin good governance and provide the best chance of success via:

Deeper independent analysis of market opportunities by a body such as the Net Zero Economy Agency or Australian Renewable Energy Agency, to ensure the local area has a sustainable comparative advantage;

A focus on innovation and emerging technologies, where social benefits and risks for private businesses are likely to be largest;

Consolidation of the large number of funding programs available, to better coordinate support and make sure it flows to the best projects; and

Regular evaluation and updating of policies, allowing for the possibility of failure.

Around the world, governments have announced more than $US1.3 trillion worth of clean energy subsidies since 2020. The Federal Government rightly points out that “we don’t have to go dollar-for-dollar in our spending” compared with other nations, “but we can go toe-to-toe on the quality and impact of our policies.”

The scale of support for clean energy internationally creates opportunities for Australian clean energy precincts, but also increases the risk that we will not be able to compete if we choose the wrong projects or technologies. We need to remove barriers to development, engage communities and enable the best projects.

This requires an overarching framework to better target how and where governments support precincts.

Innovation precincts (sometimes called clusters or hubs) bring together businesses, higher education and research institutions, as well as other public and private entities, to encourage collaboration on complementary economic activities.

They offer cost efficiencies through sharing of infrastructure and facilities. They also attract and develop a pool of skilled workers who can share knowledge. As the knowledge, capabilities and networks within the precinct develop, innovation, increased competitiveness and higher productivity can follow. International experience has shown this encourages investment, boosts wages and attracts yet more skilled workers, establishing a positive feedback loop.

While innovation precincts can be newly built, clean energy precincts in existing industrial sites have potential to gain greater commercial advantage by leveraging existing infrastructure and zoning at end-of-life carbon-intensive industrial facilities.

Clean energy precincts also offer additional benefits unique to the net-zero transition. Shared use of large-scale infrastructure helps to offset the resource intensity of reducing emissions in the energy sector. Proximity between energy producers and heavy industry users can provide access to low-cost renewable energy, minimise efficiency losses from distant transmission, and in some cases support energy demand management and circular economy practices.

Having research institutions and education providers nearby supports commercialisation of research and helps cultivate a pipeline of workers equipped with the skills demanded by industry.

The Tonsley Innovation District in South Australia shows how well-executed precinct policy can support economic transition in Australia.

Situated on the former Mitsubishi Motors production facility, the district was born from a period of significant economic dislocation in South Australia.

As Mitsubishi closed its operations in 2008, there was much anxiety within the community about what the closure would mean for its 1000 workers.

The State Government purchased the site in 2010, and in the years since it has grown into a hub of economic activity, with 2000 workers, 8500 students, a network of local and global businesses, and campuses for Flinders University and TAFE SA.

Tonsley’s transformation was not achieved overnight, and success was the result of concerted efforts by a number of motivated stakeholders.

Initially a shared project between the state’s economic development agency and the state’s urban renewal organisation, RenewalSA, it became clear early in the project that development would be better served by a single body, with the task falling to RenewalSA.

Central to guiding the direction of the precinct has been strong engagement between RenewalSA and the Tonsley community. This enabled leaders at RenewalSA to foster networking and collaboration among tenants, guide proponents toward relevant government support, build a shared sense of identity and deliver a framework for organic growth.

Co-locating Flinders University and TAFE SA onsite was also important to create a community and culture of innovation and knowledge spillovers. The presence of these institutions has strengthened the relationship between commercial tenants and educators, helping to cultivate skills development for in-demand areas. For example, BAE Systems and SAGE Automation run robotics workshops for students studying in the district.

While looking to future industries is part of the fabric of Tonsley, leaning into existing local strengths has been crucial. For example, X-ray technology company Micro-X saw value in employing former automotive workers who understood lean manufacturing processes as it set up its operations in the district.

Beyond job creation and economic revitalisation, the precinct’s success will enable it to repay the investment provided by the state government in the coming years.

Clean energy precincts: How to seize the green export opportunity

All participants need to play a role

The success of a precinct depends on government, industry, education and the community acting collaboratively toward a shared goal. This is particularly true for clean energy precincts, which are also technically complex, have large capital requirements and bring environmental risks as well as opportunities.

