PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

31/07/2012

|

|

Speech delivered by Professor the Hon Stephen Martin at the 7th Annual Skilling Australia and Workforce Participation Summit on Monday 27 August.

Perspectives on competitiveness - is Australia losing the edge?

- Factors driving declining competitiveness and the lowering of labour market performance

- Strategies to rebuild labour market strength

- Does the ongoing restructure of our workforce present an opportunity for recalibration towards strategic, productive and sustainable skilling?

- Investment in skilling - what are key areas for focus

Introduction

Thank you for the opportunity to be with you today.

CEDA has a long and distinguished history of thought leadership in framing the economic issues that affect Australia. In particular we have taken a keen interest in the interconnection between productivity and competitiveness and what define these, with a significant emphasis on education and workforce skilling.

While some recent statistics for GDP growth and employment paint a picture of an economy on steroids, there are some lingering questions about macro and micro measures of the economy's health and the current and future contribution of various sectors to the nation's long-term economic sustainability. These questions go directly to the issues confronting this conference- and will help shape the very nature of Australia's future economy.

Australia in August 2012 is a very interesting place. Much is still being heard about a two-speed or multi-speed economy. Retailers have complained the loudest, although the latest figures for May and June would indicate shoppers have returned on the back of interest rate cuts and government carbon compensation. There are also signs that the expected skills shortages in the mining industry have not materialised, or at least are being appropriately managed.

Genuine concerns however have been voiced by tourism operators and manufacturing industry about their economic viability, no more so than in Victoria where fundamental structural adjustment is occurring at a substantial pace. Wealth generation, despite some pessimism as to its sustainability, is very much centred in the mining industry that employs about seven per cent of the workforce.

The international environment is also a significant influence. Europe's woes, uncertainty about the United States' economy and concerns about China's economic future are all considerations in how Australia's competitive advantage and productivity challenge may play out in the coming years.

So what effect then are the twin determinants of prosperity- productivity and competitiveness- having on Australia's current economic circumstances, and what can we assume will be the future? What strategies are needed to rebuild labour market strength and to invest in skilling and education as critical contributors to lifting Australia's competitiveness and productivity?

Productivity

Productivity is the current buzzword used in the media and elsewhere to describe everything that is wrong with Australia's economic performance.

Some use it for shorthand to describe what it considered the real bogey of the current Australian economy- industrial relations, or more precisely, the Fair Work Act 2009.

But when we speak of productivity it is far more than that.

Reserve Bank of Australia defines it as the efficiency with which an economy employs resources to produce economic output.

Economist Saul Eslake says productivity is what a workplace, a business … or a nation gets by way of goods and services for what it puts in, in terms of labour, capital and other factors of production.

US economist Paul Krugman (1994) said:

''Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run, it's almost everything. A country's ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.''

The most widely discussed link between national prosperity and regulatory arrangements in the labour market is through productivity [1]. There are other important links between the labour market, its regulatory arrangements and national prosperity. These include the overall growth rate of wages (which influences consumer price inflation), the response of wages to changes in demand for and supply of labour, the amount of industrial disputation and time lost associated with disputes, the regulatory burden imposed on employers, and the level of employment and participation in the workforce.

It is now widely recognised that growth in Australian labour productivity-output per hour worked-has slowed since the late 1990s, notwithstanding stronger data in the past few quarters. Labour productivity growth explained less than half of the growth in average incomes since the turn of the century, compared to an average of around 90 per cent of income growth over the four previous decades.

Multifactor productivity-the output produced from a bundle of labour and capital inputs-has scarcely grown at all this decade. While the deterioration in performance is partly due to unusual developments in mining and utilities, the slowdown from the 1990s is broadly evident across most industries [2].

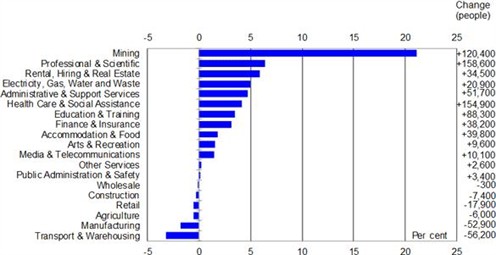

Labour market trends show this bifurcation in growth. Over the three years since May 2009, employment in agriculture, manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade, and transport, postal and warehousing services has fallen by a combined 140,700 people. At the same time, employment in the rest of the economy increased by 733,000 people, with the mining sector alone accounting for 120,400 jobs. Most households that have lost jobs are finding new ones and benefiting from the mining boom.

