PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

05/07/2023

It’s great to be here talking about my favourite topic, the economics of the aged-care workforce. I’m the Chief Economist of CEDA, which is the Committee for Economic Development of Australia. Our purpose is to improve the lives of Australians by enabling a dynamic economy and a vibrant society.

For some time now, aged care and the care economy more broadly has been one of our key research focuses because it’s so clearly linked to this purpose. I think it’s such an important sector and one that is often viewed as a cost to the economy – we talk about how much it’s costing the Budget, we talk about all the demand coming and how expensive that’s going to be.

But what we should really be talking about is the aged-care sector as an economic growth area. This is going to employ a lot of people and I’m going to talk about the challenges of that today, but that’s actually a good news story – we want people in jobs. It’s going to drive a lot of economic growth and we need to keep that in mind when we’re talking about these things. Yes, we have challenges, but it’s a growth sector and it’s one that is contributing to the prosperity of Australia.

Whenever I give a talk on aged-care workforce issues, I always start with this quote from the Royal Commission because I think it is just absolutely key to everything that we’re trying to achieve in aged care.

“The evidence is clear that the quality of care and the quality of jobs in aged care are inextricably linked.”

We can talk as much and have as many plans as we want to increase the quality of care, to change things up, to transform the sector. We can’t do that without the size of the workforce that we need and the quality of workforce that we need. And we’re not there yet.

To meet any of the strategies, or visions, that we have for a really high-quality, high-performing aged-care sector that is going to contribute to our society and give older Australians the care that they deserve and that we as a community want to give them, we can’t do that without more workers. This is really challenging to achieve and we are not achieving it yet.

There’s a short-term challenge, and we’ve got a particular crunch point at the moment, but there’s a really long-term challenge coming here for aged care.

With the demographic change and the ageing of the Australian population, we are only just starting to see the tip of that coming through in the demand for care. There’s a lot more to come there, and even at the moment we still have a lot of unmet demand for care. There’s a lot of demand that is not being met, particularly in the home-care space, but also in residential, and that is again a really big challenge.

We still have very high rates of turnover in the sector. We have the coming changes to increase staffing minutes, the first tranche of that is pretty soon and the changes around requiring 24/7 registered nurses. This is all in an environment where we have a lot of constraints on the supply of workers.

Wages are still relatively low, and there are challenges around working hours and getting staff the rosters that they want. Career progression is slow. Training and qualifications are probably still not quite up to scratch.

Concerns around the perceptions of the industry, Geraldine mentioned the impacts that bad media stories had in the foster-care industry, and I think it is very clear that we have that same challenge in aged care. I think the perception is very different to the reality of what working in aged care is.

Long-term worker shortages

Particularly at the moment, we have labour shortages across the economy. That’s quite acute now, but if we look at the demand even in the coming decades for labour around the world, we are going into a period of long-term labour shortages, so this is not going to get easier anytime soon.

I’m going to start talking about the long term, so out to 2050, and then I’m going to come back and talk a little bit more about the challenges and what we’re seeing in the market at the moment.

