Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Looming structural adjustments including digital transformation, the energy transition and an ageing population will require an adaptive and agile labour market to deliver labour and skills where and when they are most needed.

In preparation for these transitions, Australia needs to reverse long-term trends of declining dynamism and job mobility, while addressing entrenched barriers in the labour market. To this end, the submission will comprise five individual papers on skills recognition, housing market barriers, occupational gender segregation, training for the long-term unemployed, and the structure of unemployment benefits.

Training to reduce disadvantage

CLICK HERE FOR PDF

Unemployment payments

CLICK HERE FOR PDF

Occupational gender segregation

DOWNLOADSummary

Australia is facing widespread skill shortages, with unemployment falling below four per cent in 2022 and job vacancies exceeding the pool of available workers. Future trends including digital transformation, an ageing population and the energy transition will exacerbate the demand for skilled labour. Known bottlenecks include:

- The public infrastructure pipeline announced by governments in recent years has been delayed due to a forecast shortage of more than 100,000 workers.

- Australia will need a sustained lift in labour to install around 33 gigawatts of new domestic generation in just over a decade to be on track for net zero by 2050. This is the equivalent of almost doubling current generation capacity in NSW.

- The government and the tech sector have a shared commitment of 1.2 million tech jobs by 2030, necessitating 650,000 new roles over the next 8 years.

- Defence spending and required workforce is also ramping up. The permanent Australian Defence Force and Defence civilian workforce will be up by 18,500 by 2040, and there is a strong commitment to local defence manufacturing in the $270 billion of spending forecast in the next decade.

Skills recognition

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

Australia’s skills mismatch

Australia has a range of mechanisms for developing and recognising skills, including certificates and degrees that are readily recognised by employers, as well as emerging modes of learning such as short courses and micro-credentials. Australia’s migration program is also strongly focused on skills.

Despite favourable settings for skill development and deployment, Australia has historically had above-average skills mismatch, predominantly workers who are over-skilled for their current job (See Figure 1). Contributing factors include large distances between major population centres, interstate differences in education and vocational training and weak housing supply responsiveness.1 For example, weak housing supply responsiveness contributes to expensive housing close to job opportunities, reducing the ability of people to move to a job that better matches their skills (see housing paper).

Figure 1

Skills mismatch is further increased by weak labour market integration of immigrants, who have over-education rates substantially higher than among Australian-born workers.2 Lack of local experience and networks is a key driver. Skills mismatch for migrants arriving between 2013 and 2018 is estimated to have cost $1.25 billion in foregone wages.3 CEDA will give further consideration to policy steps to improve the Australia’s migration system in a submission to the comprehensive migration system review announced at the Jobs and Skills Summit.

More generally, businesses, vocational and higher education providers need to work together on skills accreditation and advancing new ways of learning that develop work-relevant skills. This would entail some weakening of the demarcation between vocational education and universities, with scope for vocational students to benefit from pathways to advanced degrees and university students from more job-focused learning.

Better use of existing skills can also be driven by hiring decisions based on people’s skills rather than their educational credentials or industry-specific experience. Recognising skills enables businesses to hire the best person for the job – perhaps aided by some training in specific areas – rather than the most defensible candidate based on pedigree. International evidence indicates that degree holders in middle-skill positions have higher rates of voluntary turnover and lower levels of engagement, while commanding a material wage premium even though on average their performance is not materially better.4 A tight labour market can help push in the direction of prioritising skills over credentials: in the United States between 2017 and 2019 employers reduced degree requirements for 46 per cent of middle-skill positions and 31 per cent of high-skill positions.5

The remainder of this paper focuses on potential reforms to occupational licensing to improve the recognition of existing skills and relieve skill shortages.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Licensing prevents the best use of skills

Occupational licensing refers to specific legal requirements to practice an occupation, such as minimum qualifications or recent work experience. Occupations subject to licensing in Australia include healthcare, teaching, security services, trades such as plumbing, painting and electricians, and taxi driving.

Two reasons are commonly put forward for occupational licensing:

- To protect consumer and/or public safety; and

- To ensure a sufficient and reliable level of service quality.

There is a lack of recent data, but around one in five people employed in Australia worked in an occupation subject to registration requirements in 2011. This proportion varied from a low of 13 per cent in the ACT to a high of 21 per cent in Queensland.6 Internationally this is not unusual: regulated workers are estimated to account for between 15 and 35 per cent of the workforce across EU countries and in the United States.7,8 In some areas, occupational licensing coverage continues to increase. For example, the Victorian Government is in the process of introducing a new registration and licensing scheme for building tradespeople, beginning with carpentry then extending to over 20 different trades.9

Based on CEDA analysis using the OECD’s framework for administrative burdens, qualification requirements and mobility restrictions across 15 occupations, the stringency of occupational regulations in Queensland is consistent with restrictive regimes applying in Germany or Canada (See Figures 2 and 3). Occupational restrictions on professional services in Queensland are around average, but licensing for personal services such as taxi drivers, driving instructors, electricians and plumbers is relatively more restrictive. Queensland is presented here as an example because it is the only state not to have joined the national Automatic Mutual Recognition scheme (discussed below). Largely due to lower mobility restrictions under Automatic Mutual Recognition, occupational regulations in NSW are somewhat less stringent than in Queensland, but still relatively high for personal services. Compared with the United Kingdom, for example, licensing is much more restrictive in Queensland and NSW for building trades such as electricians, plumbers and painters.

Box 1

The OECD indicator of Occupational Entry Regulations

Von Rueden and Bambalaite present a composite indicator of the coverage and stringency of occupational entry restrictions across 18 OECD countries (not including Australia).10 The indicator distinguishes between occupational licensing, licensing only for supervisors and certification (where activities are not restricted but voluntary certification is needed to use a legally protected title such as ‘architect’). Regulatory barriers in 15 key occupations are assessed along three dimensions:

Administrative burdens: procedural hurdles set on obtaining authorisation to practice, including territorial restrictions and any registration requirements in professional associations;

Qualification requirements: the number of pathways to obtain the qualification, the duration of mandatory study and any mandatory practice or state exam requirements; and

Mobility restrictions: barriers to labour mobility between countries based on the presence and transparency of mutual recognition and obligation to take local exams before practising.

