Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

This collaborative paper has been produced with contributions from experts, stakeholders and CEDA members. CEDA’s objective in publishing this paper is to encourage constructive debate and discussion on a matter of national economic importance.

Justice is a critical institution underpinning economic and social development. Providing access to world-class justice and rehabilitation can help both the victims and perpetrators of crime, while minimising its associated economic and fiscal costs.

This paper provides a foundational framework outlining the clear need to reform the imprisonment of women in Australia. It seeks to highlight the key issues and emphasise the urgent need to reduce rates of female imprisonment through a nationally consistent approach. This will help to improve workforce participation and life outcomes, while also reducing wasteful government spending at a time of urgent budget repair. This report does not seek to detail all the complexities of the issue of the incarceration of women.

Across all of its work, CEDA’s purpose is to shape economic and social development for the greater good.

Incarceration rates, spending on prisons and recidivism are all rising, even as rates of serious crime are not. At the same time, there is clear and strong evidence on the benefits of alternatives to incarceration that require less spending and achieve better outcomes.

Government spending on approaches to criminal justice that are destroying critical human capital is rising. With tight labour markets, the need for budget repair and growing demands on government resources, we must challenge ineffective policies and programs wherever they exists.

This report focuses on Australia’s increasing rates of female incarceration, which are particularly costly from an individual and societal perspective.

Our aim in releasing this report is to bring together a broader range of voices to generate momentum for change, with immediate focus on:

- Reducing the number of women on remand;

- Providing better support to women released on bail; and

- Diverting women to community-based sentences and programs as an alternative to imprisonment.

CEDA will advocate on this issue with governments and other stakeholders, and actively promote evidence on alternatives to female incarceration to drive better individual, community and economy-wide outcomes.

The outcomes we are seeking include:

- Reduced government spending on corrective services;

- Reduced incidence of intergenerational disadvantage;

- Improved rates of female, particularly among vulnerable and disadvantaged women; and

- Better individual and family health and wellbeing.

Over time, lessons learned from reducing female incarceration should inform broader justice reform. That spending can and should be better invested in justice reform and on other areas of need.

This is an area in which government, business and community all have an interest in pursuing better outcomes. We would like CEDA members and others to consider how they can add their voices to calls for reform.

Public debate about reforming Australia’s criminal justice system is complex and challenging, and for many very personal. CEDA’s 2018 Community Pulse survey showed Australians want to be safe. They place importance on reducing violence in homes and communities in terms of their personal priorities, and see tough criminal laws and sentences as a very important issue for the nation.

This focus on preventing serious crime is understandable, but it is impossible to prevent or eliminate all crime. While the justice system should do all that it can to keep society safe from violence and harm, it must also seek to rehabilitate in order to prevent reoffending, and rely on incarceration only where the risks to society justify the costs of imprisonment.

Tough-on-crime policies such as rigid approaches to bail come with considerable economic and social costs. One unintended consequence is that too many people – in particular, a growing number of women – are becoming trapped in a system that is perpetuating the disadvantage that brought them into the system in the first place. This cycle captures not only the individuals themselves but also their children and families, contributing to an intergenerational cycle of disadvantage. It places a significant burden on the individuals caught in the system and costs taxpayers a rapidly increasing amount – spending plus depreciation in the sector was $5.43 billion in 2020-21, up 5.1 per cent on the year before.

There is growing recognition that current approaches are not working. As crime rates fall, incarceration rates are increasing, most markedly for women, and in particular Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Many of these women are themselves victims of violence, already facing significant physical and mental health challenges. Perhaps most startling, many receive relatively short sentences, or are unsentenced. As one example, more than 50 per cent of women in custody in Victorian prisons are unsentenced.

All of this is coming at a rapidly growing cost to taxpayer – in fact criminal justice is one of the fastest growing areas of government expenditure. Against the backdrop of significantly weaker fiscal positions after the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing investment needs in so many other areas – energy transition, climate adaptation, disability and aged care to name a few – we can no longer afford to ignore policies that are becoming increasingly expensive and ineffective. We must expect more from our criminal justice system.

These are complex and politically charged issues. But CEDA members across the non-profit, academic and business sectors, alongside other stakeholders such as community services, have challenged us as an independent think tank to address these issues. To start a different conversation and motivate change, CEDA brought together representatives from groups ranging from prison operators and service providers, to academics, policy advisers, business leaders, professional services and community groups and services. It is hard to overstate the significance of such a diverse group coming together in a spirit of collaboration and in search of better outcomes.

