PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

Australia enjoyed an enviable record of strong and sustained economic growth over nearly 30 years, coming to an abrupt end with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

The pandemic brought widespread disruption and upended the lives of many, and saw economic growth plummet in its early stages.

But the latest data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey surprisingly shows Australian households felt more financially secure at the time.

Downloadable resources

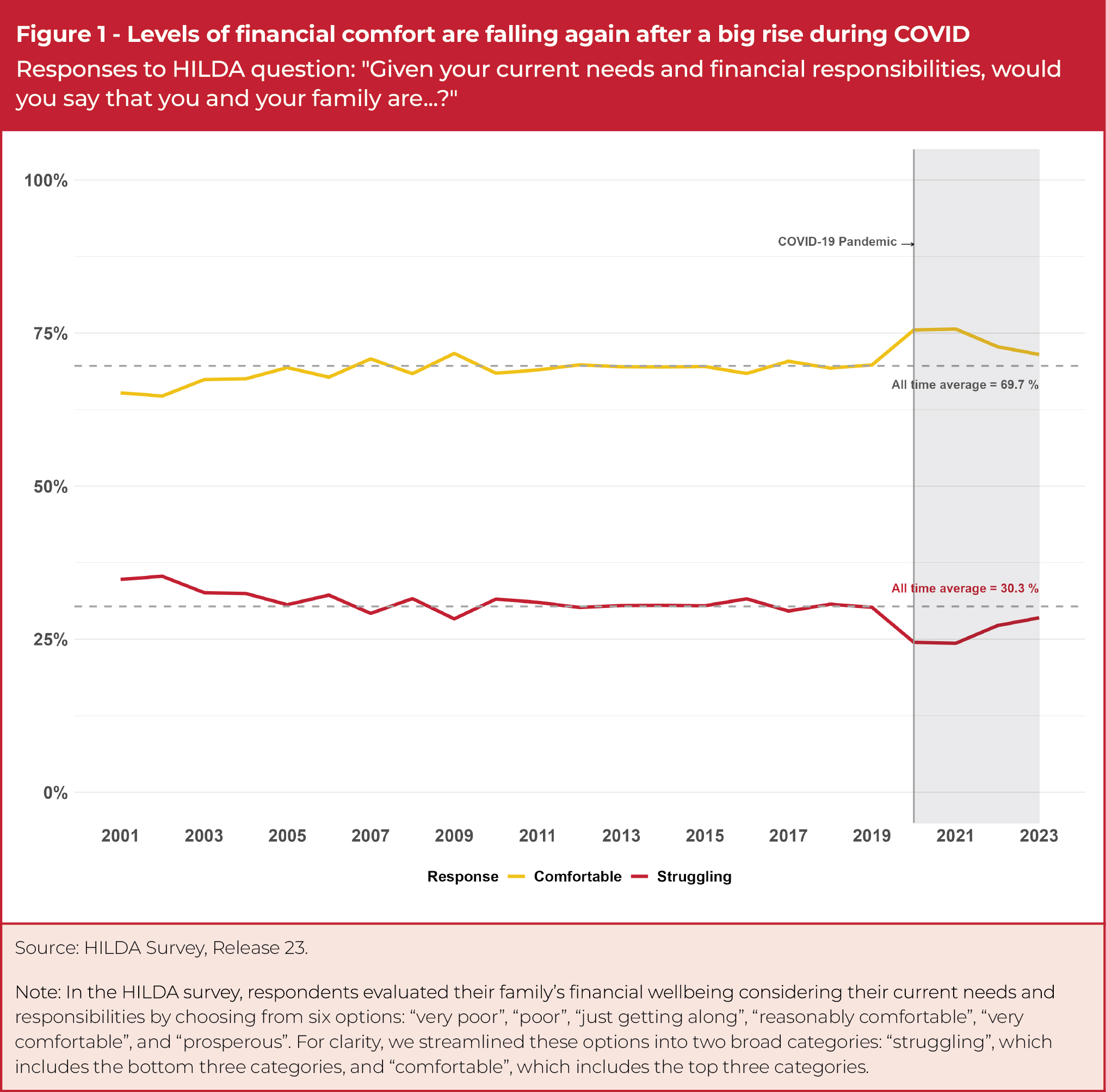

April 2025 Financial Wellbeing Data insight (PDF 2653KB)The HILDA questionnaire asks households to assess their financial wellbeing by selecting one of six descriptors ranging from “prosperous” to “very poor” based on their current needs and obligations.