The benefits from licensing depend on its capacity to protect safety by ensuring the quality of goods or services supplied. However, most international research on this topic has failed to demonstrate quality improvements from stricter regulatory entry barriers, or a reduction in the quality of goods and services following an easing of such barriers.11,12,13 There are more likely to be benefits from licensing where consumers are particularly ill-informed about the quality of what they are purchasing, such as for specialised medical services. Public safety benefits can be more relevant where poor quality can create risks for members of the public who were not involved in the original dealings, such as a poorly constructed building. However, widespread occupational licensing in the building sector has not prevented problems from non-compliant cladding, water ingress leading to mould and structural compromise, structurally unsound roof construction and poorly constructed fire resisting elements.14

The costs of licensing come from higher barriers to entry to these occupations. As the Harper competition review noted, competitive impacts of licensing have not been adequately considered.15 Less competition leads to higher prices and lower employment in regulated professions.16,17 Occupational licensing can also restrict the ability of people to move to new jobs, where people licensed to work in one state are not automatically recognised to work in the same occupation elsewhere. In the US, regulations have been shown to stifle mobility between states,18,19 with one estimate suggesting interstate migration rates for workers in the most licensed occupations are almost 15 per cent lower than for those in the least licensed occupations.20

OECD analysis shows that reducing occupational restrictions in Germany to match those in Sweden could increase the contribution of labour reallocation to employment growth by 10 per cent and boost the productivity of the average firm by 1.6 per cent.21 The similar level of occupational restrictions in Queensland to Germany (and in NSW too for personal services) implies similar scope for gains in Australia, albeit there is variation in the stringency of restrictions across states. Applying this same productivity improvement to the roughly 15 per cent of Australia’s economy subject to occupational licensing, the nation could gain up to $5 billion each year from reform to match best-performing countries. Unlocking the full scale of benefits would involve removing mobility restrictions across all occupations and matching Sweden in terms of the overall stringency of licensing by removing licensing of taxi drivers, driving instructors and building trades (electricians, plumbers and painters). More modest reform could still yield billions of dollars in productivity benefits.

Licensing also has important distributional consequences: a large population of workers has fewer labour market opportunities, while a concentrated minority has an incentive to oppose reform to reduce licensing. Wages have been found to be as much as 10-15 per cent higher for those in licensed professions, after controlling for the characteristics of people who are licensed and unlicensed.22

Constraints on movement into regulated occupations mean that higher wages in these occupations come at the cost of lower wages in unlicensed professions. Licensing presents a particular barrier to suitable employment for migrants whose skills have been built internationally. This problem is exacerbated in occupations such as nurses and electricians, where migrants can satisfy skills assessment for Australia’s migration program but still fail to meet licensing requirements.23 Further, by relying primarily on historical pathways to build skills, notably apprenticeships designed around the needs of young male school leavers, licensing can also create barriers to new modes of learning that could build skills among other cohorts, such as older workers and women.24

There are better ways to protect consumers

Alternative approaches that do not involve the same occupational barriers to entry include shifting the focus of regulation from inputs to outputs, by setting quality standards for the goods and services provided, rather than setting standards for the professionals providing them. For example, under the Australian Consumer Law, a supplier must provide services with due care and skill, which are fit for purpose, within a reasonable time. And while hairdressers are subject to occupational licensing in New South Wales, elsewhere in Australia they do not need specific credentials but must comply with infection prevention and control requirements.

More effective regulation of building construction requires closer regulatory oversight, including on-site inspections of building works.25 Professional indemnity insurance is also important to support accountability for building work. Registration may continue to play a role, but should be done in a nationally consistent way that removes licensing of low-risk trades such as painting and decorating.

In the absence of occupational licensing, service providers can still signal the quality of their products through alternatives including warranties or guarantees, independent certification, development of a good reputation or membership of a professional organisation. New business models based on digital platforms that reduce transaction costs and information asymmetries have spread rapidly in recent years, making information about the quality of services more easily accessible, potentially reducing the need for regulating service provision.26

Recent changes do not fix the problem

The Automatic Mutual Recognition of Occupational Registrations scheme, which came into effect on 1 July 2021, has improved the recognition of occupational licensing across Australian states. The scheme removes the need for people to apply and pay for an additional registration or licence when working in another state or territory. Not all occupations are covered, however, and Queensland does not yet participate, which is of particular concern given the extent of licensing restrictions in that state and its role as the biggest net recipient of interstate migrants.

A further limitation of mutual recognition is that workers must still be licensed in one jurisdiction. It may even act as a barrier to more substantive licensing reform if that means workers from the reforming state can no longer work in other states.

Australia could enjoy greater long-term benefits from Automatic Mutual Recognition by assessing whether licensing is still required in occupations not subject to licensing in one or more jurisdictions.

Recommendations

1 OECD. (2017). OECD Economic Surveys: Australia. Paris.

2 CEDA. (2021). A good match: optimising Australia’s permanent skilled migration. Melbourne, from https://www.ceda.com.au/Admin/getmedia/150315bf-cceb-4536-862d-1a3054197cd7/CEDA-Migration-report-26-March-2021-final.pdf

3 Ibid.

4 Fuller, J., & Raman, M. (2017). Dismissed by Degrees How degree inflation is undermining U.S. competitiveness and hurting America’s middle class. Accenture, Grads of Life, Harvard Business School, from https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/dismissed-by-degrees.pdf

5 Fuller, J., Langer, C., & Sigelman, M. (2022). Skills-Based Hiring Is on the Rise. Harvard Business Review, from https://hbr.org/2022/02/skills-based-hiring-is-on-the-rise

6 Productivity Commission. (2015). Mutual Recognition Schemes. Research Report, Melbourne, from https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mutual-recognition-schemes/report

7 Kleiner, M. (2017). The influence of occupational licensing and regulation. IZA World of Labour. doi:doi: 10.15185/izawol.392

8 Koumenta, M., & Pagliero, M. (2017). Measuring Prevalence and Labour Markets Impacts of Occupational Regulation in the EU. Brussels: European Commission.