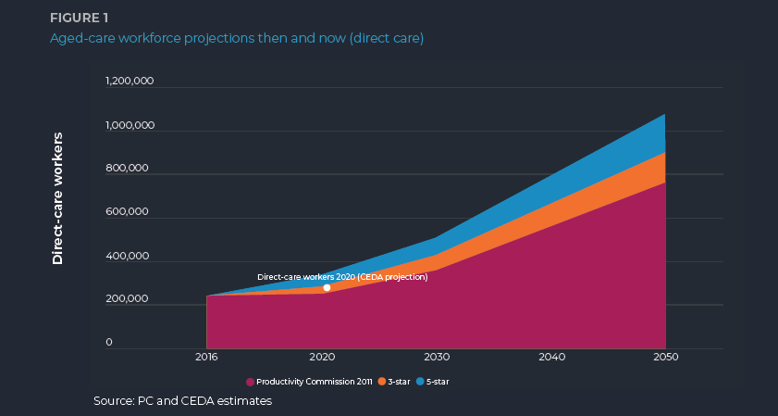

This is some work that CEDA did in 2020, forecasting out demand through to 2050 and really looking at how that might fit with increases in staffing and what we want to see. We have the baseline projections there at the bottom adding on about a 20 per cent uplift in workers to get to that baseline, so that 200 staffing minutes a day and then a further projection on top of that, which is a 50 per cent uplift from the baseline. These are pretty stark numbers. We’re looking at well over a million workers by 2050 and we’re sitting at somewhere around the 300,000 mark now, so that’s huge.

.png)

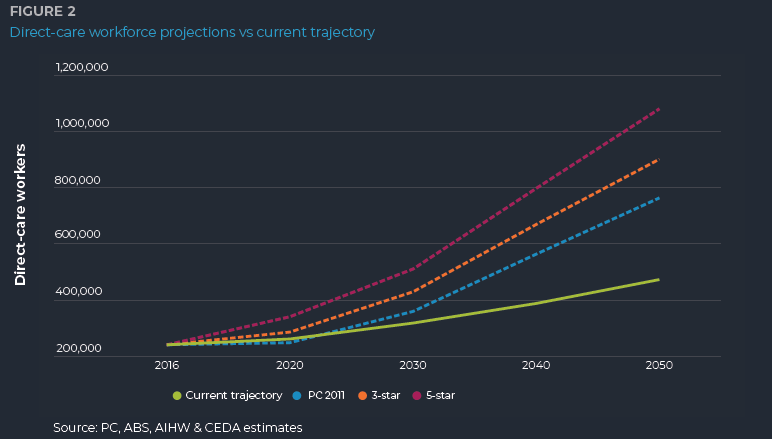

What probably makes it even starker, is when we look at the recent trajectory of growth in the aged-care sector. One thing that’s really challenging as an economist is the data on how many workers are in the sector is not great to come by, it’s not updated very often, and it’s not as comprehensive as we would like, so it is quite difficult to work out exactly where we’re standing on workforce numbers and growth. But we’ve looked at a number of different data sources and we think that roughly over the past few years, the aged-care workforce has been growing at something like two per cent per annum. That is not enough.

If we kept growing at two per cent per annum by 2050, we would have a shortage of 400,000 workers. If you think about the impact that that would have on the care that you can provide people, that’s really dramatic.

But still, 2050 might seem a long way away. If we look at 2030, if we continue on at this pretty slow rate of growth, that’s still a gap of 110,000 workers, so there is still a lot to come in this aged-care workforce challenge.

What we need to see to start to meet some of those goals around the workforce is a doubling in the rate of workforce growth, so that would be increasing to at least four per cent per annum. There are no signs that we are turning that way, so that is a real concern both for the short term and into the longer term.

Short-term challenges

I did some work last year looking at what the shorter-term crunch was, so moving away from these issues over the coming decades and looking at just where we were sitting in 2022. That was because I’ve been talking a lot to people in the industry and they were continually telling me that things were getting worse, which is not what we wanted to hear.

Particularly then and I’m not sure that there’s been a lot of change, but there’s a lot of discussion around increased attrition, bushfires, particularly over east. We’re having issues with fatigue coming out of the COVID period, which I think is still a factor. Burnout and the ongoing issues around understaffing, and you get in these vicious cycles with understaffing and it puts pressure on your existing staff and again makes it more difficult. Very limited movement on paying conditions at that stage in 2022, we probably have seen some improvement here. There were still very low levels of migration trickling back in with our borders opening.

Last year we were saying just in that single year we were down around 35,000 workers. I haven’t updated the numbers in detail for this year. I don’t think it’s much different. I think we have seen a few little improvements, but I don’t think we’ve seen any real change in the trajectory.