We grouped these responses into two broader categories: “comfortable” and “struggling”.

Australians’ financial wellbeing had been relatively steady until the onset of the pandemic. In 2021, however, the proportion of people feeling financially comfortable spiked, peaking at 75.7 per cent, an increase of 5.9 percentage points since 2019 (Figure 1).

This counterintuitive trend shows headline figures about the economy don't always match the individual experience of financial security.

The HILDA survey doesn’t ask people what influenced their level of financial comfort. Many potential factors could therefore explain the boost in financial wellbeing during the pandemic.

Notably, the household savings ratio surged to 23.9 per cent in June 2020, which was more than four times its level in the same month in 2019. This dramatic increase was driven largely by a sharp drop in household spending levels around that time, particularly on transport and dining out. The household savings ratio remained above the pre-pandemic average until September 2022.

In 2021, another measure of financial security, the ANZ Financial Wellbeing Indicator, found saving and spending behaviours were the largest behavioural drivers of financial wellbeing.

This suggests that, coupled with the increase in government support payments, the rise in the household savings ratio and the drop in household spending helped drive some of the improved pandemic-era financial wellbeing identified in our analysis.

Importantly, however, ANZ also identifies socio-economic characteristics such as health, employment and home-ownership status as playing a key role in financial wellbeing.

The role of housing

The HILDA data shows financial wellbeing started to decline in 2022. This occurred as rising costs of living strained household budgets due to high inflation from 2022 to 2023.

In 2023, nearly one in three Australians reported difficulty meeting their current needs and financial obligations. Nevertheless, while financial wellbeing was declining from its pandemic-era bump, it was still above the pre-pandemic average, with 71.5 per cent of Australians reporting they felt financially comfortable that year. If this trend is sustained, it may indicate a perception of rising living standards.