9 Victorian Government. (2022). Registration and licensing of building trades. Melbourne, from https://engage.vic.gov.au/registration-and-licensing-building-trades

10 von Rueden, C., & Bambalaite, I. (2020). Measuring Occupational Entry Regulations: A New OECD Approach. Paris: OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/296dae6b-en

11 Koumenta, M., Pagliero, M., & Rostam-Afschar, D. (2019). Effects of regulation on service quality: evidence from six European case studies. Brussels: European Commission, from https://op.europa.eu/ en/publication-detail/-/publication/bfd2b0e8-1943-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

12 Kleiner, M. (2017). The influence of occupational licensing and regulation. IZA World of Labour. doi: 10.15185/izawol.392

13 Powell, B., & Vorotnikov, E. (2015). Real estate continuing education: rent seeking or improvement in service quality? Eastern Economic Journal, 38(1), 57-73.

14 Shergold, P. and Weir, B. (2018). Building Confidence: Improving the effectiveness of compliance and enforcement systems for the building and construction industry across Australia, Report for the Building Ministers’ Forum.

15 Harper, I., Anderson, P., McCluskey, S., & O’Brien, M. (2015). Competition Policy Review. Commonwealth of Australia, from https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/Competition-policy-review-report_online.pdf

16 Koumenta, M., & Pagliero, M. (2017). Measuring Prevalence and Labour Markets Impacts of Occupational Regulation in the EU. Brussels: European Commission.

17 Kleiner, M. (2016). Battling over jobs: occupational licensing in health care. American Economic Review, 106(5), 165-70.

18 Hermansen, M. (2019). Occupational licensing and job mobility in the United States. Paris: OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1585. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/4cc19056-en

19 Ghani, A. (2019). The Impact of the Nurse Licensing Compact on Interstate Job Mobility in the United States. OECD Economic Survey of the United States: Key Research Findings. Paris: OECD Publishing.

20 The White House. (2015). Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers. Washington.

21 Bambailate, I., Nicoletti, G., & von Rueden, C. (2020). Occupational entry regulations and their effects on productivity in services: firm-level evidence. Paris: OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1605. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c8b88d8b-en

22 Kleiner, M., & Krueger, A. (2010). The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 48(4), 676-87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2010.00807.x

23 Productivity Commission. (2022). 5-year productivity inquiry: A more productive labour market, from https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/current/productivity/interim6-labour

24 NSW Productivity Commission. (2021). Productivity Commission White Paper 2021. OECD. (2017). OECD Economic Surveys: Australia. Paris.

25 Shergold, P. and Weir, B. (2018). Building Confidence: Improving the effectiveness of compliance and enforcement systems for the building and construction industry across Australia, Report for the Building Ministers’ Forum.

26 Farranto, C., Fradkin, A., Larsen, B., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2020). Consumer protection in an online world: An analysis of occupational licensing. NBER Working Paper Series. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w26601

Summary

Housing plays a critical role in our lives, providing shelter, a meeting place for family and friends, a place to keep our belongings and, increasingly a place to work. Housing is also an enabler of geographic labour mobility: in most cases, people only move for work if they can live within commuting distance. While individuals must weigh up the costs of any move – including the implications for the jobs and education of other household members – a well-functioning housing market should not create additional barriers. Australians devote a relatively high share of spending to housing, heightening its importance when choosing where to work.

Housing affordability and labour mobility

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

Housing can be a barrier to moving for work

Compared with European countries and the US, Australians regularly move house, but less than one in 20 of these moves are for employment (Figure 1). Private renters, who comprise around one third of households, are most likely to move. Even after accounting for differences in characteristics between renters and owners, private renters still exhibit the highest rates of geographic mobility.1 Lack of security of tenure is a factor: more renters are forced to move by their landlord than choose to move for work or study.2 In the US, by contrast, renters are more than 10 times more likely to move for a new job than due to eviction.3

Australians devote a relatively high share of spending to housing (Figure 2). Poor housing affordability is an important barrier to moving to a better-suited job, as median house prices now exceed $1.25 million in Sydney and $930,000 in Melbourne.4 Low interest rates and changed working patterns during the pandemic saw house prices soar. Evidence from the US suggests the shift to working from home during the pandemic could explain as much as a 15 per cent increase in house prices and rents due to increased demand for housing space.5 While prices have begun to fall with rising interest rates, dwelling prices in October 2022 were still more than 20 per cent higher than before the pandemic when averaged across capital cities, and more than 40 per cent higher in Brisbane and Adelaide.6 The average deposit required by a first home buyer is now more than two and a half times what it was two decades earlier, far outstripping earnings growth.7 Meanwhile, the challenge of getting to work intensified as commuting times increased to 4.5 hours per week on average in 2017, up from 3.7 hours in 2002.8 High house prices can also indirectly reduce job mobility through risk aversion due to indebtedness.9 Australia ranks fifth in the OECD for the scale of gross household debt relative to GDP.10

Partly as a consequence of low job mobility, the match between skills and jobs in Australia is relatively poor, with more than 40 per cent of workers either under- or over-qualified for their job (see skills recognition paper). Increasing the responsiveness of housing supply can reduce the level of skills mismatch in the labour market, boosting Australia’s productivity by as much as 2 per cent,11,12 or around $50 billion in additional production per year.i Reducing development approval timeframes and housing transaction costs such as stamp duty could boost productivity by around a further one per cent each.ii

.png)

Increase supply and reduce transaction costs

Reforms are critical to increase the capacity of housing supply to respond to higher demand, particularly as immigration recovers and if greater working from home continues to increase demand for housing and contribute to smaller households. For example, the NSW Government has estimated that 42,000 new homes will need to be built each year in the state,13 requiring a record level of new builds to be sustained every year for 40 years.