Interestingly, it is the mining industry itself that is the chief culprit for the productivity decline, because the hundreds of billions the sector has been investing in new projects are yet to result in output [3].

Employment growth by industry - May 2009 to May 2012

Annual average percentage change

Source: Treasury calculations based on ABS cat. no. 6291.0.55.003.

Competitiveness

The notion of Australia being competitive in a global context is one of the most critical unresolved issues facing industry, governments and policy makers.

World Economic Forum (WEF) defines competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of a country's prosperity. Productivity level also determines the rates of return obtained by investments in an economy, which in turn are the fundamental drivers of its growth rates. In other words, a more competitive economy is one that is likely to grow faster over time [4].

WEF notes there are many determinants driving productivity and competitiveness- including education and training, technological progress, macroeconomic stability, good governance, firm sophistication, and market efficiency.

Using its 12 measures of competitiveness Australia dropped four spots to 20th place in its latest survey. It found Australia's most notable advantages are:

- Efficient financial system, supported by a banking sector that counts among the most stable and sound in the world performance in education;

- Macroeconomic situation;

- Low government debt; and

- Transparent and efficient public and private institutions, physical security.

While Australia's disadvantages are:

- Burden of government regulation;

- Innovation;

- Business sophistication; and

- Infrastructure.

In late May, the findings of the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook, an annual survey of world competitiveness that ranks 59 countries on their ability to manage their economic and human resources to increase their prosperity were released [5]. CEDA is the Australian partner for this survey.

This year's report painted an alarming picture of a first world economy that was slipping in many of the measures of competitiveness. Australia's ranking of 15 out of 59 countries represented a drop of 10 places in two years. Australia has been overtaken by Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, Denmark, Malaysia and Luxembourg.

Big drops in labour market and international trade competitiveness were suggested as the key contributors to our slide.

For labour market competitiveness significant reasons contributing to Australia's poor ranking included the high Australian dollar, skills shortages and the re-emergence of industrial relations as a key national issue, highlighting the increase in the number of high profile disputes in the Australian economy.

While economists and policy-makers have acknowledged for some time the negative impact of the high dollar on sectors such as manufacturing and tourism the reality is Australia is likely to see more manufacturing production move overseas where production and labour costs are lower.

Australia is unlikely to compete with emerging and developing economies in the production of low-cost, large scale manufacturing, particularly in our own neighbourhood. Indeed, as we are constantly reminded, Australia is a high wage, high skill economy, and structural adjustments are required to meet the challenges that this brings.

What was also clearly highlighted in this report was that we cannot rely on the mining boom to insulate Australia from the current global economic slowdown.

Yet Governments and some economic commentators seem to believe that the mining boom will go on indefinitely regardless of evidence of slowing commodity prices and demand from traditional markets, skill shortages and regulatory instability and barriers.

The reality is the increasing cost of doing business in Australia is beginning to impact this sector, with commitment to major projects being reassessed or deferred. BHP-Billiton's deferment of Olympic Dam in South Australia is a case in point.

These same economists and policy-makers assume that the current elevated terms of trade will return to more normal conditions while business investment will continue for several years to support GDP. However many of these assumptions are based on Australia's continuing trade relationships with our Asian neighbours, specifically in commodities, and the view that these will continue at current levels.

Obviously a key factor to consider is the sustainability of China's growth and whether a rapid decline in demand for Australia's resources may occur if there is a drop in China's economic activity.

It is critical to note in this respect that the actions of other resource-rich nations, particularly in Africa are also relevant. While Australia has a first mover advantage in exploiting resources, in the medium term the exploration and investment underway elsewhere will have a major influence on the terms of trade and the willingness of business to continue high-level investment in Australia. If Australia becomes a high cost investment destination, with regulatory uncertainty, it may price itself out of future business investment.

Commentary around how to resolve these and other issues, particularly whether Australia should continue to sustain non-competitive industry sectors, is caught up only in an argument about subsidies and employment support in marginal electorates.

I would argue that Government should only intervene with subsidies for any sectors where a clear strategic imperative can be demonstrated. Instead their focus should be on reducing regulatory burdens to allow businesses to become more competitive, and invest in skills allowing businesses with long-term viability to make the necessary adjustments to survive the current changes in our economy.