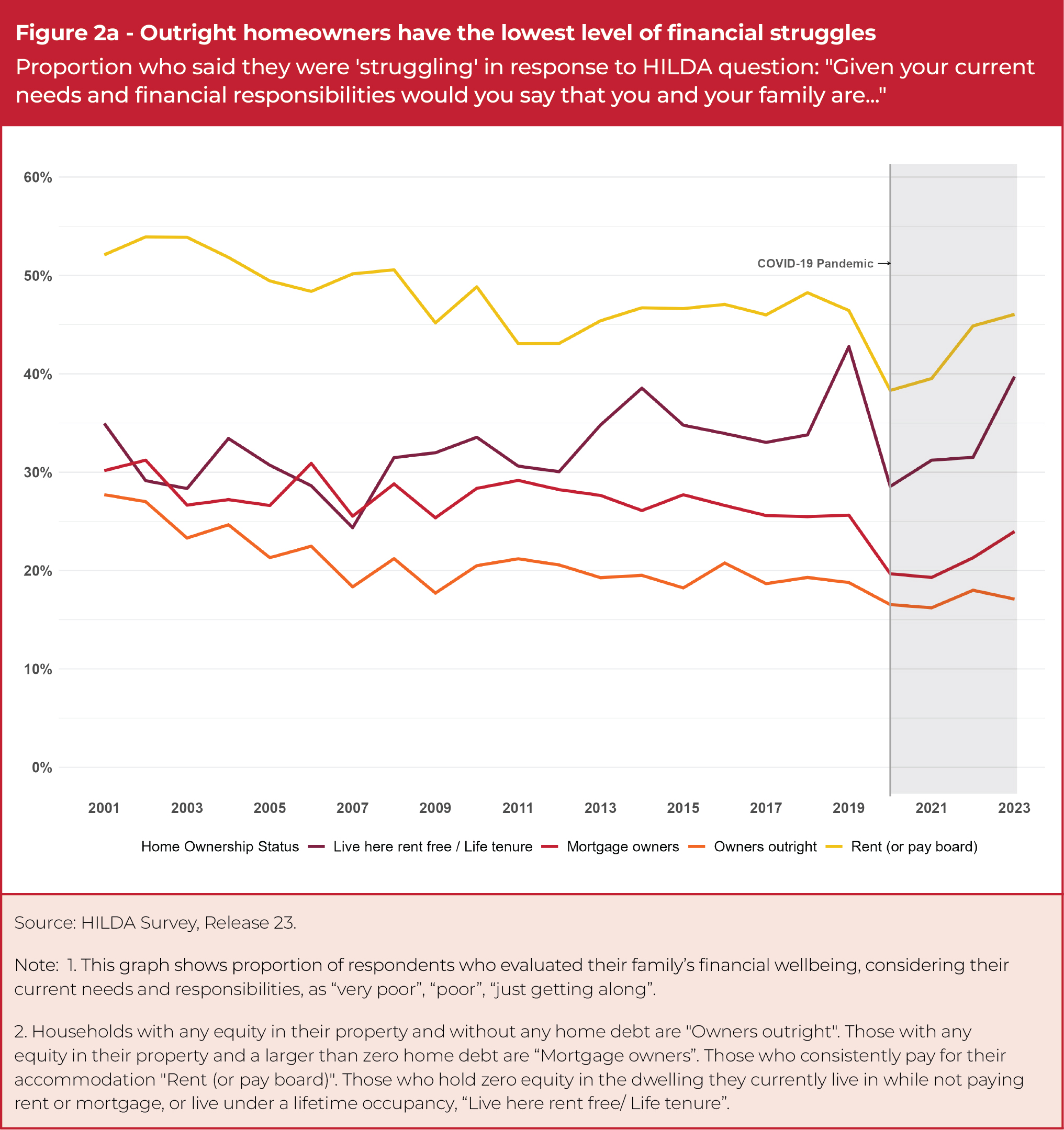

Closer analysis of the HILDA data, however, shows some households are faring better than others. Notably, people who owned their homes outright had the highest levels of financial wellbeing in our analysis (Figure 2a).

ANZ’s Financial Wellbeing Indicator shows those who own their home outright have higher average financial wellbeing (78 out of 100) than those with a mortgage (66 out of 100) and those who rent (49 out of 100).

It also points out that “a key driver of the impact of life stage was the affordability of repayments – whether someone was finding it easy or difficult to pay their mortgage or rent”.

