PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

25/03/2025

The Albanese Government’s fourth Budget contains many of the hallmarks of a pre-election budget and as a result, it fails to address the long-term challenges facing the nation.

As expected, measures to address cost-of-living feature prominently.

While reducing financial stress on households is welcome, these measures do not grow capacity in the economy and could be better targeted.

Reducing student debt will forego $16 billion owed to the Australian Government. Increasing GP bulk-billing rates and disaster-relief payments are estimated to cost a combined $9.7 billion in new spending over the forward estimates.

These should only have a small impact on inflationary pressures. As should the additional $5 billion for higher wages and improving access in the childcare sector.

The inflationary impact of all spending decisions must remain front of mind for governments, particularly given the current global economic uncertainty. Keeping inflation under control remains the best avenue to address household cost-of-living concerns over the longer term.

Unfortunately, there is not enough restraint in this Budget. Cost-of-living relief remains poorly targeted, in particular the $1.8 billion extension to energy rebates, which continue to go to all households.

More concerning is the $17 billion in tax cuts over the forward estimates, which coupled with the broad-based energy rebate, risks stoking inflation.

The impacts of Cyclone Alfred could also push up inflation in the short-term in some sectors such as agriculture, as supply chains are hampered.

A combination of sluggish growth and increased spending is forecast to see a deficit in 2024-25 of $27.6 billion, bigger than forecast in December, growing to $42.1 billion in 2025-26.