A second major report with respect to competitiveness that received some emphasis in the conservative media was the Economist Intelligence Unit's Global Index of Workplace Performance and Flexibility, released in early July. It ranked 51 nations on how each was seen as a place to operate a business productively, fairly and flexibly supported by three sub-index rankings in the fields of economic performance, operating environment, and workplace policy and regulatory framework [6].

Australia's operating environment ranked 8th best in the world, but our policy and regulatory framework placed down at number 19. Economic performance ranked at 34 highlighting Australia's stuttering productivity record over the last 10 years relative to our global competitors. It was concluded that in a globalised competitive world Australia's regulatory framework stands out as overly restrictive and conducive neither to optimal performance nor social equity.

It should be noted however that this report relied on data from 2010, and many of its observations were very much skewed to consideration of workplace relations changes that were considered necessary to achieve flexibility.

Innovation

Innovation is perceived by many as the panacea for an economy's ills. Be innovative, jobs will come and the economy will flourish.

A joint Productivity Commission-ABS report concluded that Australian firms appear more likely to innovate if they face stronger competition. The results suggested that innovation is associated with better productivity outcomes [7].

Australians have always been innovative. From the boomerang to the black box flight recorder, underwater torpedo, ultrasound, bionic ear, electronic pacemaker, spray-on artificial skin to Vegemite.

Yet the traditional definition of innovation is what most would believe. That is, applying some new scientific principle or improved manufacturing process to an existing industry sector to get a better product or outcome.

It is however much more than that [8].

"Innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), process, new marketing method or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations". Oslo Manual

"Research and experimental development (R&D) comprise creative work undertaken on a systematic basis in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this stock of knowledge to devise new applications." Frascati Manual

The Milken Innovation Report [9] undertook a global analysis of the innovation environment in 22 countries and assessed country performance across seven innovation indicators. What it concluded was that Australia was a leading nation for innovation in university-industry collaboration, R&D expenditure, patents, STEM education and business environment, and Above Average in venture capital deals and technology exports.

The Report concluded that innovation was the main lever for a more competitive economy and the best way to create jobs. Further, it was found that the sectors of energy, healthcare and telecommunications would benefit most in terms of job creation and increased profits if governments implemented more efficient innovation policies. It concluded that innovation would be driven by SME's and a combination of players (industry, government, universities) partnering together over the next decade.

However, the World Competitiveness Yearbook survey referred to earlier sounded a note of caution, indicating a lack of global competition and a relatively stable economy has created a complacent society and has not provided any incentive for business to innovate. In part this has contributed to our productivity slowdown and must be addressed as a matter of urgency.

Skilling and education

When discussing productivity and competiveness, the third of the three amigos steps up- skilling and education.

The Federal Government has a critical role in this area. It has committed some $3 billion over six years to improve the skills of Australia's workforce through reforms to the vocational education and training system, delivering industry-focused training, developing innovative approaches to support apprentices and trainees, and encouraging workforce participation. The National Broadband Network should also enhance productivity with education and skilling benefits.

But education and training must obviously be linked to meeting Australia's skills requirements, with implications for the current and future labour market. The 2012 National Workforce Development Strategy [10] seeks to do this. It makes some interesting observations which touch on the key issues for policy development:

- Skills shortages in some areas and industries threaten wage inflation and risk growth-constraining monetary tightening;

- There are pockets of high unemployment across Australia's regions, especially among young people; and

- There is also scope for improving leadership and management skills to bolster innovative capacity.

In seeking to predict employment and skills needs to 2025, four scenarios are developed for Australia.

These confirm demand for high levels of skills can be expected to continue into the future in response to technology-induced change, structural adjustment, a progressive shift to services-based industries, Australia's changing demographics and increasing globalisation with Asia a burgeoning market for Australian services.

The discussion paper also indicates that it is important that a shift to higher skills does not leave the low-skilled and unskilled behind. Strategies are needed to help disadvantaged groups gain skills and employment, including better matching of human capital with those regions and industries in need. Entry-level positions are needed for those waiting to get a foothold on the employment ladder.

There is no doubt that the role of the tertiary education sector is critical in meeting these challenges. Issues concerning the mix between theoretical and practical skills, developing jobs-ready graduates, the impact of demand-led higher education and vocational education and training (VET), fostering STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) subjects for Australia's future competitiveness in the global marketplace and keeping pace in the Asian century require appropriate policy settings.

A current issue however that needs a more rapid policy response goes to national skill shortages, particularly in the face of falling immigration and rising retirement. Deloitte has examined this with respect to the positive actions business and government can take [11].