Growth-accommodating reforms to planning arrangements are crucial and have a statistically significant positive effect on housing supply.14 For example, upzoning and relaxed land-use regulations in Auckland in 2016 added around four per cent to the city’s housing stock in subsequent years and saw rents grow considerably slower than in the rest of New Zealand.15 By allowing higher density development in inner areas and transport corridors, such development can also boost productivity through shorter commutes.16 Improved clarity and defined timelines for development approvals are also important to reduce risk for developers, enabling them to ramp up production when economic conditions are favourable.17

Planning practices that constrain development of medium-density housing are widespread, such as bans on townhouses in low-density residential suburbs that make up large parts of Brisbane and Sydney. The institutional arrangements under which planning operates – with highly decentralised decision-making and involvement of multiple levels of government – are the most likely to lead to restrictive land-use planning among OECD countries.18 Restricting development has important distributional consequences, contributing to higher house prices that benefit wealthy owners of multiple properties at the expense of first home buyers. Strict land use regulation can thus drive greater segregation between wealthy and middle-income households.19

Planning and zoning restrictions should be relaxed to allow higher density development in appropriate locations. Land-use rules are necessary to prevent inappropriate development and protect community values, but restricting development means more housing is needed elsewhere, often further from city centres where infrastructure is not as well-developed, exacerbating congestion. An example of reform to enable density and overcome local neighbourhood resistance by taking a broader perspective is the Low Rise Housing Diversity Code in NSW, which fast tracks development approval for dual occupancies, multiple-family manor houses and terraces. More generally, a forward-looking approach is necessary, prioritising relaxed regulation and supporting infrastructure in regions likely to see significant jobs growth under key shifts such as the energy transition.

Key reforms to planning and zoning vary by jurisdiction, requiring analysis to proceed at the local government level, but as set out by the Productivity Commission a good starting point would involve:20

The housing accord announced in the October 2022 Federal Budget is a positive starting point for increasing supply through direct support for affordable housing and laying the foundations for institutional ownership (including by superannuation companies). Critical to its success in practice will be the outcomes from the state and territory government commitment to work with local governments to deliver planning and land-use reforms. Also important is integrated regional planning that brings together housing and infrastructure needed to service a greater population and future workforce needs. There are examples of positive steps in this direction in NSW through the Greater Cities Commission and Regional NSW.

Stamp duties on the purchase of houses are a direct barrier to moving for work; federal, state and territory governments should cooperate to overcome the short-term fiscal costs of replacing stamp duties with more efficient taxes. The importance of stamp duties for state and territory revenue has grown over time as house prices have soared (Figures 3 and 4). Stamp-duty revenue has tripled in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania over the past decade and is at record highs in all states.

Stamp duty is a volatile source of revenue that is difficult to forecast and subject to property market downturns. As it reduces housing investment and mobility, stamp duty is a particularly inefficient tax. In NSW alone, replacing stamp duty with land taxes is expected to boost long-term incomes by $10 billion.21 Politically, however, this has proven difficult: the ACT Government took the welcome decision to phase out stamp duty over 20 years from 2012, but in 2021-22 stamp duty revenue was still 80 per cent higher than a decade earlier.

From 2023, NSW will allow first-home buyers to choose to pay an annual property tax instead of stamp duty, but such a piecemeal approach will not deliver the full benefits of a complete transition from stamp duties. It also has the potential to push up house prices disproportionately in the lower end of the market by increasing the deposits that first home buyers can make.22 The almost $3 billion spent in 2020 on first home buyer grants and stamp duty concessions also pushes up house prices by boosting demand; this money would be better spent on measures to reduce homelessness.23

Make renting a more viable long-term option

While many Australians still seek to own their own home, for others, renting can be a more attractive option. For example, young and/or mobile households may not wish to buy and sell a house with each move. As the Productivity Commission has noted, homeownership is not an end-goal and does not improve society on its own.24 But for rental housing to provide for the needs of a diverse set of renters, they need security of tenure. Benefits of secure tenure include improved connections to community, better health outcomes and higher levels of social and economic participation.25 Indeed, stable and secure rental tenure is protective of mental health, with average mental health of private renters lower than that of comparable homeowners until five-to-six years of tenure, when the difference becomes indistinguishable.26

Greater rental security should be pursued by properly removing landlords’ capacity to evict tenants without cause.iii While some jurisdictions have made reforms in this direction in recent years, it is still possible to evict tenants without grounds at the end of a fixed-term tenancy (with 30 days or less of notice in NSW, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory) or by demanding a disproportionate rent increase. Although tenants can dispute a rent increase if they think it is excessive, in practice this is complicated as it requires comparison of rents with similar properties.

Regulations that control rental prices across-the-board carry significant economic costs, but there can be benefits from simple metrics to regulate price increases for existing tenants. By pushing returns below market rates, rent control holds back the supply of new housing27 and works against mobility by locking people into favourable arrangements.28 Equally, however, once tenants are already living in a property, they can be in a situation of “economic hold up” and vulnerable to excessive rent increases where they do not want to move away from work, school, family or friends. A solution would be only to allow rents on existing tenants to be increased in line with a local measure of rental prices (with allowance made to recoup expenditure on major renovations). Such an approach in Germany has maintained a link with market rents without forming a barrier to investment.29

Enable institutional investment in rental housing

Building a stronger market for institutional investors in rental housing could also help, by reducing eviction due to the landlord’s personal situation, for example if they or a family member wish to move in. One way to do this is via ‘build to rent’ whereby the developer maintains ownership of dwellings and rents them out after completion. Institutional investors currently play a small role in the Australian market, with the largest investors only holding a few thousand units. In Germany and the US, by contrast, the largest institutional investors hold a combined total of more than half a million dwellings.30

Institutional investors face tax disadvantages relative to individual landlords in Australia due to land tax, which is levied in a progressive fashion on the total value of non-own-home land holdings and thus favours holders of few properties. They are also disadvantaged because they do not have access to negative gearing, whereby annual losses can be offset against unrelated wage income. These disadvantages are particularly strong for houses, where they are magnified by high land values and low rental yields (Figure 5).iv