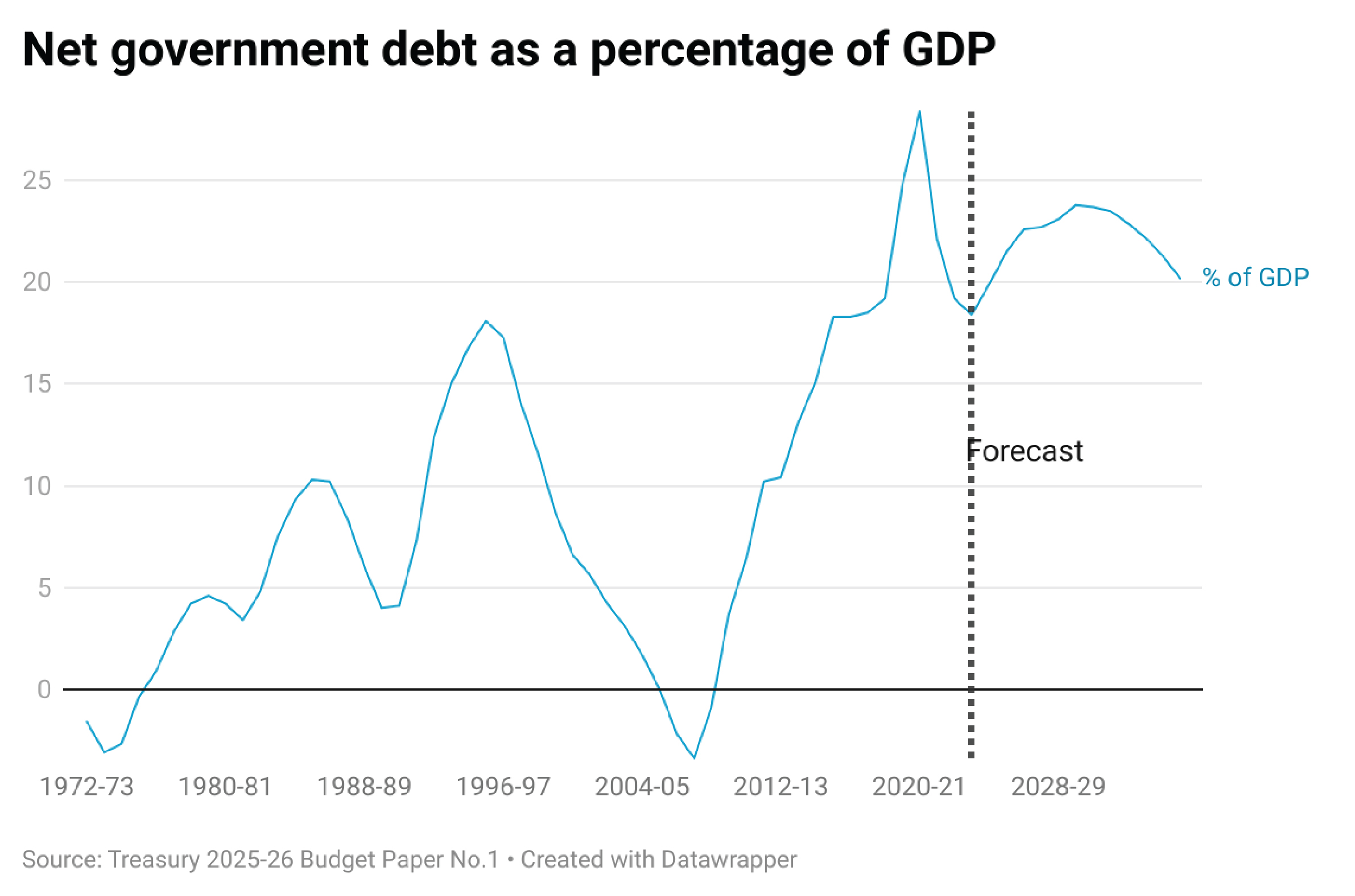

Disappointingly, this Budget does little to address the medium-term structural deficit, which is expected to total $179.5 billion over the forward estimates, with government debt to peak at 37 per cent of GDP in 2029-30.

Long-term budget sustainability is critical to ensure that Australia is resilient to future shocks in the global economy. The current economic uncertainty and geopolitical instability heighten the risk of these shocks.

CEDA continues to advocate for better evaluation of government spending. The Government should start a systematic review of program evaluations for better accountability and transparency through the Australian Centre for Evaluation. Given the budget position, it is critical this begins earlier rather than later.

Projected tax revenue is $6.6 billion lower than the 2024-25 mid-year update, due to the announced tax cuts, despite upward revisions due to a strong labour market and high commodity prices.

Tax reform remains the elephant in the room for this Budget. It contains some minor cuts to taxes, reducing the current 16 per cent tax bracket to 15 per cent from 2026-27 and a further cut to 14 per cent in 2027-28. This does not address ongoing concerns around bracket creep or the broader tax system.

It is critical for Australia’s long-term prosperity to undertake meaningful, generational reform. Tinkering around the edges can no longer be the standard. CEDA’s Progress 2050 vision of a strong economy and a stronger social compact requires a reformed tax system to underpin productivity growth and create a more equitable future for the next generation and beyond.

What does the Budget say about the economy?