Collaboration and a clearly articulated purpose are particularly important given the long lead time before a project reaches maturity. There should be metrics for success attached to relevant stages of the project life cycle. Clarity on these objectives should promote accountability between stakeholders and support robust forward-planning, investment decisions and management of community expectations.

Summary of key roles in clean energy precincts

Community must be at the forefront

Clean energy precincts are more than just the wires, concrete and steel that channel renewable energy and produce green exports. The communities they exist in provide the land and skills needed. Meaningful engagement and collaboration with communities is thus critical for both their social and economic success.

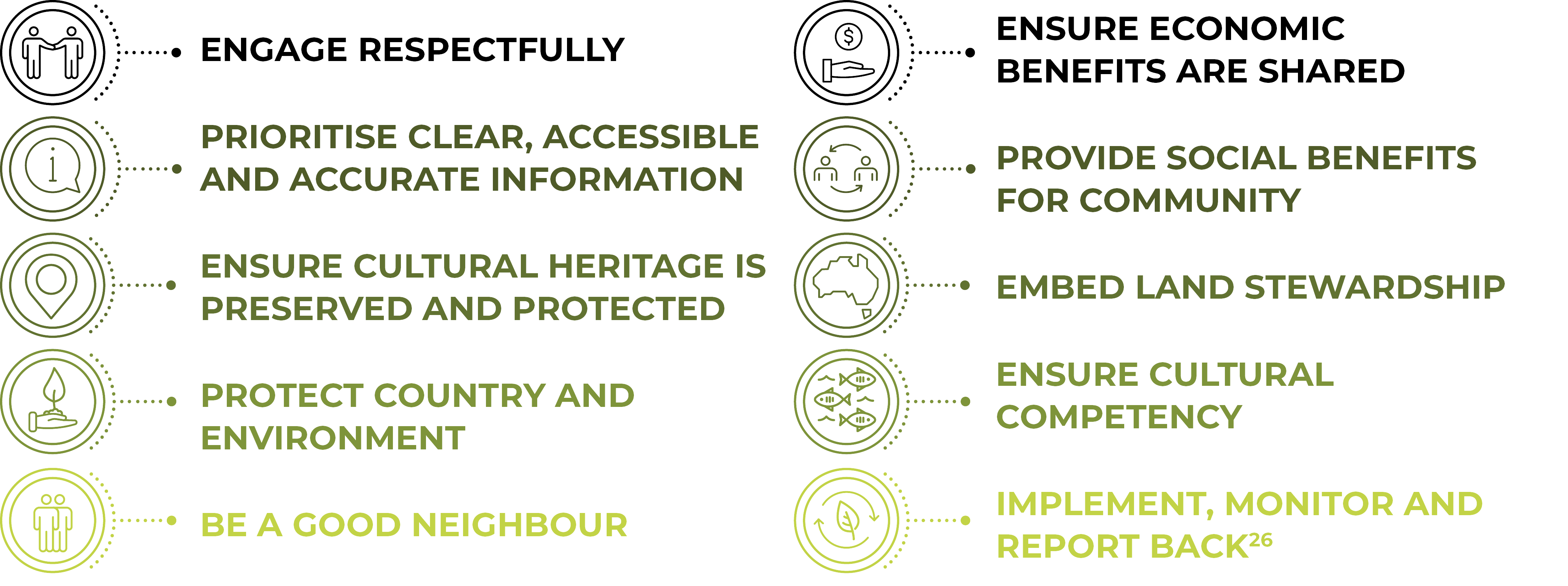

Economically sustainable transformations must start with a strong understanding of community needs, strengths and obstacles. While this is a prerequisite for achieving an enduring social licence, a bottom-up approach can also help proponents tap into local comparative advantages and networks. Effective, robust consultation between community members and industry can help identify the best ways for policy to support developing precincts. This approach is summarised in the Community engagement tree below, which has been developed through CEDA’s broad consultation with potential precinct stakeholders.

Respectful, genuine and ongoing engagement with First Nations community members must be prioritised as these precincts are developed. New ventures need to provide for genuine participation and empowerment of First Nations communities, which can de-risk projects through leveraging local knowledge and integrating native title approvals within project development activities.

An example is the East Kimberley Clean Energy Project, a green hydrogen and ammonia project for local use and export where the traditional owners of the land will be joint shareholders in the project development process.