There is currently an opportunity for institutional investors as yields rise and land values fall, particularly build-to-rent investors who benefit from land-tax discounts in NSW, Victoria and Western Australia. This opportunity could be enhanced by flattening the payment schedule for land tax and reforms to reduce the importance of negative gearing. The US, for example, has a vibrant build-to-rent market and only allows individuals to make tax-loss write-offs against other forms of passive income (i.e. not against wage income). Student housing demonstrates the potential for institutional investment in Australia where there is a more level playing field: the largest owners have more than 60,000 beds under management in a market where average yields exceeding 6 per cent (prior to the pandemic) make negative gearing less relevant.v

More support for low-income renters

Rent increases greater than wage growth during the recovery from the COVID pandemic point to the need to strengthen support for low-income renters to protect them from a cost-of-living crunch. Asking rents increased by more than 10 per cent in the year to September 2022,32 which easily exceeds average wage growth of around three per cent and will gradually flow through to more private renters as fixed contracts expire. Low-income private renters face the greatest housing affordability challenges of all tenure types, with 20 per cent of renters in the lowest income quintile spending more than half of their gross wages on rent.33

Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) is a valuable way to support renters without dampening mobility, as it is fully transferable. It also has very little negative impact on employment.34 CRA should be ramped up for those in greatest need, at least in line with recent rent increases, while maintaining or improving targeting to manage budgetary costs.35 For example, reforming CRA eligibility rules to better reflect housing need would substantially improve housing affordability while generating cost savings. Improving targeting would also minimise the extent to which higher payments would raise rents through increased demand.

Expand social housing to improve affordability and employment

Social housing can play a vital role as a safety net for those who are not well-served by private rental markets. There has been little change in the number of social housing properties since the Social Housing Initiative ended in 2012. The proportion of the population who live in such housing declined from about 4.8 per cent in 2012 to 4.2 per cent in 2021,36 substantially below the 7.0 per cent average for OECD countries.37

Since social housing has a strong protective effect against homelessness,38 the failure of supply to keep up with population growth is a contributing factor to the increase in homelessness between the 2011 and 2016 censuses and the 18 per cent increase in people seeking support from specialist homelessness services between 2011-12 and 2020-21.39 There are some initiatives to increase supply, most notably in Victoria, where the government in 2020 announced a $5.3 billion package to build 12,000 new social housing, affordable and low-cost homes. New stock must address the need for smaller units: most social housing households are single adults, but only 26 per cent of the stock is one-bedroom or a bedsit, as it was built to meet different needs historically.40

Overcoming the barriers to unlocking institutional investment in affordable and social housing can contribute to supply. Collaboration and partnership across the public, community, and private sectors, underpinned by firm funding commitments and viable delivery mechanisms, has the potential to improve the residential housing stock while supporting skills and capacity building across the housing industry. Case studies in Australia and internationally demonstrate that there is private sector appetite and capacity to deliver affordable and social housing, and that there can be positive outcomes where incentives are aligned between partners.41

The labour market effects of improving social-housing provision are likely to be small. Nonetheless, it should be delivered in a way that allows residential mobility and does not disincentivise employment. More than half of social-housing households receive the age or disability-support pensions, and the Department of Communities and Justice NSW has found that about 57 per cent of adults in public housing were unlikely to ever be able to work.42 For those who can work, however, stable tenure means social housing can act as a springboard to improve workforce participation.43 Important here is avoiding lock-in effects, where tying support to a specific housing unit or rapid withdrawal of support as income increases can act as a disincentive to moving to (better) work.

As the Productivity Commission has recommended, portable rent assistance should be trialled for social-housing tenants.44 Tailoring the magnitude of rent assistance (relative to market rents) to the household instead of the property they are allocated would result in better targeting to disadvantage. It would also sharpen incentives to better match households to the stock of rentals, since the household would need to pay the difference in market rent for a larger property. Better integrating housing assistance with income-support arrangements could prevent excessive disincentives to work and allow for tenant mobility, including moves for jobs for those able to work. Portable rent assistance would entail extending CRA to public-housing tenants. This would be a significant additional federal expenditure, but would reduce complexity and address the current lack of coordination between state-based public housing and CRA.45

Recommendations

Summary

Australia’s current strong labour market has helped bring the unemployment rate down to near 50-year lows. Lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic and strong fiscal support saw saving rates soar, while low interest rates and the rebound in consumer spending underpinned robust economic growth as the economy reopened. In conjunction with strong federal and state infrastructure spending, digital transformation and the energy transition, this has led to widespread labour shortages. At a national level, unemployment brings significant economic and social costs through limiting productive potential, increasing reliance on government welfare and reducing the social engagement of those out of work. At a personal level, unemployed people experience lower incomes, poorer mental health and lower life satisfaction.[i],[ii],[iii] The historically low unemployment rate has thus delivered substantial benefits for those newly able to find work.

Training to reduce disadvantage

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

The strong labour market has helped to reduce the number of long-term unemployed Australians – those who have been unemployed for more than a year. But this decline has been more gradual than for those who have been unemployed for a shorter period (Figure 1). The proportion of Australians who are long-term unemployed is around the average of similar developed countries (Figure 2). There are still 70 per cent more long-term unemployed people in Australia than before the global financial crisis in 2008, with more than twice as many youth (aged 15-24) and older people (aged 55-64) unemployed for two years or more.[iv] Prior to the pandemic, Indigenous Australians were 3.8 times more likely to be unemployed than non-Indigenous Australians, with more than one third unemployed for 12 months or more.[v] The strong labour market offers an opportunity to significantly reduce the number of people in long-term unemployment, with concentrated benefits for youth, older and Indigenous Australians. People who are unemployed for longer are less likely to find a job and can suffer long-term earnings penalties even after they find work.[vi],[vii]

Australia spends relatively little on getting people back into work.