What has changed in 2023? When I talk to the sector, I do think there is some progress towards that increased care-minute requirement, but still a way to go and it’s taking a lot of effort. The amount of management effort that it is taking to just sustain the current workforce and then to recruit additional workers on top is a really big cost for the industry and that is a challenge.

The external environment for getting staff and what’s going on in the economy is adding to these pressures. We’ve got rising inflation and cost-of-living pressures. We know that they’re hitting lower-income households far worse than the rest of the community and most of our aged-care workforce is sitting in that lower income threshold. Your workers are almost certainly facing a lot of challenges there.

The labour market is extremely tight and I really can’t emphasise how low the unemployment rate is at the moment. It’s 3.5 per cent. If you had asked me a few years ago, would we see unemployment with a three in front of it, I would have laughed at you. It seems so fanciful that we would get unemployment with a three in front of it and stay there for a significant period of time.

Job vacancies across the economy, across all sectors are really high. We had some new job-vacancy figures out from the ABS today, for those of you that are based here in WA it will be probably unfortunate to hear that actually job vacancies in WA rose while they fell in the rest of the country. There is demand across all sectors and that is what you’re competing with. And you’re particularly competing with adjacent sectors such as disability, health that are looking for a similar skill set, similar personal attributes, but that have that ability to pay slightly higher wages.

We have seen some improvement in migration, so there’s the return of international students and working holidaymakers. But really if we think about the huge quantum of workers that we need, it’s probably not enough there. We are not competitive from a migration standpoint.

This challenge that I’m outlining for Australia is actually very similar to what the UK is dealing with, what Canada is dealing with, what really any developed country is dealing with due to the demographic changes in their countries.

Our migration settings are really difficult. We take a long time to process visas and we don’t have a lot of really good visa categories, particularly for lower-skilled workers. We do have some good options for registered nurses, so we’re really not competitive there and we do need to make some changes to our migration settings to ensure that we get the right workers.

What impact is this external environment having on the sector? The wage increase to come is a positive for workers and probably gives that little bit of that light at the end of the tunnel, but it’s probably not enough as well. Now, I’ll touch on that in a moment.

I am hearing that there’s some improvement in turnover rates with a lot of effort from providers in terms of focusing on retaining those existing staff and having some success, but the amount of effort required on that’s huge.

The other positive that I’m hearing pretty consistently is that staff are willing to work additional hours and that’s probably linked to those cost-of-living concerns. They really are much keener to pick up an extra shift or increase the hours, so that you are getting a bit better utilisation of the existing workforce and that does seem to be a bit of a trend. Again, it’s hard to see this in the data, but from talking to the sector, from a bit more casual to a more permanent workforce, which does have some benefits.

I just want to touch on wages, and I don’t want to labour the point around wages because it’s not the only thing that we need to deal with, and it’s not the solution to all the challenges in the aged-care workforce.

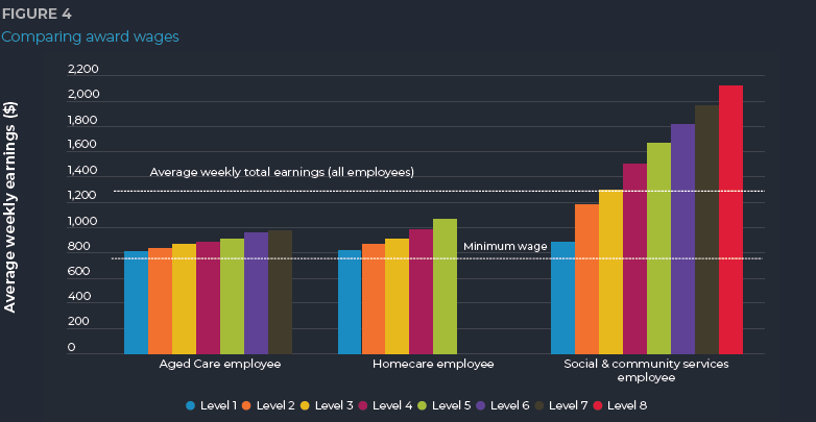

We’ve got this 15 per cent increase in wages coming, it’s still not very significant in terms of when we’re looking at what the wages are and how they compare to other industries.