The Federal Government is currently preparing the First Nations Clean Energy Strategy, which will provide a platform for Indigenous communities to help shape Australia’s energy transition strategy and identify best practice methods of consultation. Existing work from the First Nations Clean Energy Network (2022) identifies the following best practice principles for clean energy projects:

Governments can enable precincts

Research consistently finds that all levels of government play an important role in facilitating innovation precincts and supporting collaboration. Benefits documented above from sharing of infrastructure, knowledge and skill spillovers enhance the potential for government support of precincts to offer greater benefits than support for individual projects. Government involvement can also create greater alignment and understanding of regulatory barriers to development and how these can be addressed.

But these roles need to be tailored to their strengths and complement those of other participants. Some key roles for governments in clean-energy precincts are:

Coordination: As set out above, coordination of resources is an important factor in the success of innovation precincts. Governments do not necessarily need to be the primary coordinator, but can bring participants together and enable strategic planning. Coordination of community engagement can avoid disjointed and repetitive consultation on a project-by-project basis.

Capturing spillover benefits from innovation and skills: In a well-functioning precinct, benefits from research, knowledge and skills accrue beyond individual firms. These broader benefits mean there can be a role for government to drive or incentivise collaboration, for example across industry, universities and communities. Due to greater novelty, knowledge spillovers have been estimated to be 60 per cent greater for clean than high-emissions technologies.

Providing shared-use infrastructure: Governments can make catalytic infrastructure investments that benefit from big economies of scale, supporting progress where individual firms would not reap enough benefit to invest at an efficient scale.

Supporting a pipeline of skills: There is already a shortage of clean energy skills. Governments must help workers to gain new skills and help people to transition from fossil-fuel energy jobs.

Fit-for-purpose planning and permitting: Cumbersome permitting processes can slow or stop precinct development. In Barcelona, Spain, cooperation across all three levels of government was needed to overhaul outdated regulations to enable innovation districts. Equally, important environmental and community concerns must be dealt with properly.

Australian planning processes are often highly complex, involving many agencies (Case studies 3 and 4). Governments may need to take a more active role in supporting approvals, particularly in areas where they have greater expertise and multiple parties are looking to develop a precinct (see Queensland example in LNG export discussion below).

Creating a supportive business and regulatory environment: Regulatory and tax settings that enable investment and innovation, including consistent standards, reporting requirements and regulatory certainty, are important to achieve the greatest benefits. These include policies that provide incentives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to global efforts to slow climate change.

Governments should avoid playing more commercial roles:

Funding capital costs: Private companies are far better placed than governments to assess the risks and rewards from capital-intensive investment. Exploiting these may require complex joint ventures (as in the development of Australia’s LNG export industry) and government may still need to play an important coordinating role, but commercial decisions that do not involve shared natural monopoly infrastructure are better left to the private sector.

Subsidies for clean energy exports: Production subsidies for particular technologies or products in other countries make it harder for Australia to compete. Subsidising the same technologies will exacerbate global supply constraints, driving up costs and skill shortages. Subsidies are also an expensive way to cut emissions, compared with emissions pricing, due to the fiscal costs and promotion of over-consumption by reducing prices. Projects should focus on sites with a sustainable comparative advantage rather than those that need government funding to compete.

Universities and VET providers need to partner on research and training

Education providers are often the “anchor institution” in innovation precincts and are an essential partner for clean energy precincts. Through industry placement programs, research partnerships and executive-level forums, education providers can enable technological advances and support the flow of talented researchers and students to commercial partners.

Strong relationships between precinct tenants and education providers can also help to develop courses and training that respond to industry needs. This is particularly critical given clean energy is already facing skills shortages.

Businesses should invest and collaborate to build competitive advantage

Businesses need to evaluate the commercial opportunities available to them and invest accordingly. Even under scenarios with substantial government support, the majority of capital investment for Australia to become a leader in clean energy exports is likely to come from the private sector.

Clean energy precincts adopt a "collaborate to compete" model, where participating businesses align their strategies and processes to achieve a competitive edge and seize new opportunities.

This year, Australia’s two biggest mining companies BHP and Rio Tinto announced a collaboration with steelmaker Bluescope Steel at Port Kembla to overcome the technical challenges of green steel production.