Table 1 Deloitte 12 Levers of Economic Prosperity

|

Population |

Lever 1 |

Your next worker is still being educated |

|

|

Lever 2 |

Your next worker is in the crowd |

|

|

Lever 3 |

Your next worker is overseas |

|

|

Lever 4 |

Your next worker is waiting for a visa |

|

Participation |

Lever 5 |

Your next worker is retired - or about to retire |

|

|

Lever 6 |

Your next worker is juggling work and family |

|

|

Lever 7 |

Your next worker has the ability |

|

|

Lever 8 |

Your next worker is interstate |

|

Productivity |

Lever 9 |

Your next worker is not needed |

|

|

Lever 10 |

Your next worker is in the mail room |

|

|

Lever 11 |

Your next worker is knocking on your door |

|

|

Lever 12 |

Your next worker may currently be on cruise control |

It noted that the problem in Australia in coming years won't be a lack of jobs - it will be a lack of workers. Businesses need to recognise that in the future:

• Competition will be for workers rather than jobs;

• An employee already working for you will be more valuable than someone new; and

• Allowing an employee to retire without exploring the options to keep them for longer may represent a wasted (and costly) opportunity.

Deloitte's paper noted that Dr Ken Henry outlined three supply-side contributors to economic growth known as the 'Three Ps': population, participation and productivity [12] and went on to suggest there were 12 levers which business and government can use to solve skills problems and boost growth prospects.

The fact is that education and training is critical to ensuring an appropriately-skilled workforce is available to meet the current and future requirements of Australia's economy. Investment in these by governments and business must be coordinated, incentives provided and clear strategies adopted that deliver meaningful outcomes. They will ultimately be measured by improving productivity, our ability to respond to global competitiveness and our economic sustainability.

Australia's opportunities

This then brings us to consider what this means in terms of opportunities for Australia.

Clearly there are some lingering questions about Australia's ability to rise to the challenge of improving competitiveness and productivity as well as the current and future contribution of various sectors to the nation's long-term economic sustainability.

There are also implications with respect to what jobs will be needed in the future, what skilling needs to occur to ensure sustainability and productivity and what are the implications for policy makers in achieving these desired outcomes.

In my view it comes down to the right reform agenda that is comprehensive and inclusive with education and skilling as one of its core determinants.

CEDA's Council on Economic Policy has noted that Australia would only need to improve productivity growth to around 1.5 per cent per annum, although still low in historical norms, to potentially underpin robust economic growth for the next decade.

Australia's current economic prosperity has been supported by past policies that have focused the nation on its international competitive advantage, including innovation and educational up-skilling, and that focus needs to be reinvigorated. But it must be targeted.

In the 1990s Australia was a leader in business innovation but unfortunately this is no longer the case. A lack of global competition and a relatively stable economy has created a complacent society and has not provided any incentive for business to innovate. In part this has contributed to our productivity slowdown.

Increased investment in skills, in particular science, research and technical skills, would allow us to be a leader in high value, high-tech manufacturing and in resource extraction and development, increasing our ability to deliver high value product.

And of course it is the services sector that needs careful strategic support from governments to take advantage of opportunities being presented through the current phase of industrial restructuring.

Continued technological advances are expanding what constitutes tradable goods and services. While this represents a potential opportunity for a highly educated nation such as Australia, it also represents a potential challenge to sectors of the economy that have not been globally integrated or exposed to international competitive pressures in the past. These include significant parts of the services sector.

Mining engineering, IT, legal, accounting, high-value manufacturing, health and education services are but some of the components of the future wave of employment generating and export-oriented opportunities that must be exploited.

However, a significant risk for Australia is that jobs growth in the future will be determined by these sectors that have historically not exhibited high levels of productivity growth.

In particular, the fact that the National Competition Policy reforms of the past largely ignored the major services sectors may mean Australia's economy is not as well positioned to adjust to changes in those areas as it should be.

With the mining boom taking the spotlight in recent years, it is easy to forget that the services sector provides 80 per cent of Australia's employment and when the resource-related investment diminishes, as is likely at some stage, future employment opportunities will most likely continue to predominantly be in these sectors.

Some of these sectors are not as productive, at least not as measured by official statistics, as other areas of the economy and the ability of them to lift productivity - of which their ability to innovate will be a key factor - is vital.

While expenditure to drive innovation has gradually increased in the last decade, mostly in the mining and resources sector, growth in investment by business in many of the key services sectors is minimal.