If we look at the aged-care employees and residential aged care or home-care employees and compare them to the ones on the right, which would be what disability service employees would be under, even before the pay increases, but even if we add that on top, there’s still a big gap there. It’s around more of a 25 to 30 per cent gap between the aged-care sector and the disability sector for a personal care worker with Cert III same qualifications.

Unless we can reduce that gap, that is always going to be a challenge to recruiting staff because you’re looking for the same pool of work.

The other real issue I think we have with wages, which hasn’t been addressed yet, is the lack of progression in wages. There’s barely any change from a level one as you go up. What is the incentive for your staff to invest in additional training or take on managerial responsibilities when there’s very little pay rise to go with it? That again is a real challenge that needs to be addressed.

There is a lot going on in the policy environment, particularly with the new government. Clearly, aged care is on the political agenda, but so far we seem to be having a lot of inquiries, a lot of talk and not so much action.

This is just a snippet of some of the policy strategies and other things going on that are impacting the aged-care sector.

- Productivity Inquiry – released March 2023

- Strategy for the Care and Support Economy – in consultation

- Release of Migration Review – Migration Strategy due late 2023

- Employment white paper – due September 2023

- Aged Care Taskforce

I'm sure there's more that I haven't put up here, but we have the productivity inquiry, which was released in March, which talked quite a lot about aged care. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is developing the strategy for the care and support economy now, it's in consultation if anyone hasn't had a look at that, you might want to jump online and have a look at that.

The migration review was released earlier this year, which again did talk quite specifically about aged care and care workers, and we're expecting a migration strategy later this year.

The Employment White Paper, which is coming out of the Jobs and Skills Summit that was held late last year, is due in September this year and that is likely to touch on aged care. And we also have the Aged Care Taskforce. Certainly a lot of talk, but not a lot that's really addressing current concerns.

Conditions in Western Australia

I’m going to focus in a little bit more on WA now and what are some of the real pressure points that are particularly happening in WA. The kind of things that we're seeing when we talk to those in the industry is that we are seeing some residential facilities not operating at full capacity because they can't get the right workforce in order to do that, so it's not due to lack of demand for the facilities, but it's lack of supply of workers. This is particularly an issue in regional and remote areas, and I'm going to touch on some of the reasons why that is in a second.

There have been some well-publicised closures of some homes, particularly the smaller ones that are struggling to meet the 24/7 registered nurse requirement and a large reliance on agency staff to fill gaps in the workforce, which is adding to the financial pressures on the industry. It's a very expensive way to get your workforce up, and the sector is already not making much money, if any at all.

As I've mentioned before, retaining and attracting the workforce is taking up significant management time when you're also trying to deal with huge amounts of regulatory changes and other day-to-day issues. That's a real challenge, and that is impacting on the industry.

I'm going to talk a little bit about the regions and why I think there are some particular pressures in regional areas. I have two great policy loves, which are both aged care and housing, and I think the interaction between the two of them is what's causing some of the workforce challenges, particularly in regional areas.

These are just some examples of what the median weekly rent is like in some of our regional areas. In the Goldfields or in the South West, where the cheaper regional areas are, you're looking at around $550 a week in rent. In the Kimberley or the Pilbara, when you're competing with a lot of the resources sector, you're looking at $900 to $1,000 a week in rent. That is absolutely huge. If we compare that to what an aged-care worker, or a personal-care worker, might be getting paid, which might be just over $900 a week, you can see pretty clearly why it might be really difficult to attract someone to a regional area.