Reusing byproducts and using shared infrastructure can lower the cost base while reducing resource use through a more circular approach. In WA, the Kwinana energy hub hosts an estimated 178 exchanges of byproducts between 54 companies, with the initial tenant, BP, scoping opportunities to supply green hydrogen to other participants in the Kwinana industrial area.

Collaboration between businesses can raise concerns about anti-competitive behaviour. Two factors reduce this risk in industrial clean energy precincts: participants are generally pursuing complementary activities rather than being in direct competition; and where they supply competitive global markets for products such as green steel or ammonia, collaboration does not harm local consumers. This should be considered by the Federal Government’s competition review, which has been directed to provide advice on issues raised by the net-zero transformation.

Clean energy precincts: How to seize the green export opportunity

A framework to prioritise government support

Australian governments are increasingly recognising and supporting the potential of clean energy precincts, but there is no overarching framework to ensure support goes to the best projects in the best locations. Support from one level or department of government is often stymied by unnecessarily cumbersome planning processes imposed by another. We propose a simple framework to classify and prioritise how governments can support these developments.

Governments can enable, guide or invest in precinct development

There are several ways governments can support clean energy precincts:

- Policies that enable support broad economic activity and focus on fostering the conditions for the private sector to establish precincts;

- Measures can guide proponents to a specific technological or economic outcome but are not firm-specific; and

- Where governments invest, they become an active partner in development, channeling significant fiscal or administrative resources toward specific precincts.

Good policy processes such as transparent cost-benefit analysis are critical at all stages of the framework, but they become more important the more support a government provides. For example, where governments move beyond enabling to guiding precincts, some measures, such as infrastructure provision, can be expensive if the wrong technologies or locations are chosen. There is a higher risk for the public when governments invest in precincts, as the adverse consequences of supporting projects without a sustainable comparative advantage increase. We recommend governments avoid investing in projects without first conducting rigorous analysis informed by thorough community consultation.