One way that governments can help get people back into work is through ‘active labour market’ policies, which seek to give more people access to good jobs via job-search assistance, wage subsidies, public-sector jobs programs or training. Australia spends relatively little on such assistance, even in terms of spending per unemployed person (Figure 3).[1] Employment assistance spending has been on a declining trend since 2004.[viii] Spending on wage subsidies to get people back into work is particularly low: $147 million in expected expenditure in 2022-23[ix], or less than 0.01 per cent of GDP. These are predominantly one-off payments (of up to $10,000) to businesses for hiring eligible individuals rather than ongoing payments that can help with longer-term skill development and poverty reduction through work.

[1] Countries that spend a lot on active labour market programs are typically those with higher taxation as a share of GDP, particularly northern European countries. However, there are also examples of countries with similar or lower tax-to-GDP ratios but higher active labour market spending per unemployed person, such as Korea, Ireland and Switzerland.

While the effectiveness of individual measures varies (discussed below), spending to get people back into work is associated with positive macroeconomic outcomes. Across a sample of 25 OECD countries, higher spending on active labour market policies per unemployed person is associated with significantly higher employment and productivity (though this relationship does not imply causation).[x] A country’s overall spending on active labour market policies is also a key factor in predicting earnings losses from job displacement[xi] (an indicator on which Australia performs poorly[xii]). From a government-spending perspective, the social return on employment services can be threefold, through reduced spending on benefits and services and increased tax revenue.[xiii]

In addition to low levels of spending on active labour market programs, Australia is also unusual in outsourcing a large proportion of its job-services system to non-government providers. Most OECD countries deliver job services through their public employment service. Outsourcing and focusing on outcomes rather than inputs provides a number of benefits through greater efficiency, incentives to minimise costs while maintaining quality as assessed via ‘star ratings’ and encouraging private-sector innovation in service delivery.[xiv] Effectiveness in helping job seekers gain work has improved over time, with an average cost-per-employment outcome of around $2500 in recent years.[xv][xvi] Hundreds of thousands of people find jobs through the system each year. However, some aspects have not worked well:

- Incentives have not been strong enough for those who are relatively hard to place in work, with around one in five job seekers remaining in the system for more than five years.[xvii] This contributes to the low cost-per-employment outcome mentioned above, as effort is directed towards job seekers who are relatively easier to place;

- Caseloads for job-service consultants are high, with 148 job seekers per consultant;[xviii]

- Payments do not reward long-term outcomes, as they end once a participant has remained in employment for 26 weeks;

- Job service providers can claim payments for referring jobseekers into courses run by the same company or a related entity, a conflict of interest that has supported unhelpful courses;[xix]

- Job service providers have a role enforcing obligations for job seekers. Historically this has involved error rates of up to 50 per cent[xx] and it can undermine the service provider/client relationship[xxi]; and

- Public access to employment services data is limited. It is released irregularly and selectively.[xxii]

Help for jobseekers should focus on building skills

Developing human capital is the key to improving long-term outcomes for jobseekers. The rich international literature on what works in getting people back into work shows that job-search assistance and public-sector job-creation programs do not provide significant long-term benefits for employment.[xxiii] Job-search assistance can help people find jobs in the short term, but it displaces other job seekers rather than creating additional jobs (particularly in weak labour markets[xxiv]) and fails to achieve long-term employment benefits. Public-sector jobs programs often fail to develop skills that are needed in the labour market. And participation in Australia’s ‘Work for the Dole’ scheme has been found to significantly reduce the likelihood of coming off unemployment payments, as it causes participants to spend less time looking for a job.[xxv]

Programs aimed at building human capital include work-relevant training and wage subsidies for private-sector employment. The positive effects of these programs have been found to accumulate over time, with the greatest benefits accruing in the long run.[xxvi] Programs targeting long-term unemployment have the largest benefits.[xxvii] Training is particularly important given the big structural transitions that the Australian economy is facing: Australians may need to undertake a third more education and training by 2040 to adapt to the future of work.[xxviii] Strong foundational skills in literacy and numeracy are critical to enable lifelong learning, which can be a barrier for older workers as on average these skills are lower for Australians aged over 45.[xxix]

Workforce Australia offers a number of benefits

The Federal Government replaced its Jobactive employment service with Workforce Australia in July 2022. The new model responds to a number of problems with Jobactive as recognised by the Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel. Key changes include:

- An emphasis on digital service delivery (via Workforce Australia Online) for jobseekers who are job-ready and digitally literate, increasing efficiency of services for those with fewer barriers to work. This can free job-service consultants to provide intensive case management to those who need it most;

- Enhanced services to support better targeted and tailored programs for disadvantaged job seekers;

- Broadening of mutual obligations for jobseekers based on a points system for engaging in activities including training. The previous test focused on the number of job applications submitted. Jobseekers must accumulate 100 points per month to meet mutual obligations, which can include up to 20 points per week for education and training, migrant English training, employment programs or employability skills training.

The Government should also make enforcement squarely a responsibility of government rather than employment-service providers. Providers would still need to share information with government, but making government responsible for enforcement of mutual obligations would enable a more cooperative and productive relationship between job-service providers and jobseekers. As ACOSS has recognised, placing too much emphasis on compliance and enforcement “…means that interviews with employment services are mainly about compliance rather than job referrals, training, wage subsidies, or other things that would actually help people land a job”.[xxx] Mutual obligation is an important part of the Australian welfare system, but people can only get a job when they have the appropriate skills for the jobs that are available. Shifting the responsibility of service providers from enforcement to service provision would help develop those skills.

Well-targeted subsidies can deliver economic and equity benefits.