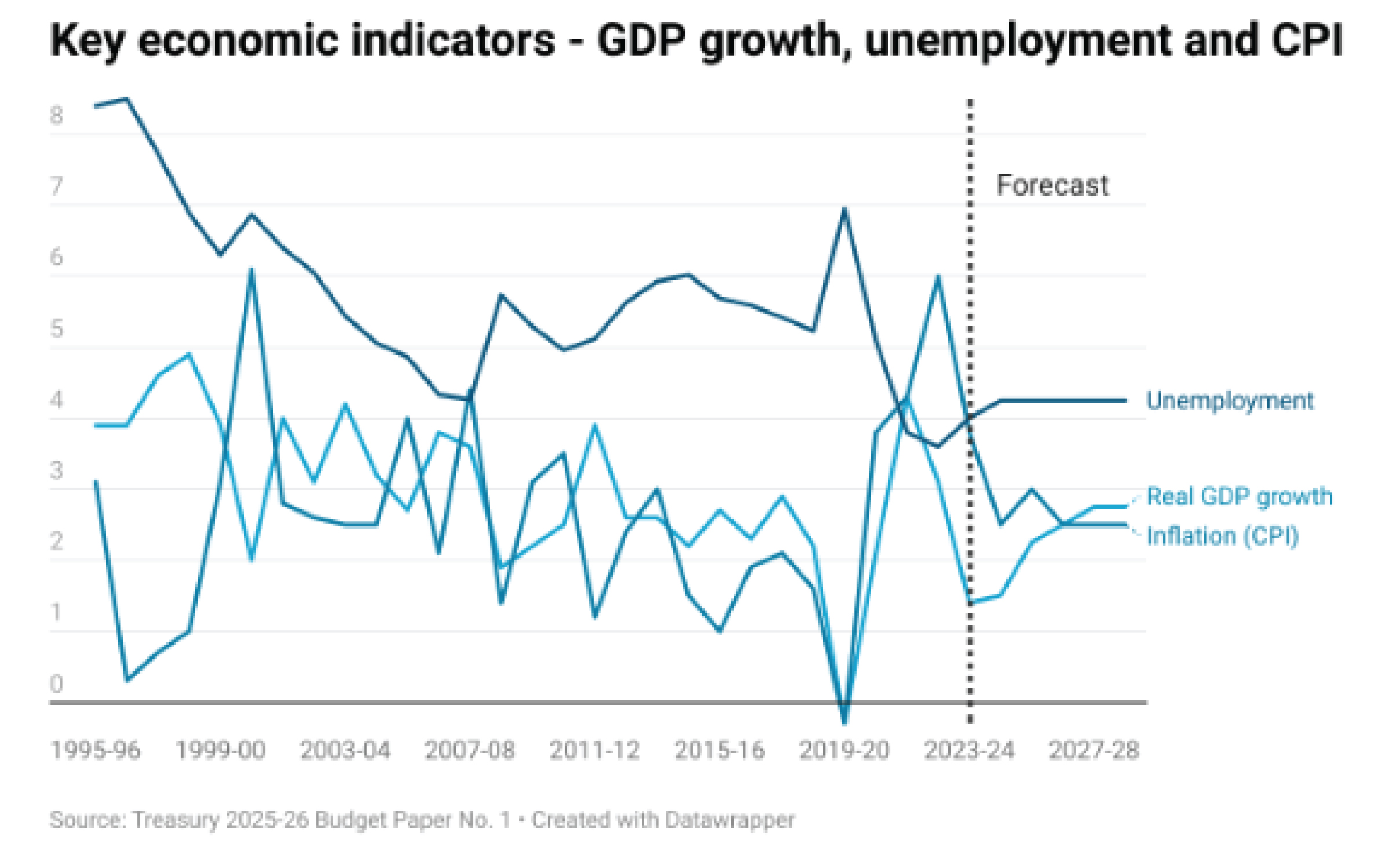

The Budget forecasts real growth to increase from 1.5 per cent in 2024-25 to 2.25 per cent in 2025-26, reaching 2.5 per cent by 2026-27.

Australia’s economic growth could be affected directly by tariffs imposed by the United States, as well as more indirectly, by their broader impact on global growth. The Budget suggests this impact could be relatively minor, as did modelling released by the Reserve Bank earlier this year. But current uncertainty and volatility make the precise impact hard to estimate.

Unemployment remains surprisingly low despite the steady reduction in inflation, but is forecast to increase modestly to 4.25 per cent in 2025-26. Coupled with lower migration forecasts, this points to a still tight labour market.

Inflation returned to the RBA’s target range of 2-3 per cent in 2024-25, but remains an ongoing risk. It is expected to remain in this range over the forward estimates.

What does this budget do for spending?

Total government spending in 2025-26 has been revised upwards by $2.1 billion, mainly through more money to Medicare and cost-of-living relief. This risks further entrenching the long-term structural deficit.

The main spending measures over the forward estimates are:

- Increasing bulk billing for doctors, costing $8.5 billion;

- Increasing pay for childcare and early education workers and guaranteeing three days per week access, costing $5 billion; and

- Electricity bill rebates costing $1.8 billion in 2025.