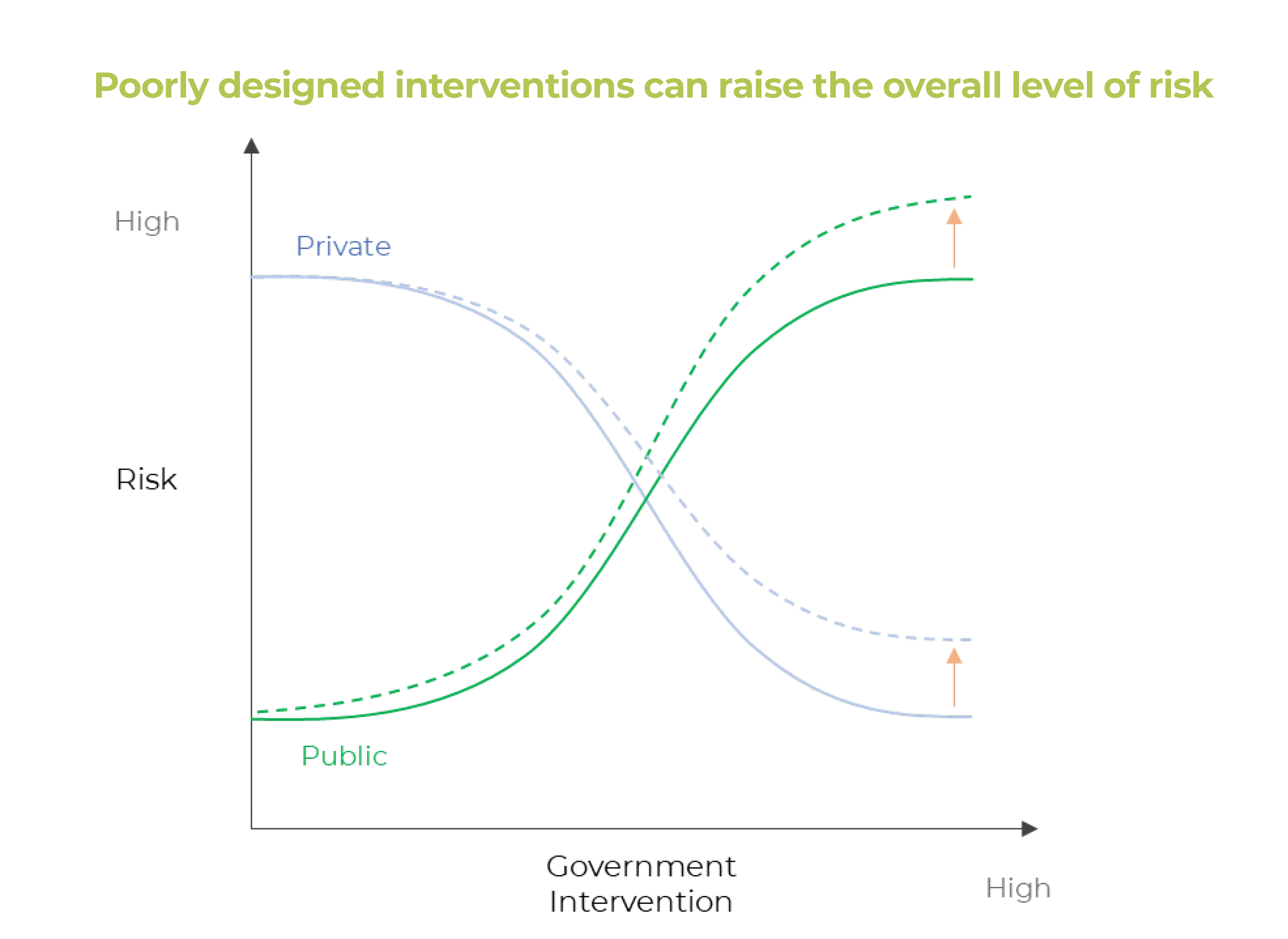

Government investment transfers risk, rather than removing it

Greater government support transfers project risk toward the public, as it must be financed by debt, taxes or reduced spending elsewhere. Sharing risk can help projects to proceed, but governments and the public also need to share in the benefits of successful projects, to offset the costs of inevitable failures. Attaching conditions to government funding, such as a requirement for profit-sharing, is one way government investment can lead to transformation, rather than just subsidies or handouts.

Targeted government investment is most likely to offer overall benefits when it supports new technologies, as benefits from research and innovation accrue beyond a single organisation. Targeted public support for research and development has the potential to better direct and “crowd in” private innovation. For hydrogen, for example, international experience indicates targeted support is necessary because of the substantial uncertainty facing individual firms, but that it is important to allow knowledge to flow across firms and for newcomers to benefit from publicly funded research.

There is also the potential for government action to raise the overall level of risk for all parties.

Poorly designed or implemented interventions that see resources allocated away from their most productive use can cause long-term harm for local economic development.

Large-scale financial support without rigorous selection criteria can encourage rent-seeking or lead firms to expect ongoing support. This increases exposure to sovereign risk if government policy changes.

Malaysia’s failed BioValley precinct demonstrates how poorly executed policy can waste significant resources. Government officials attempted to coordinate all aspects of this biotechnology precinct from the top-down, without a strong understanding of the technologies involved, the demand for end products, or the capacity of local labour markets to supply workers. Despite the government channeling funding into the project, private sector partners shunned the opportunity, and BioValley failed.

The shifting risk profile of different policy interventions means support from government needs to be highly targeted, situation-specific and informed by community engagement.

Governments should enable and guide precinct development

Before committing to large-scale investments, governments should focus on policies that enable and guide, which target fundamental barriers to precinct development. AGL’s experience with low-carbon industrial energy hubs underlines the importance of government support for education and training, enabling infrastructure, and simplified planning and permitting (Case study 5).

A lack of coordination and consistency between planning agencies and disjointed, overlapping interactions between different levels of government are well-known constraints for renewable energy projects, and have proven difficult to navigate for even the most sophisticated and well-resourced energy companies.

Similarly, regulations that have not kept pace with emerging technologies frustrate the ability of business to understand the commercial potential of sites. A lack of policy certainty has also undermined the confidence needed to assure international partners and spur investment in large-scale projects.

These are areas where government is well-placed to provide support and should be the first targets of action. As highlighted in Case study 4, financial backing counts for little when fundamental challenges of site permitting go unresolved. As responsibility for planning falls predominantly on initial precinct proponents, inflexible processes can delay project commencement and the realisation of broader economic benefits.

