Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

18/04/2024

Every great innovation starts with a market vision. Without it, even the most brilliant invention won’t become innovation.

Market vision is about seeing the world differently, so you can take advantage of a market shift before it happens.

The transition to net-zero emissions by 2050 is the biggest market shift of our lives. Exactly where we play in that massive shift is the hard part.

Australia is a leader in invention, our science is in the global top 10, but we lag in innovation (72nd globally).

When I became chief executive of CSIRO in 2015, we started working on a plan to get Australia to net zero. The realisation of just what an impossible challenge it was made it our market vision and drove most of our changes for the next eight years.

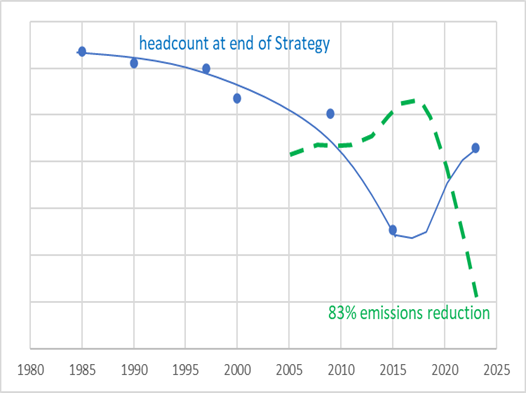

With one of the largest rural footprints in government, CSIRO’s emissions are, perhaps surprisingly, like those of a mining company. And despite CSIRO shrinking for the prior 30 years, its emissions stubbornly kept going up.

Given we wanted to reverse the decline, we also had to solve emissions. So the seemingly impossible challenge back in 2015 was: “Can we lower emissions while growing profitability?” This is the same question currently being asked in boardrooms across Australia.

In 2016, we started simple with energy efficiency. This gave us about 15 per cent reduction. Later, we analysed residential Australia and found up to 50 per cent reduction would be possible. The key was surrendering some level of control of our systems to intelligent agents (like AI) that minimise energy. This was Abe’s vision of society 5.0.

It got harder after that; we built one of Australia’s first large-scale off-grid solar storage systems to power a remote site. We invented FutureFeed to attack 15 per cent of Australia’s emissions in agriculture. We attacked another 30 per cent of Australia’s emissions in transport through hydrogen and ammonia fuels – and we turned a 30-year decline into growth.

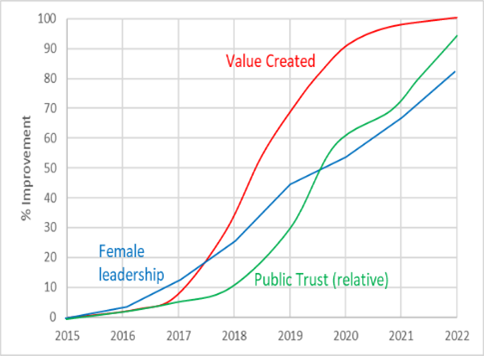

CSIRO’s Innovation catalyst strategy delivered some big wins. We doubled CSIRO’s value & delivered $400 million more revenue than any prior strategy, and $10 billion more value cumulatively. This drove the largest investment into science in CSIRO’s history and the creation of National Missions to solve Australia’s challenges, all targeted by our market vision.

Diversity of thinking created our market vision, which turned our invention to innovation. CSIRO became the first Australian enterprise to break into the Thompson Reuters-rated Global top 20 Innovators, but others must follow for Australia to deliver on net zero.

By the end of 2019 we delivered 83 per cent emissions reduction, turning 30 years of talking about climate change into real action, and making CSIRO a leading enterprise in net zero globally.

That last 20 per cent of emissions reduction is a truly wicked challenge. It needs ships, trains and planes to run on ammonia and hydrogen. But this is where Fortescue, where I am now a non-executive director, comes in.

Fortescue has a profound market vision for energy. It has set its sights on eliminating its own emissions within this decade. Fortescue too started with energy efficiency, which has made it the lowest cost iron ore producer. This is good for business and the planet.

In precision mining, the ore is imaged and precisely targeted to minimise energy use and environmental disruption. Extracting the ore needs massive diesel-powered diggers and trucks, but Fortescue already operates autonomous mining vehicles of its own design and developed fully battery-powered trucks.

To move the ore to market, we developed the Infinity Train, which unites the power of gravity, regenerative braking and lithium batteries taking lessons from Formula E race cars. We produce hydrogen as a byproduct of some of our mining processes, and this rides with the train as a power boost when needed, using its unique fuel characteristics, which batteries lack.

Batteries are great at storing energy, but chemical fuels have a unique ability to safely transport and release massive amounts of energy quickly. This is why hydrogen is so important.

Once delivered to Port Hedland, the autonomous train unloads and ore is loaded on our ships, robotically, again minimising energy waste. Hydrogen really comes into its own here for heavy transport. Because of its ability to rapidly store and release energy, it can power the ship, but it’s likely to be in the form of ammonia liquid fuel that fits within the existing global fuel paradigm.

Finally, coal is very hard to replace in steelmaking, but here too we believe hydrogen holds a key. The world needs hydrogen to work, and Australia needs hydrogen to fill the gap left when coal and LNG disappear.

All of this happened because the right market vision focused great Australian science on solving the most important problems. It must happen again and again until we all reach net zero together.

Hear from Dr Larry Marshall at the CEDA Climate and Energy Forum on 8 May in Brisbane. Join the conversation and register today.