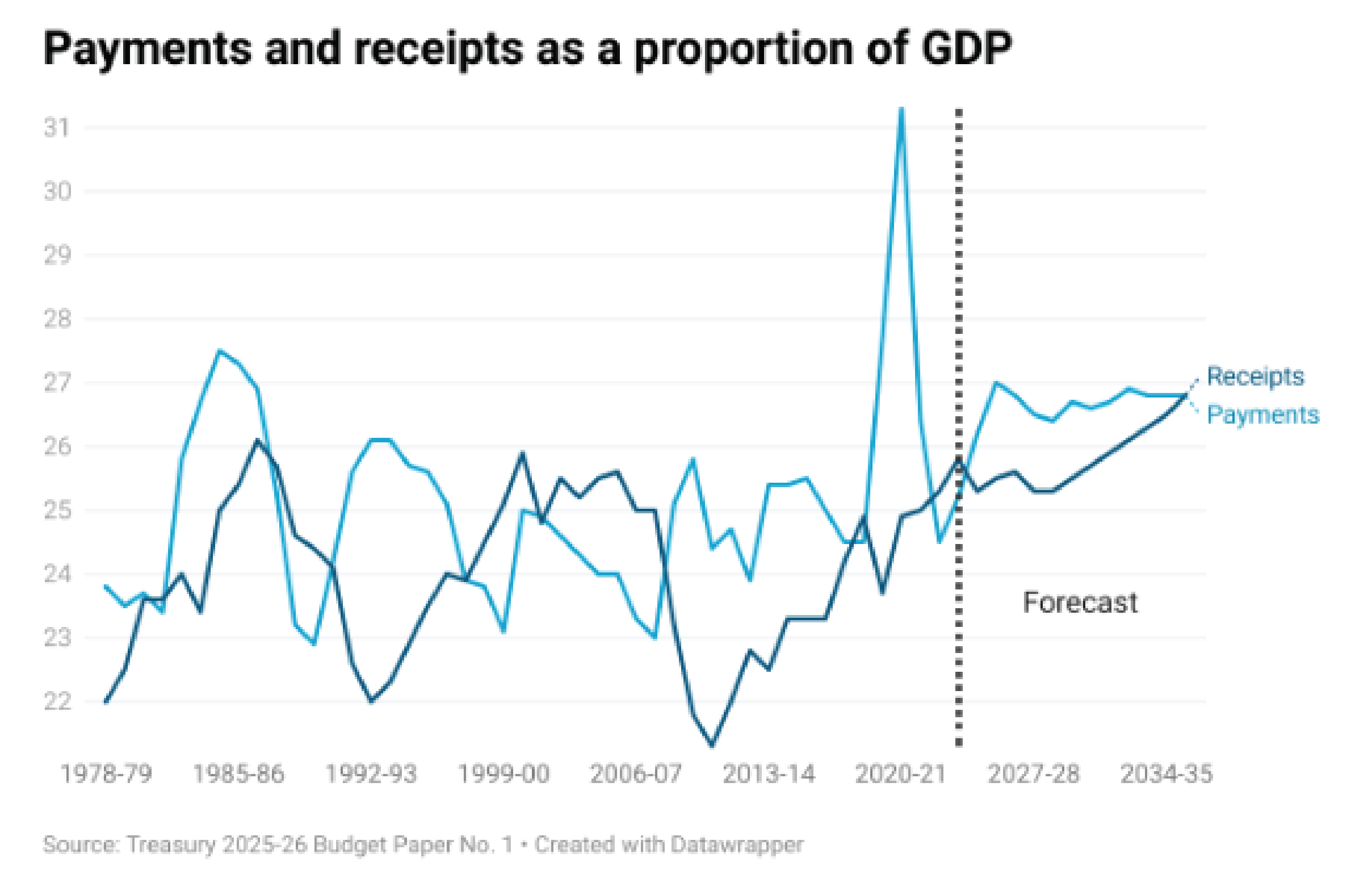

Spending is forecast to reach around 27 per cent of GDP in 2025-26 and to marginally decline over the forward estimates to 26.4 per cent in 2028-29. The Government must exercise restraint in spending, rather than aiming for a specific target. It must also limit any new spending to measures that will actually grow capacity in the economy.

What does this budget do for revenue?

Revenue in 2025-26 is forecast to be $6.9 billion higher than expected in the previous budget update, driven entirely by more favourable conditions, rather than policy decisions. Over the forward estimates, however, revenue has been revised downwards owing mainly to the income tax cuts.

The main revenue impacts in the budget are:

- Lower tobacco excise receipts – downgraded by $6.9 billion over the forward estimates;

- Short-term upward revision of company tax by $4.5 billion in 2025-26, but then downgraded by $1.9 billion over the forward estimates due to lower-than-expected non-mining company profits; and

- Policy decisions decreasing tax revenue – primarily personal income tax cuts – costing $15.1 billion over the forward estimates.

Provided the budget parameters hold, tax revenue is forecast to be around 25.5 per cent of GDP in 2025-26, rising to 25.6 per cent in 2026-27. The volatility of the parameters and overall tax revenue is yet another reason the tax system needs considered and ambitious reform to ensure long-term stability and prosperity.

How does this budget align with Progress 2050?