What we'd usually consider a comfortable rental would be less than 30 per cent of your income going on rent. Even in our cheaper areas, you're looking at more than 50 per cent of a standard wage going on rent, and in the very high-cost regional areas, that’s close to 100 per cent. It's a pretty simplistic analysis, but I think it does show where there are those extreme pressure points in some of the regional areas.

That's if you can get a rental in the first place. There are two challenges: one, being able to pay for it, but two, actually being able to get one. In Kalgoorlie, the rental vacancy rate is around one per cent. In Bunbury, I think it's around half a per cent. Or in Karratha and Port Hedland, it's so low it's not even showing up on the group. And you might think Broome's a little bit of an outlier there, and it probably is on that one particular month. But you've got an incredibly seasonal rental market there. If these are May figures, by the time you looked at June and July, I think we would be back down to very minimal vacancy rates as well.

A balanced rental market is usually considered around three per cent. That's when you can get a rental with relative ease. Anything below three per cent is considered very challenging and what we're looking at in most areas is close to zero. You can't find a rental, you can't afford a rental if you can find one and it’s incredibly difficult to attract people to regional areas.

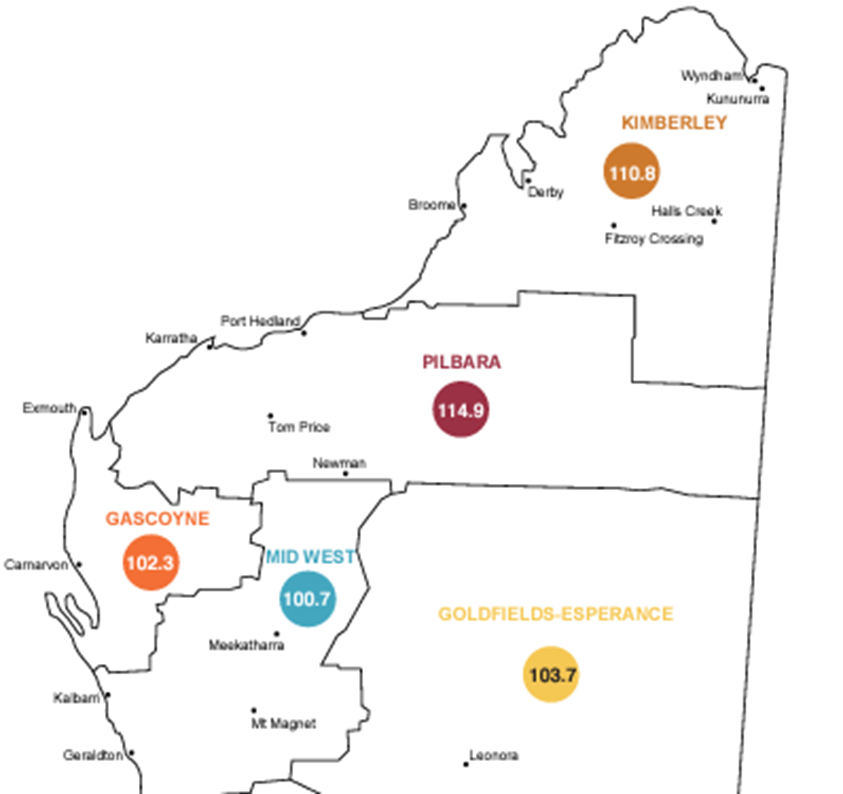

And rent is not the only thing that's more expensive in regional areas. This is the Regional Price Index that the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development puts out. This is the 2019 one, and it's probably even worse if we look now. Almost all regional areas are more expensive compared to Perth. 100 would be the same as Perth, so anything above 100 is saying it is much more expensive in regional areas than it is in Perth.

You've got challenges on the rental front, you've got challenges on the cost-of-living front, and you've got other sectors that are able to pay a lot more. It just really doesn't stack up for employees to work in low-wage sectors such as aged care in these regional areas.