The tight Australian labour market offers a wealth of opportunities for jobseekers. However, the employment-services model has not delivered good outcomes for workers affected by structural adjustments whereby some industries and firms grow while others shrink. For example, after automotive manufacturing closures, roughly one-third of workers maintained their careers, one-third dropped back to less skilled jobs and one-third did not return to the labour force, with these outcomes little changed between the Mitsubishi Lonsdale plant closure in 2005 and the closure of remaining passenger vehicle manufacturing in 2017.[xxxi] More broadly, more than 100,000 Australians remain in long-term unemployment, split fairly evenly between men and women. While older people are more likely to be unemployed for two years or more, more than half of people in long-term unemployment are aged under 45,[xxxii] which increases the potential lifetime benefits of connecting these people with the labour market. There is an urgent need to do better given the prevalence of skill shortages and looming structural adjustments associated with digital transformation, the energy transition and an ageing population.

One approach that has worked internationally is sectoral employment programs, which train job seekers in industries and occupations expected to have strong local labour demand and opportunities for long-term career advancement. Targeted sectors have typically included healthcare, information technology and manufacturing. Key features of effective sectoral employment training programs in the United States have included:[xxxiii]

- Upfront screening of applicants for basic skills and motivation;

- Occupational skills training targeted to high-wage sectors and leading to an industry-recognised certificate;

- Career-readiness training (sometimes referred to as soft skills);

- Wraparound support services for participants such as career coaching and case management; and

- Strong connections to employers.

Sectoral programs have been found to generate substantial and ongoing earnings gains of 11 to 40 per cent, with long-term benefits driven by access to higher-wage and higher-quality jobs.[xxxiv] Transferable and certified skills are a key element in the durability of earnings benefits and in helping minority workers gain opportunities in high-wage sectors.[xxxv] Such training can be underprovided in the private market where it is transferable, as part of the gain will accrue to future employers. The focus on sectors with current and projected strong labour demand and close interaction with employers helps to reduce labour market misalignment that can hinder some publicly sponsored training programs.[xxxvi] Focusing efforts on positions in high demand in rapidly expanding parts of the labour market can also help avoid displacing other jobseekers.

Successful Australian programs that could be built upon or scaled up include effective projects under the federal ‘Try Test and Learn’ Fund, which provided funding for 52 projects seeking to reduce long-term welfare dependence by supporting at-risk groups. An evaluation concluded that while evidence is still incomplete, some projects showed early signs of having positive effects on workforce participation and there was suggestive evidence in support of an employer demand-led approach.[xxxvii] Another example is Jigsaw, a social enterprise that seeks to transition people with disabilities into regular employment. Participants receive training and IT work experience (in documentation data management) before being placed in award-wage employment. This aligns with lessons from US sectoral employment programs, where providers found that a two-step path with training then work placement had better results than immediate placement.[xxxviii] Along similar lines, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) has recommended making the youth PaTH training program more vocational and linked to work experience.[xxxix]

Key to learning from successful (and not so successful) programs is setting up rigorous independent evaluation from the outset. Program design needs to include variation across locations and/or time that can be used in conjunction with administrative data to test for causal effects. Data should be publicly available and independent experts should be involved in designing and implementing the evaluation strategy. Generating new insights into what works was a key objective of the Try Test and Learn Fund, but in practice evaluation has been incomplete. Evaluation can help programs target populations for whom the benefits are greatest, for example women, youth, Indigenous or remote communities. When assessing social returns on investments that reduce future welfare spending it is important to develop data and evidence to capture long-term fiscal savings, as in New Zealand’s Investment Approach, which can quantify the large potential benefits from breaking cycles of disadvantage.[xl]

Wage subsidies can also achieve good outcomes. An example is the Tasmanian Jobs Programme pilot, which had positive sustained employment outcomes for participants, although take-up was low due to low program awareness and relatively small incentive payments.[xli] Medium and long-term unemployed people appear to benefit the most from wage-subsidy programs.[xlii] Wage subsidies are particularly pertinent given the high effective tax rates faced by people receiving jobseeker benefits, with people losing 50 per cent or more of any increases in their income as benefits are phased out.[xliii] Returning some of this taxation through wage subsidies can play a valuable poverty reduction role through increasing employment where wages are fixed (for example at Award rates) or increasing low take-home wages where employers pass some of the wage subsidy on via higher wages. The downside of wage subsidies is that they can carry large deadweight costs from subsidising jobs that would have existed anyway, which can be reduced through tight targeting of eligible jobseekers and monitoring employer behaviour.[xliv]

Recommendations

CEDA makes three recommendations to help the long-term unemployed find suitable, long-term work:

- Build on the shift to Workforce Australia by:

- Scaling up training for hard-to-place job seekers via employment programs targeted at local unemployed and employers, with a greater focus on long-term outcomes. This would entail:

- An industry-driven approach, with close involvement of employers and a focus on higher-wage industries and occupations;

- Screening applicants for basic skills and motivation;

- Occupational skills and career-readiness training; and

- Work placement supported by career coaching and case management.

- Extending the duration and generosity of wage subsidies for employment of medium- and long-term unemployed people; and

- Monitoring and evaluating new spending so that successful programs can be scaled up and less successful programs ended. Independent evaluation should be a part of program design, including through testing different programs over time and in various locations. This should be supported by regular release of employment-services caseload data, similar to that released for income-support recipients.

- Scaling up training for hard-to-place job seekers via employment programs targeted at local unemployed and employers, with a greater focus on long-term outcomes. This would entail:

- Remove the requirement for service providers to enforce activity requirements. They should focus instead on training and placement.

- Ban employment-service providers from referring job seekers to their own training programs, removing the potential for conflicts of interest.