Earlier this month, CEDA unveiled its Progress 2050 vision, which builds on insights gained from our members, as well as lessons from the economic dashboard we released last year. With the intent of creating a better future for the next generations, our policy goals under Progress 2050 aim to ensure Australia can grow a strong economy to underpin a strong social compact.

Some measures in this Budget support these goals, while others fall short.

A push toward greater productivity through the National Productivity Fund and revisiting the Seamless National Economy agenda will help to build a stronger economy.

Measures to improve housing and access to critical services, such as aged care and education, will require a stronger social compact, however, these measures are more focussed on addressing immediate pressures, rather than the long-term planning required to build a strong social compact.

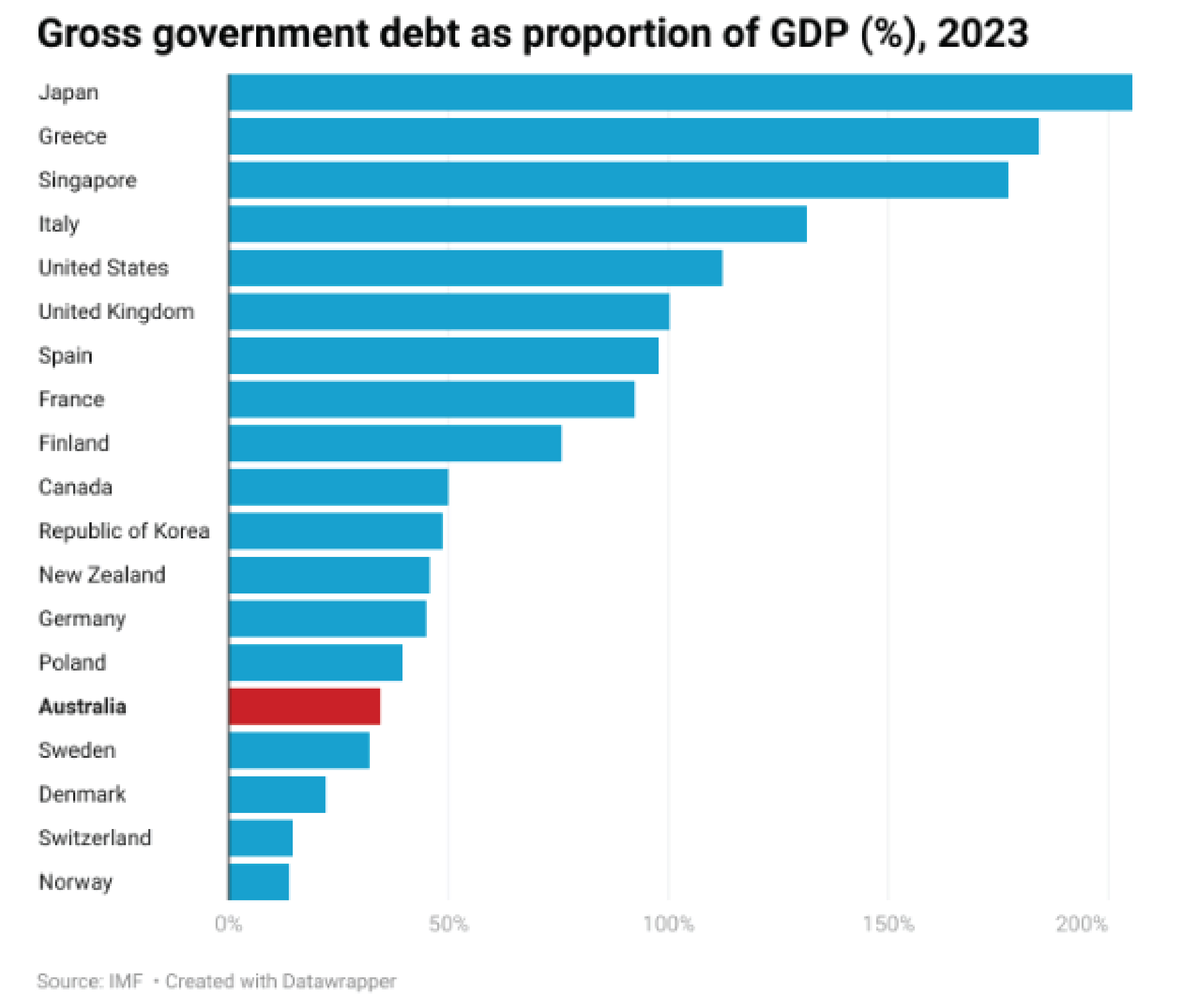

Countries such as Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland have been able to support their strong social compacts through relatively high taxes, including currently or formerly taxing wealth. This has enabled long-term planning for the delivery of social services without creating long-term structural deficits.