Consistent with the Productivity Commission’s findings for major projects, there is a need for reforms to improve strategic decision-making to consider cumulative impacts, reduce regulatory overlap and duplication, and improve timeframes and coordination.

For large-scale developments, a single point of contact or lead agency can better coordinate and facilitate approvals. We recommend that governments across different levels and departments cooperate to update and simplify planning for clean energy precincts, while maintaining environmental and community protection.

Governments should also play a key role in coordinating and leading community engagement. Quality consultation can help leverage local networks, understand infrastructure adequacy and assess planning-system constraints. This can help policymakers identify where further interventions can make the largest impact at least cost. Genuine engagement will help foster a shared sense of ownership among local communities that supports enduring social licence.

Government investment requires deeper analysis

Where substantial government investment in precincts is considered, strong due diligence must be conducted to assess long-term commercial prospects. While the scope of this analysis will vary with the action being considered, it may include:

- Cost benefit analysis;

- Growth and market share estimates for precinct outputs;

- Comprehensive analysis of comparative advantage;

- Understanding the precinct’s role in value chains;

- Analysis of the global competitive landscape; and

- Understanding governance capabilities.

For example, governments may choose to enable and guide a private sector-led clean energy precinct that seeks to export green ammonia, leaving commercial aspects around long-term competitiveness to project proponents. But where governments go further and choose to co-invest, there is a need to analyse independently future demand for ammonia and the potential for the precinct to have a sustainable comparative advantage in global markets.

Rationalising the large number of funding programs for clean energy precincts would make detailed analysis more feasible while reducing complexity and allowing competing projects to be directly compared. This has been the approach taken to ensure the best projects are funded under the $2 billion Hydrogen Headstart program. The growing number of investment decisions taken by the Federal Government must be backed by sound and consistent analysis. Existing bodies such as the Net Zero Economy Agency (and proposed Authority) or Australian Renewable Energy Agency could be tasked with undertaking and publishing independent analysis of potential payoffs. Structured information sharing will be important to ensure consistency and help rank projects if the analysis is not undertaken by a single body.

Evaluation is important to monitor progress

The long lead time for precinct maturity means policy evaluation and community feedback loops are essential. Evolving technologies, the agility of planning processes to respond to changing land-use requirements and shifting demand in global markets can all change the nature or extent of policy support required. Accepting that not all projects will succeed means that support must be periodically recalibrated; the failure of governments to stop supporting unsuccessful technologies, projects or firms has undermined industry policy in the past.

A strong coordinating body within the precinct can play a valuable role in bringing stakeholders together to identify emerging challenges and opportunities, and communicating these effectively to policymakers. Evaluation of financial support that is targeted at specific sectors or technologies is particularly important given limited and mixed evidence of the effectiveness of such policies internationally, and the potential for digital technologies to make evaluation easier.

Conclusion

Clean energy precincts present significant opportunities for Australia to capture emerging green export markets. Knowledge spillovers, economies of scale through shared infrastructure, and circular practices such as reusing byproducts can help Australian industrial regions seize these opportunities.

Governments, industry and education institutions are already starting to embrace precincts. Yet at the same time, complex, fragmented and in some cases outdated planning and permitting processes are delaying progress without necessarily delivering better environmental or community outcomes.

Governments should start to enable these projects through community consultation and removing barriers to precinct development. High quality consultation gives communities, including First Nations groups, the tools and opportunities to participate in and shape the growth of precincts.

All levels of government need to cooperate to update and simplify planning for clean energy precincts, while maintaining environmental and community protection. A key step to guide new precincts is the creation of single points of contact or lead agencies for permitting.

Governments are already making substantial investments. They must be accompanied by deeper, unbiased analysis to ensure public funds go to precincts with the greatest sustainable comparative advantage.

Developments should be underscored by a clearly articulated purpose that is understood and embraced by all tenants, with measurable objectives to allow evaluation and updating of priorities. A coordinating body is needed to support the evolving goals of the precinct, promote the development of internal and external networks and connect stakeholders to commercial or research partners.

With collaboration and coordinated action, Australia can embrace clean energy precincts and seize the green export opportunity.