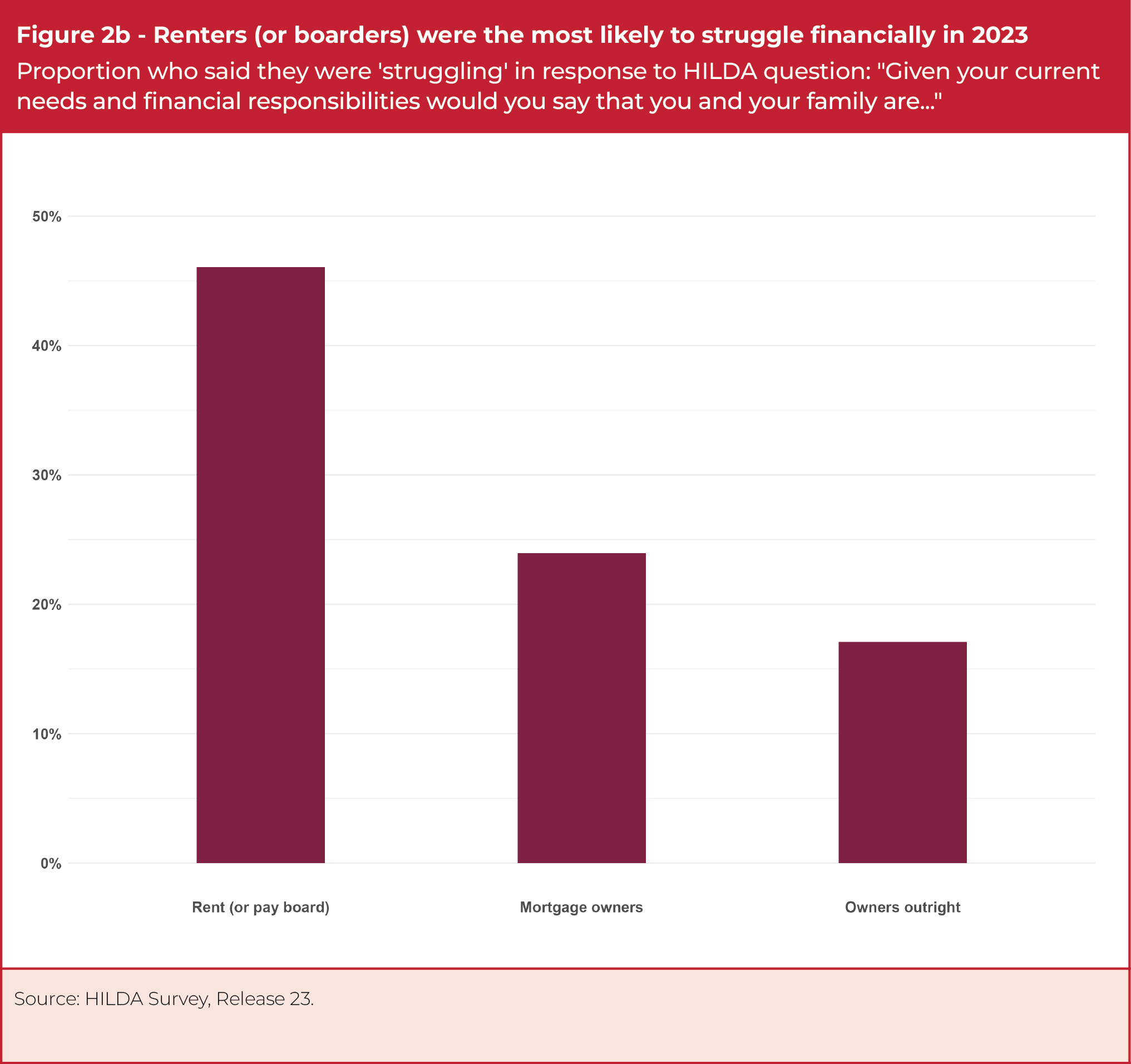

Our analysis shows approximately 46 per cent of renters reported financial struggles in 2023, nearly triple the rate of outright homeowners at around 17 per cent (Figure 2b).

This striking disparity reflects the pressure on renters’ household budgets from skyrocketing rental prices (Figure 3) and housing prices relative to household disposable income.

Renters were faced with both a higher cost of living and the increased difficulty of transitioning to homeownership due to declining housing affordability.

Meanwhile, despite facing rising interest rates that pushed up mortgage repayments, just under one-in-four mortgage holders reported financial difficulties, suggesting the wealth-building aspect of property ownership has potentially provided some buffer against perceptions of economic hardship (Figure 2b).