Critically, a lack of attention on the longer-term budget position threatens our ability to deliver on crucial services into the future.

What does this budget do for productivity and growth?

The budget does little to address productivity, dynamism or long-term growth. Tax reform must be at the heart of long-term planning to support productivity and prosperity. This is consistent with our Progress 2050 goal for Australia’s businesses to be amongst the most competitive and dynamic in the world. Without a strong, responsive and dynamic economy we may not be able to appropriately respond to the challenges and global uncertainty we are facing.

The previously announced $900 million National Productivity Fund is a good starting point, but needs further action on implementation.

The plan for a national licensing scheme for electrical tradespeople is a much-needed step towards boosting productivity.

CEDA has long argued for reform of Australia’s rigid occupational licensing scheme, as declining labour mobility and workforce shortages are holding back investment and productivity in sectors such as housing construction and energy.

The ban on non-compete clauses, with a focus on low- and middle-income workers, should also help to lift productivity, as it removes a barrier for workers looking to move to jobs that better use their skills. These clauses reduce wage growth and limit job mobility.

But much more needs to be done. A reinvigorated Seamless National Economy agenda would also improve dynamism and promote productivity. It should focus on streamlining regulation; removing duplication across jurisdictions; and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation.

Energy

The extended energy bill relief for all households is poorly targeted and unnecessary following falls in the consumer price of electricity (excluding rebates) in 2024. Universal payments such as these also risk stoking inflation.

The best thing we can do to bring down the cost of living now, and over the longer term, is keep a lid on inflation and get our housing crisis under control.

Australia’s social compact was built on the principle that those who could afford to pay for services would do so. Today, however, many Australians receive a benefit whether they need it or not, and regardless of whether this brings a net benefit.

There is still a lack of detail on Australia’s net zero plan and the Future Made in Australia policy. Both need to seize opportunities where Australia can best contribute to cutting global greenhouse gas emissions, setting the foundation for clean energy exports and incorporating a clear and robust evaluation strategy for transparency and accountability.

Migration

This Budget makes very little mention of migration and there are no new measures to improve our migration settings to boost productivity and fill worker shortages in key industries.

Better long-term planning of the migration system is crucial.

The Government’s Migration Strategy noted that an ‘essential skills visa’ was under consideration to address key workforce challenges. The lack of progress on this remains a concern.

Aged care

Aged care is the fourth-biggest area of Government spending, with annual funding rising to $49 billion annually by 2027-28. This Budget includes little new spending or initiatives, with most of this spending already planned.

The recommendations of the Aged Care Royal Commission are progressing slowly. The sector is still suffering critical shortages of workers and little has been done to make meaningful progress. Without a strong, high quality workforce, quality care cannot be provided. More training packages and better avenues for attracting migrant workers will ensure the sustainability of the sector.

There are ongoing concerns around the sector’s ability to invest in facilities, workforce and technology. It is reasonable that, where they can afford it, older Australians contribute more to their care by paying for daily living costs such as cleaning, food and activities and while there have been some positive developments towards this the longer term funding sustainability still needs attention. The Government should consider including the family home in means testing for aged care. In addition to helping with funding, it would also treat homeowners and renters more equitably.

Ensuring all Australians have access to the care they need to thrive is a key goal of Progress 2050.

Housing

Similarly, the lack of progress toward the recommendations of the Housing Accord is disappointing, and reflects a lack of genuine long-term planning.

More can be done to address the shortages in the short term, including repurposing existing buildings and increased use of modular housing to start to build toward the Accord’s goal of 1.2 million additional homes.

New housing measures in this Budget include an expansion of the already announced Help to Buy scheme to assist Australians to purchase homes, and a modest $54 million to invest in more modern methods of construction. While welcome, they do not address the underlying issues affecting housing supply.

There remain many hurdles to delivering more housing that have not been addressed in this Budget, including planning and zoning regulations and the lack of available construction workforce.