Make a tax-deductible donation to support CEDA's agenda and help accelerate change

16/07/2024

Productivity growth has driven prosperity in developed and emerging economies since the Industrial Revolution. But it has now stalled in many of these economies, unfortunately nowhere more so than in Australia. Over the last decade, we have experienced the lowest productivity growth in 60 years at 1.2 per cent a year, with Australia dropping to 16th in the OECD productivity rankings from sixth in 1970.

Why is this happening, and what can we do about it? Do Australians need to work harder, or smarter? How important is investment in digital and renewable energy technologies? Should we pay more attention to our research and skills infrastructure, or to management quality and enterprise ‘absorptive capacity’? These questions are critical not just to abstract economic debate but also to future living standards in an increasingly knowledge-driven, decarbonising world.

While real incomes in Australia were cushioned by our recent commodity boom thanks to the accompanying boost to the terms of trade, this provided a merely temporary ‘sugar hit’ that was superseded by current ongoing wage stagnation. The impact on the Australian workforce has been compounded by a lower share of the more limited productivity gains as companies seek to maximise profitability through price inflation.

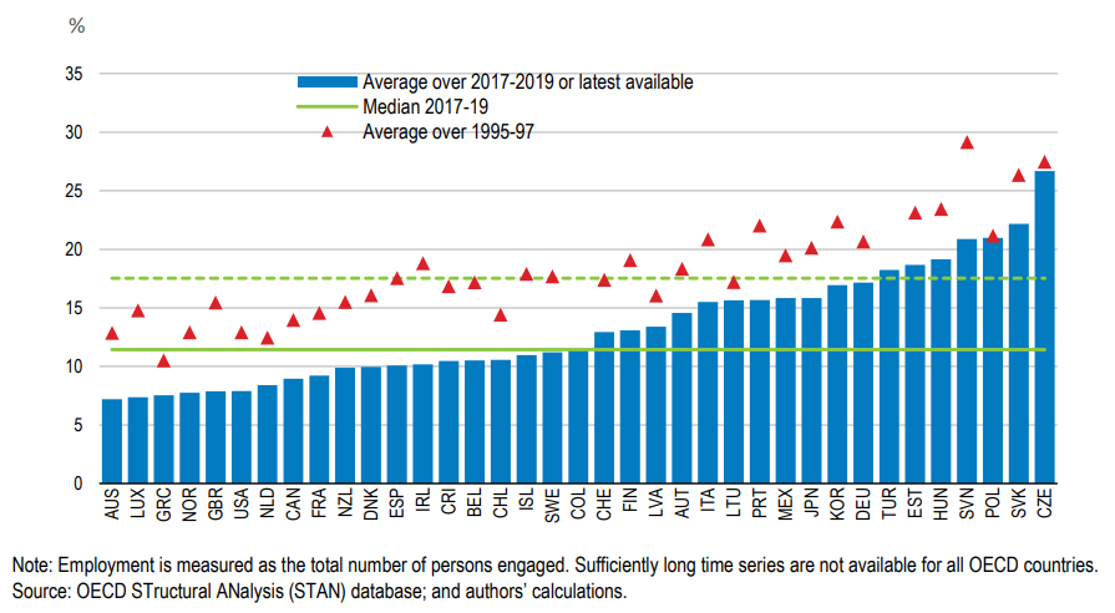

The commodity boom also rendered our trade-exposed industries less competitive – or in some cases uncompetitive – in global markets through appreciation of the dollar. This was the ‘resources curse’ in action, which along with tariff reductions in the 1980s and ’90s reduced manufacturing to six per cent of GDP, compared with around 30 per cent in the 1960s and ’70s. As a result, Australia is now the least self-sufficient economy in the developed world.

Australia has the lowest share of manufacturing of any OECD country

While the Norwegians imposed a 76 per cent resource rent tax on their North Sea oil and gas assets, which enabled them to invest in a more resilient, diversified future through the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, we followed the UK’s dismal market-driven North Sea experience by squandering our windfall gains on a short-lived consumption boom. This had the further effect of reinforcing our narrow trade and industrial structure.

The latest Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity, which measures the diversity and knowledge intensity of a country’s export mix, relegates Australia to 93rd of 133 nations, just behind Uganda. Neoclassical economists accept that this simply reflects our supposed comparative advantage in unprocessed raw materials such as iron ore and coal. The problem is that we then become increasingly vulnerable to external shocks such as commodity price volatility and supply chain disruptions.

Moreover, the traditional market model of comparative advantage denies Australia the more promising strategic opportunity to identify and capitalise on areas of potential competitive advantage in the high productivity, high-skill jobs and industries of the future, including advanced manufacturing. Instead, with this model we will be locked into low-productivity, low-wage industries, with limited scope for uplift through technological change and innovation.

In this context, Australia’s desultory 1.68 per cent share of R&D spending in GDP continues to slide, while the average of OECD countries climbs to around three per cent, with some like Korea, Israel and Switzerland investing four to five per cent. What do they know that we don’t? They know that future living standards depend on productivity growth, that productivity growth depends on investment in research, innovation and skills, and that these all contribute to a high-value adding net-zero industrial structure.

Australia has the lowest share of R&D of any OECD country

Another way of looking at Australia’s long-term performance is with the location quotient (LQ) index devised by the Washington-based Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF). This index identifies the share of advanced industries in the economy compared with its share of the global economy. If Australia had the same share of advanced industry output as the global economy, its LQ would be 1.00.

In 1995, Australia’s advanced industries’ LQ was 0.56, meaning it had 44 per cent less advanced industry production as a share of its economy than the world. But by 2018, its LQ had fallen to 0.41, ranking 51 of 74 nations, just ahead of Costa Rica and behind Iceland. To compare, America’s LQ is 0.94, China’s 1.34 and Germany’s 1.74.

Even the UK and Canada, whose manufacturing sectors have likewise been hollowed out by relentless deindustrialisation, lead Australia with 0.80 and 0.60 scores. For Australia’s advanced industry output to be the same share of its economy as the global average, output would have to increase by almost 1.5 times or $105 billion.

The Future Made in Australia initiative is an opportunity to diversify and transform our industrial structure in the context of the global energy transition and the desire for sovereign capability in areas of current and future competitive advantage, as well as possible geopolitical risk. The scale of the opportunity is huge, with the market for clean energy industries alone estimated to be worth $15 trillion by 2050.

For a mission-led industrial strategy to provide the boost to productivity that Australia needs, it will require a coordinating institutional focus in government and close collaboration, including co-investment, between industry and research and education institutions. This means not just addressing ‘market failure’ but shaping markets to build innovation and enterprise capability in global value chains.

There is now broad recognition around the world that government must play an active role in creating a more inclusive and dynamic knowledge-driven economy, particularly to address the increasingly interconnected challenges of productivity and climate change. Key to addressing these challenges in Australia is the need to transform our outdated industrial structure and revive and reinvent our manufacturing capability.