Conclusion

Australia's current economic prosperity owes much to the sweeping economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, the minerals boom and associated investments and fiscal and monetary policy working in tandem to secure Australia's resilience in the face of global uncertainty.

However, the large employing sectors of health and education were not a focus of those reforms and have had only limited focus in terms of productivity since. Yet it is precisely in these areas that major innovation should have occurred. Rather intergovernmental squabbles over responsibility, funding arrangements and commercialising research have dominated.

With an ageing Australian population and improving prosperity in Asian nations, it is more important than ever that these sectors are exposed to meaningful reform to enhance their effectiveness and capacity for innovation. Export opportunities are expected to be robust, but only if their potential is realised through an appropriate policy mix.

We need reforms that focus on building competitive capability to ensure they are better equipped to adjust - and innovate - as future competitive pressures evolve. Reforms that focus on building competitive capability, through reviews of areas such as the tax system, workplace relations, regulatory frameworks and public spending are essential.

Increased investment in skills, in particular science, research and technical skills, is also a vital component, and would allow us to be a leader in high value, high-tech product and knowledge.

Developing a long-term skills plan for Australia is a vital component in making sure that we can capitalise on growth sectors that can and will contribute to Australia's future prosperity. But the policy must ensure the future of work is the driving force behind this.

Achieving the changes necessary cannot simply fall to government to determine and implement.

The private sector needs to step up as well and invest far more in innovation, research and development, improving productive capacity through new business systems and cooperative working relations and not simply put their collective hands out for government subsidies.

Recognition of the need for vital economic change helped drive public acceptance of the sweeping reforms of the 80s and 90s. These have been key factors in protecting Australia from the international economic turmoil of recent years. The current economic climate provides a real opportunity to again drive a reform agenda with a long-term vision, but it must be driven in unison by both government and business.

|

|

[1] Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2012) Review of the Fair Work Act 2009, Canberra

[2] Dolman, B and Gruen, D (2012) Productivity and Structural Change Paper presented to 41st Australian Conference of Economists, Melbourne, 10 July.

[4] World Economic Forum (2012) 2011-12 World Competitiveness Report, WEF, Geneva

[5] IMD (2012) World Competitiveness Yearbook, 24th Edition, Lausanne.

[6] Economist Intelligence Unit (2012) Global Index of Workplace Performance and Flexibility, July

[7] Productivity Commission-ABS (2011) Competition, Innovation and Productivity in Australian Businesses

http://www.pc.gov.au/research/collaboration/business-innovation

[8] Gelb, David (2012) Research and Development and Innovation Presentation to CEDA Forum, Sydney, 6 July 2012

[9] http://www.ge.com/au/docs/1326856679242_Milken_Innovation_Report_-_Australia_Key_Findings.pdf

[10] Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency (2012) Future Focus: Australia's skills and workforce development needs Discussion paper, July, Canberra

[11] Deloitte Australia (2011) Building the Lucky Country: Where is Your Next Worker?

[12] Henry, Ken (2003) Economic prospects and policy challenges, Address to the Australian Business Economists, Sydney, 20 May http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/639/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=speach_%20main.asp

References

Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency (2012) Future Focus: Australia's skills and workforce development needs Discussion paper, July, Canberra

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2012) Review of the Fair Work Act 2009, Canberra

Deloitte Australia (2011) Building the Lucky Country: Where is Your Next Worker?

Dolman, B and Gruen, D (2012) Productivity and Structural Change Paper presented to 41st Australian Conference of Economists, Melbourne, 10 July.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2012) Global Index of Workplace Performance and Flexibility, July

Gelb, David (2012) Research and Development and Innovation Presentation to CEDA Forum, Sydney, 6 July 2012

Henry, Ken (2003) Economic prospects and policy challenges, Address to the Australian Business Economists, Sydney, 20 May

http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/639/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=speach_%20main.asp

IMD (2012) World Competitiveness Yearbook, 24th Edition, Lausanne

Milken Institute (2012) Innovation Report

http://www.ge.com/au/docs/1326856679242_Milken_Innovation_Report_-_Australia_Key_Findings.pdf

Productivity Commission-ABS (2011) Competition, Innovation and Productivity in Australian Businesses

http://www.pc.gov.au/research/collaboration/business-innovation

Stevens, Glenn (2012) The Lucky Country, Address to The Anika Foundation Luncheon, Sydney, 24 July

World Economic Forum (2012) 2011-12 World Competitiveness Report, WEF, Geneva