Providers either have to offer higher wages, provide housing themselves, or even have fly-in-fly-out workforces, but how do you do that in an environment where a substantial number of providers are operating at a loss? It's an incredible challenge, and I do think we're likely to see more regional homes either consolidate or stop offering services due to these pressures, unless we see some sort of change or some more support there.

I want to talk now about the role of productivity and innovation. Productivity has been a pretty hot topic in the economy recently, and there is quite a lot of talk about how do we improve productivity in the care sector as one of our really growing sectors?

When we look at how substantial the workforce challenges are, it's clear that we need to do everything at our disposal and use all those levers to try and meet that demand. And productivity and innovation do need to be part of the solution, because it's one of the few things that you can do to actually decrease the demand for workers. If you're getting more out of your existing staff, you need fewer of them, so that can lead to some real improvements and soften some of those growing demand requirements.

People tend to go, "Oh my God, I don't want robots", when you start talking about technology and aged care, but it's really not about that. There are certainly really interesting things you can do with assistive technology. I'm sure there are people in the room that know a lot more about this than me, but it's things like that and reducing the burden of administrative work to allow for more face-to-face care and interaction.

When you look at surveys of why workers want to be in the sector as well, what they enjoy about their jobs – and actually job satisfaction is quite high generally in the sector -- it's because they want to do that face-to-face care, but they actually often don't have enough time in their day to do that because they're doing all the administrative work and other things.

If we can focus on technology that reduces that administrative burden, you get a double whammy of benefits there in terms of getting more out of your existing staff, but also making their work more enjoyable for them, which encourages people to stay in the industry.

There are other things that need to be done around improving the digital literacy of staff. It is a workforce that is not particularly digitally literate. That might be changing as we get more younger workers through, but there does need to be some work there if you're going to implement any technology changes.

But one thing that is really difficult around the productivity and innovation space in aged care is that we've got a situation where there's not much funding around. I don't think anyone's sitting around here thinking “I've got some spare cash, what can I spend it on?”

You probably don't have any spare time either, so you're dealing with day-to-day crises trying to get through what's going on today, a huge wave of regulatory changes that are coming, so how do you have time to take some time out, look to the future and think about how you can improve and innovate? And that's really difficult, particularly in a tight funding situation.

I do think there is a lot that can be done in the sector around improving productivity and getting more innovation and technology in, but I think until we can deal with some of the financial sustainability aspects and some of the basic workplace things in terms of boosting that workforce, there's not enough slack in the industry to be looking a bit more forward.

I'm going to finish by talking about a few of CEDA’s recommendations for increasing the workforce, and then I'll have a quick conclusion. But again, it's all around addressing as many levers as we can. Looking at the wages and the working conditions and particularly that progression through and the discrepancies with similar industries. It’s around getting more people into training and improving those training courses and making sure that's relatively cheap and easy to.

The dedicated migration paths are really important – we've been advocating for an essential skills worker visa that would bring in people on that personal-care worker level and allow them either a relatively long temporary visa or pathway to permanent residency. We do have the introduction of the labour agreements, but those are pretty challenging to get through, and we are still very strongly advocating for a new visa category.

There is that need for investment in new technology and also better knowledge sharing within the industry, which is what you're all doing today, so big tick there. There are a lot of providers that are doing really great things and coming together and sharing those and understanding what works is really important.

Just to conclude, workforce challenges are not improving, or certainly not improving at the rate and pace that we need them to, and we need continued efforts from the government and from industry in both the short term and the longer term to meet that need.

It is impacting on providers' ability to deliver appropriate care, and we have those particular issues in regional and remote areas, and there's more pressure to come. The upcoming increases in care minutes are a good thing in terms of improving the quality of care, but add more pressure on making sure we get that workforce.

And a whole other conversation, but really a strong part of this is that without sustainable funding, it's really hard to meet these workforce challenges. It does need to be part of the conversation: how do we properly fund the sector so that we can get the workforce that we need so that we can provide the quality of care that we need?