.png)

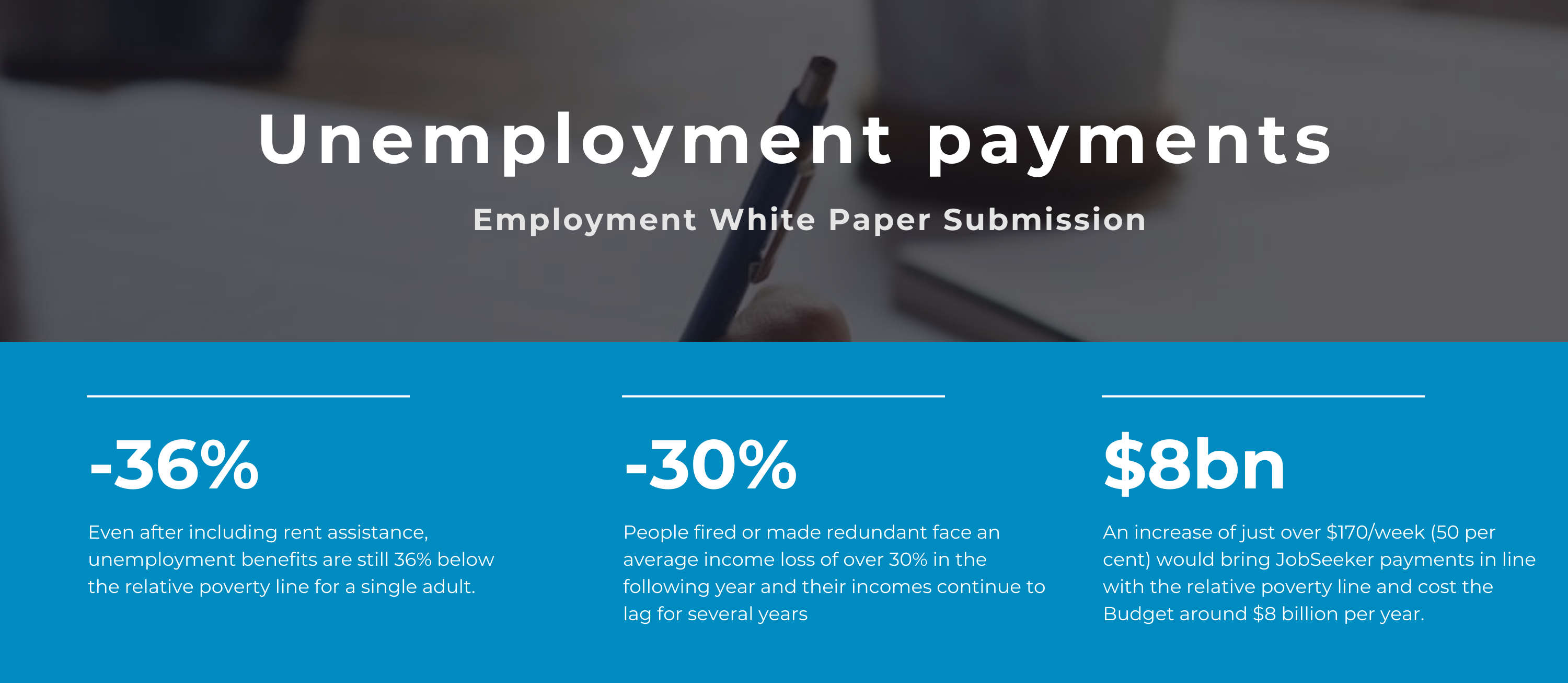

Summary

- The absence of public unemployment insurance and low payment rates under JobSeeker mean that most Australians who lose a job face large income losses in the year after being made redundant, compared with other countries.

- Australian unemployment benefits as a share of the average wage rank second lowest among 35 OECD countries for someone who has lost a job in the past two months.

- Large income losses can contribute to Australia’s low job mobility and poor skills matching.

- Combined with risk aversion, this can mean people are unwilling to move to a higher skilled but less secure job.

- Those who lose a job can face a financial imperative to take the first job, rather than the best job.

- The cost, complexity and potential unintended consequences of unemployment insurance evident in other countries weaken the case for its introduction in Australia at present. Rather, policymakers should prioritise reforms that increase job mobility within the existing social welfare structure through:

- A higher rate of payment for JobSeeker benefits; and

- Making long-service leave portable across employers.

Unemployment payments

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

Unemployment benefits are low by international standards

Unemployment benefits as a share of the average wage are thus very low in Australia for someone who has lost a job in the past two months, ranking second lowest among 35 OECD countries. The rate of unemployment benefits in Australia is also below the OECD average for the long-term unemployed.

Dynamic markets can lead to job displacement

Looming structural adjustments including digital transformation, the energy transition and an ageing population will require an adaptive and agile labour market to deliver labour and skills where and when they are most needed. In the near term, rising interest rates and tighter funding conditions for start-ups mean that redundancies are set to increase.

.png)

Summary

- Occupational gender segregation is the unequal distribution of male and female workers across and within job types.

- High occupational segregation persists in Australia, despite increasing female workforce participation.

- The skilled migration system also contributes to occupational segregation as female migrants are more likely to be secondary applicants to their partner’s visa, and to work in lower-paid occupations.

- High gender segregation limits job mobility, stifling labour-market flexibility and productivity. It is a complex issue, driven by many economic, social and historical factors.

- Reducing the ‘motherhood penalty’ and changing workplace cultures that limit flexible work will increase equality of opportunity, helping to reduce segregation.

- Tackling gender segregation directly within occupations requires addressing disparities in STEM education, the number of women in leadership and gender stereotyping.

- Employers have a major role to play, including through blind hiring and flexible-work practices.

Occupational gender segregation

.png)

Sebastian Tofts-Len

Graduate Economist, CEDA

.png)

Andrew Barker

Senior Economist, CEDA

Occupational segregation has declined gradually since the 1960s, and continues to do so, although the differences remain large. In particular, there is still a low proportion of women in traditionally male-dominated industries such as construction, mining, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and manufacturing. Conversely there is a low share of men in female-dominated industries such as health and education.

CEDA's Submission to the Employment White Paper

Occupational gender segregation

Some common occupations have become even more segregated over time. In 1986-87, 37 per cent of hours worked by women were in female-dominated jobs. In 2021-22 it was almost 44 per cent. In the same period the share of hours worked by females in male-dominated jobs declined from 16.6 per cent to 11.2 per cent. And even in female-dominated industries, men still disproportionately hold more of the leadership positions.

Average income is generally higher in male-dominated jobs

*This doesn't take into account hourly rate and only shows total income for the year 2019-2020.