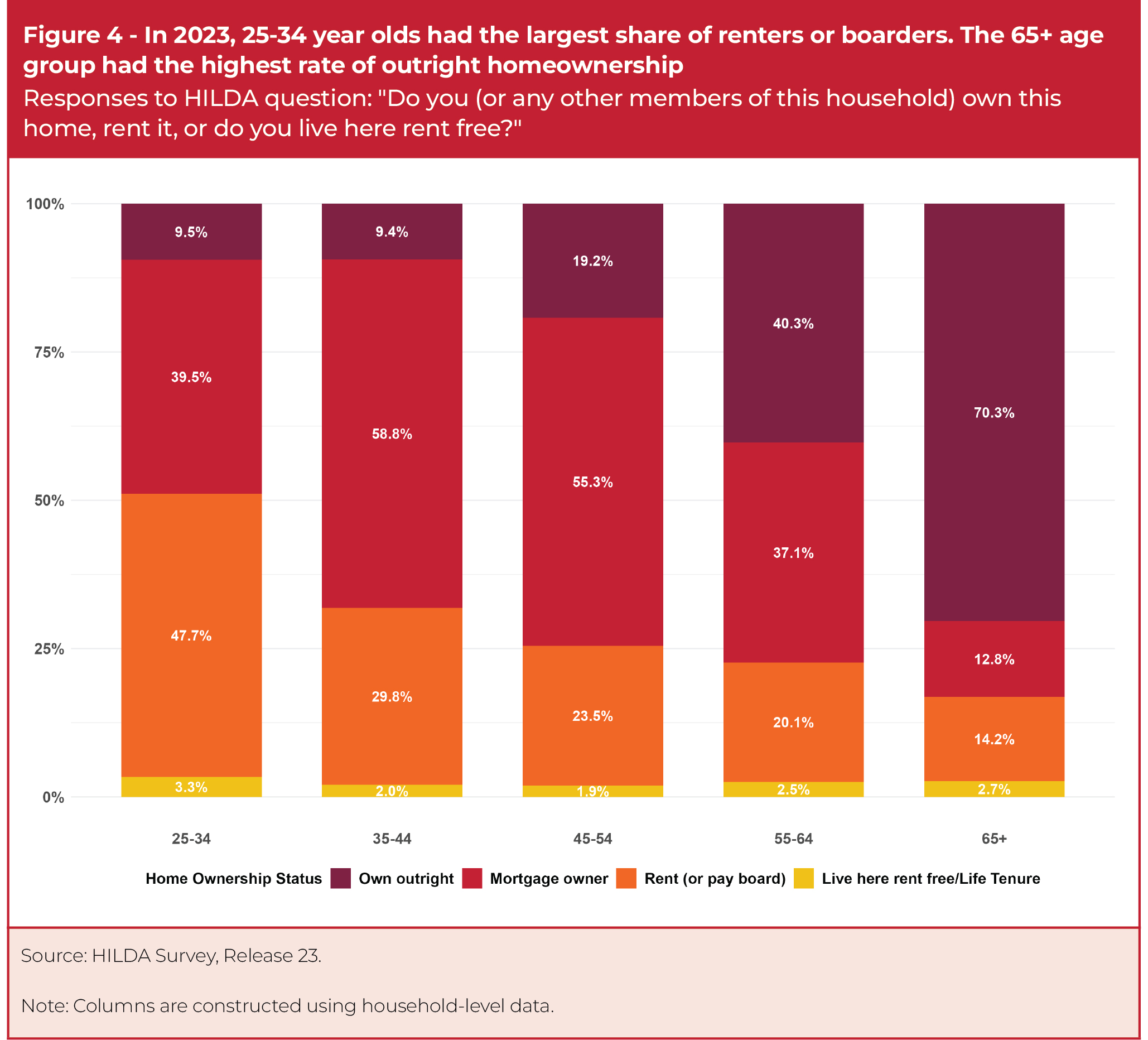

The impact of these housing and rental market pressures is particularly acute for younger Australians, who face the same cost burdens as older cohorts but possess significantly fewer financial resources to manage these expenses.

This financial vulnerability is reflected in housing tenure patterns across age groups. Australians aged 25-34 are the most likely of any age group over 25 to be renting, with approximately 48 per cent in such an arrangement (Figure 4).

Meanwhile, 70 per cent of those aged 65 and above own their homes outright. Importantly, both non-pensioners and age pensioners share that same high level of outright home ownership.

This disparity highlights an intergenerational gap in housing accessibility. It suggests the weaker financial wellbeing of renters, who are predominantly younger Australians, is in part due to the cumulative impact of rising rents and escalating living costs, with limited opportunities for wealth accumulation through home ownership.

While the pandemic unexpectedly boosted many households' financial comfort through increased savings and government support, the post-pandemic recovery has highlighted deep divisions in our society.

Younger Australians have been hit particularly hard, with multiple sources of financial difficulty.

Without targeted policy intervention, we risk entrenching a system where financial security becomes increasingly dependent on home ownership status and inherited generational wealth.

Do we really want to create a future in which today’s young Australians may never be able to achieve the same financial wellbeing in their old age as their grandparents enjoy today?

Wenting Hu was an intern economist at CEDA.

This paper uses unit record data from Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey [HILDA] conducted by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author[s] and should not be attributed to the Australian Government, DSS, or any of DSS’ contractors or partners. DOI: 10.26193/NBTNMV