Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

10/03/2015

One of the key observations of the 2015 Intergenerational Report is a projected increase in the dependency rate driven primarily by the combination of an ageing demographic and longer life expectancy.

The number of people of working age relative to the number of people aged 65 and over is projected to halve from current levels by 2054-55.

Attitudes of individuals and employers, along with a number of government policies, will be important drivers of retirement decisions of mature age Australians over the next decade.

Extending the average age of retirement by a couple years would largely offset the challenge of an increasing structural government budget deficit as highlighted in the Intergenerational Report.

Additional private income from the extra wages and superannuation would also better meet the established high spending desires of the baby boom generation which are well above the Age Pension payment. For many mature aged, extra years of work, especially with flexible hours, will add to life esteem over and above the dollars.

The statistics: mature aged workforce

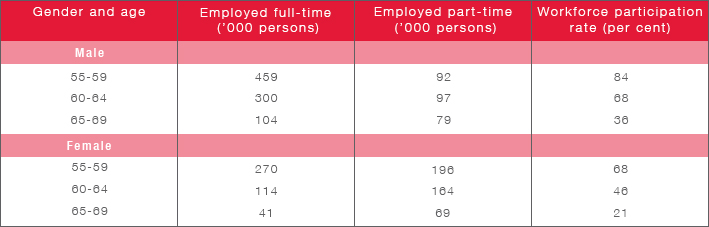

By way of background, Table 1 shows Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, Catalogue 6238.0, Table 1) data for employment of males and females aged 55 and over.

For males the workforce participation rate falls from 84 per cent for those aged 55-59, and most with full-time jobs, to 68 per cent for those aged 60-64, and down to 36 per cent for the 65-69 age bracket with most of the fall in full-time jobs.

Female workforce participation rates are lower for each age category, and for those employed they make up a much higher share of part-time jobs.

Table 1: Labour Force Participation of Mature Age Australians, 2012-13

Clearly, there is a large potential to increase the participation rate for males age 60 and above, and more so for females age 55 and above.

Employment supply and demand

Employment of the mature aged, as is the case for general employment, depends on the interaction between employee willingness and desire for employment, labour supply, and employer demand for labour inputs to produce valued goods and services.

Mature age labour supply depends on the income options during retirement including accumulated superannuation and other private savings, and eligibility for government payments.

In particular access to the Age Pension and the disability support pension impact retirement decisions. These payments are relative to the after-tax returns from wage and salary income associated with further employment.

Employee health, circumstances of other family members, and preferences for work versus retirement are also important labour supply factors.

Employer demand for mature age employees depends on the productivity and labour costs of the mature age relative to younger employees, the general state of the economy, and social attitudes.

This labour demand and supply picture can be disaggregated into full-time and part-time employment. Outward shifts in either the supply of, or the demand for, mature age labour will result in a higher participation rate and employment.

Government policy, the economy and workforce participation

A number of on-going structural changes in the economy are projected to encourage higher rates of labour force participation of the mature age.

Further increases in health, together with higher education and a decrease in the share of physically demanding jobs, will extend preferred retirement ages.

Already younger cohorts of females have higher participation rates than their mothers.

Through additional years of employment a larger share of people are likely to acquire larger private savings, including superannuation.

A combination of longer and healthier life expectancy; increases in desired incomes during retirement; and greater financial numeracy are likely to require people to amass such savings.

Several arms of government policy also directly affect decisions of when to retire including changes to the Age Pension and access to superannuation.

Factors contributing to retirement decisions include the legislation in place which extends the eligible age to 67 by 2023, and proposals to further extend to age 70 by 2035, tighter restrictions on access to the Age Pension, including eligible age and income and asset tests, and less generous payments.

An increase of the current age 60 for tax free access to superannuation would increase mature age labour supply.

Means testing of the Age Pension, and associated allowances, in combination with income taxation create very high effective tax rates, especially for part-time mature age workers, which reduces the incentive and reward for continued employment.

Effective macroeconomic policyto ensure full employment, such as fiscal balance over the business cycle and counter-cyclical monetary policy, would reduce the large numbers of mature age employees who retire early because of retrenchment and the lack of new job opportunities.

Indirectly, excellent education and health policies which increase human capital support later retirement decisions.

The role of business and community organisations

Attitudes of both employers and employees, and social norms, can play positive roles in supporting later retirement ages.

In the workplace, these include flexibility of employment and work packages, and a willingness to acquire and develop new skills.

Generally, the facts of a longer and healthier life, together with recognition that society can consume no more than what it produces, should shift social and political expectations towards productive employment for longer periods.

Business and community organisations can, and should, assist in promoting these changes.