Make a tax-deductible donation to support CEDA's agenda and help accelerate change

30/10/2023

Australia has a diverse population with a rich history of migration. Over the years, people from all corners of the globe have made their home in this vast and varied continent, bringing with them their skills and experience.

While much consideration is given to ensuring that recent immigrants, particularly those on skilled visas, have the right skills and qualifications, there has been much less policy focus on ensuring that immigrants have the right work environment to contribute to the full extent of their capabilities.

With Australia currently facing record-low unemployment and persistent skills shortages, every lever needs to be pulled to address the increasing gap between supply and demand for skilled workers. Prejudice is one such barrier that needs to be addressed to unlock Australia’s workforce potential.

Prejudicial attitudes based on factors such as ethnic and racial backgrounds, gender, sexuality, religion, family roles, and age, among many others, remain persistent challenges within the workplace.

For immigrants, prejudice in a workplace setting can manifest as barriers like name discrimination; hiring biases; and skills mismatch, where immigrants find themselves in lower-paying positions despite coming from professional backgrounds and being overqualified for their roles.

How to reduce prejudice

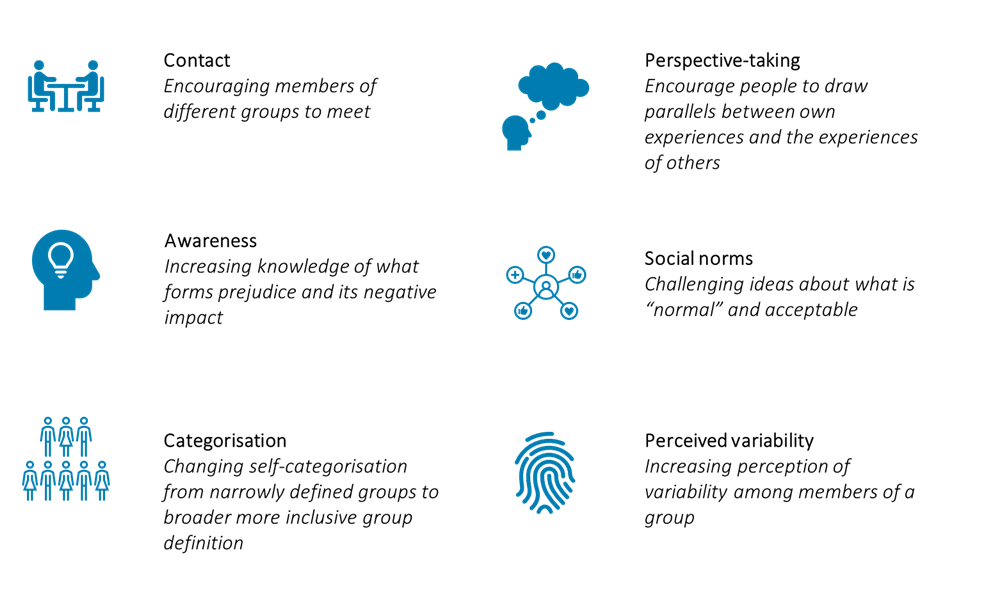

The good news is that a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of prejudice reduction interventions that have been tested in real-world environments found a number of proven ways to reduce prejudice. These strategies include contact, awareness, categorisation, perspective-taking, social norms and perceived variability (see graphic below).

The most common approach is contact (used in 49 per cent of interventions). These approaches work by encouraging people from different groups to meet. An example of this type of intervention is students from a Christian school working together with students from a Muslim school on a climate-change project.

The next most common approach is awareness. These interventions reduce prejudice through educating participants about what constitutes prejudice and discrimination, and the negative impacts of prejudice. An example is asking questions relating to common misconceptions about different groups and then providing correct information afterwards – in other words providing “myth-busting” information.

However, these commonly used approaches are not necessarily the most effective. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that a lesser-used approach of perceived variability has a greater average effect on reducing prejudice. Perceived variability works by increasing perception of variability among members of a particular group. In doing so, it becomes harder to draw negative stereotypes and form prejudice against members of that group.

The suitability of each of these strategies for a specific workplace or setting will depend on: the context and drivers of prejudice that may be specific to the workplace or industry and the availability of resources; any challenges associated with implementing the strategy; and of course, the design of the intervention, including adaptations for the specific setting. Considering these factors at the outset will help to ensure the most effective approach is taken to creating an inclusive environment where everyone is able to contribute to the best of their capabilities.

Figure: Prejudice reduction interventions tested in real-world settings

Source: Hsieh et al (2021), and see also ABC radio report

While tackling prejudice and discrimination is not traditionally thought of as labour-market policy, it is critical now, more than ever before, to ensure that everyone has an inclusive work environment, to unlock the full potential of Australia’s labour market.

Tariq, M. and J. Syed, Intersectionality at Work: South Asian Muslim Women's Experiences of Employment and Leadership in the United Kingdom. Sex Roles, 2017. 77(7): p. 510-522.

Masser, B., K. Grass, and M. Nesic, 'We like you, but we don't want you'-The impact of pregnancy in the workplace. Sex roles, 2007. 57(9-10): p. 703-712.

Corpuz, E., C. Due, and M. Augoustinos, Caught in two worlds: A critical review of culture and gender in the leadership literature. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2020.

Nelms Smarr, K., R. Disbennett-Lee, and A. Cooper Hakim, Gender and Race in Ministry Leadership: Experiences of Black Clergywomen. Religions, 2018. 9(12): p. 377.

Holder, A.M.B., M.A. Jackson, and J.G. Ponterotto, Racial Microaggression Experiences and Coping Strategies of Black Women in Corporate Leadership. Qualitative Psychology, 2015. 2(2): p. 164-180.

https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjso.12509

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022103112000108

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10508619.2018.1431759

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.003

Hsieh, W., Wickes, R. & Faulkner, N. What matters for the scalability of prejudice reduction programs and interventions? A Delphi study. BMC Psychol 10, 107 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00814-8

https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjso.12509 and see also https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/lifematters/the-best-ways-to-tackle-prejudice/102357052