Our discussions focussed on how we might build support for new approaches in Australia’s criminal justice system. There was broad agreement that addressing the growing incarceration of women was the best place to start. Quite frankly, based on the evidence and lived experiences presented in this report, there is little risk to the community from reducing rates of female incarceration and significant benefit from doing so.

From there, we aim to build momentum for broader reform of the criminal justice system, backed by evidence and supported by political and community consensus.

The jury is in. Data, the criminal justice experts who contributed to this report and recent reports from the Productivity Commission (PC) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) all show that while Australia’s imprisonment rates have been soaring to historic highs, the system is failing. Within two years of their release, more than 50 per cent of prisoners return to either prison or community corrections. This comes at a high cost to both taxpayers and the most vulnerable in our community.

Our soaring imprisonment rates are reinforcing the vulnerability and disadvantage of women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in particular. Compounding these failings, the impacts of increased vulnerability and disadvantage will be felt not just by the current generation, but also by new generations growing up in households disrupted by imprisonment.

The rise in imprisonment is driven by systemic social and policy trends that are multi-faceted, including tougher bail laws, the impact of disadvantage and community and domestic violence, as well as factors such as increased reporting of crime. A tough-on-crime philosophy is also driving increased imprisonment rates, reinforcing the most damaging and disruptive aspects of the current system to peoples’ lives. Over-policing, bail laws and sentencing, as well as a lack of support for released prisoners, are all driving outcomes that are unacceptable and out of step with other advanced nations.

This report also shows that the current trajectory of imprisonment is unaffordable. Nationally, we are now spending more than $5.4 billion a year on corrective services. While state governments have initiated various programs to address recidivism, they are ad hoc and piecemeal. We must change course as a nation – the current approach is not sustainable and does not meaningfully keep our communities safer.

This is especially clear when it comes to women, who are closing the gender incarceration gap at an alarming rate. Most incarcerated women serve short sentences, if sentenced at all. Many spend time in remand and then are either not convicted, or are sentenced to time served or less. Every night a woman spends behind bars for a crime for which she was not convicted, or for which she was sentenced to less than time served, is clearly a waste of taxpayers’ money. More importantly, it severs her links to the community and has an intergenerational effect. In addition to the indirect costs imposed on the children and families of these prisoners, the growing fiscal burden of our justice system has little to show for it in reduced crime rates.

CEDA’s review of the data and literature, and the contributions in this report, show Australia cannot afford to let the economic and human costs of rising imprisonment keep growing. Recent state government initiatives have shown that commitment to action and targeted policy changes can reverse recent trends. The time to act is now.

Closing the wrong gaps: Australia’s rising incarceration rates

Rates of incarceration have been rising in Australia over the last 40 years despite falls in serious criminal activity in the last 20 years. Latest figures from the ABS show there were 370 victims of homicide and related offences, including murder, in 2021 – seven per cent less than reported figures for 2020. Imprisonment rates rose by five per cent over the same period. Between 2003 and 2018, Australia’s imprisonment growth was the third highest among OECD countries, with only Turkey and Colombia showing faster growth rates.

Ember Corpuz

Ember Corpuz joined CEDA in 2015 and is currently leading work in justice, which is a critical institution underpinning economic and social development. Prior to joining CEDA, she worked as an environmental scientist in various private sector and non-profit roles. Her professional experience also includes considerable contributions to state government in the field of climate change and policy development. Ember has a master’s degree in Environmental Management from Flinders University and is completing a doctoral degree at the University of Adelaide’s School of Psychology.

Despite a broader focus on gender equity in key areas such as workforce participation and pay, it is disappointing to observe that women are all too quickly closing the incarceration gender gap, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women the fastest growing group.

The case for change

While overall numbers of female prisoners are lower than men, they have grown by more than 60 per cent over the last decade, considerably faster than growth in the male population. This underlines that over-policing of minor offences, and tougher bail and sentencing laws, are having a disproportionate effect on women. In addition, evidence suggests that women are treated differently when they are in custody and in front of courts, struggling to get needed support. A focus on women will begin to stem growth in imprisonment rates. This begins with increased engagement with vulnerable groups and prioritising the voice of people with lived experience.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported a total of 39,680 male prisoners and 3292 female prisoners in June 2021. Prison populations are growing at a staggering rate, and despite being a smaller proportion of the prison population, the number of women prisoners is rising faster than for males – by 64 per cent over the last decade, compared with 45 per cent for men. Figure 3 (below) shows women are sentenced to custody for comparatively minor offending.

This is a clear reflection of the way our criminal justice system is failing the most vulnerable in our communities – disadvantaged women. We are jailing victims of violence, people with mental health issues, those with drug or alcohol dependency and who lack secure housing.

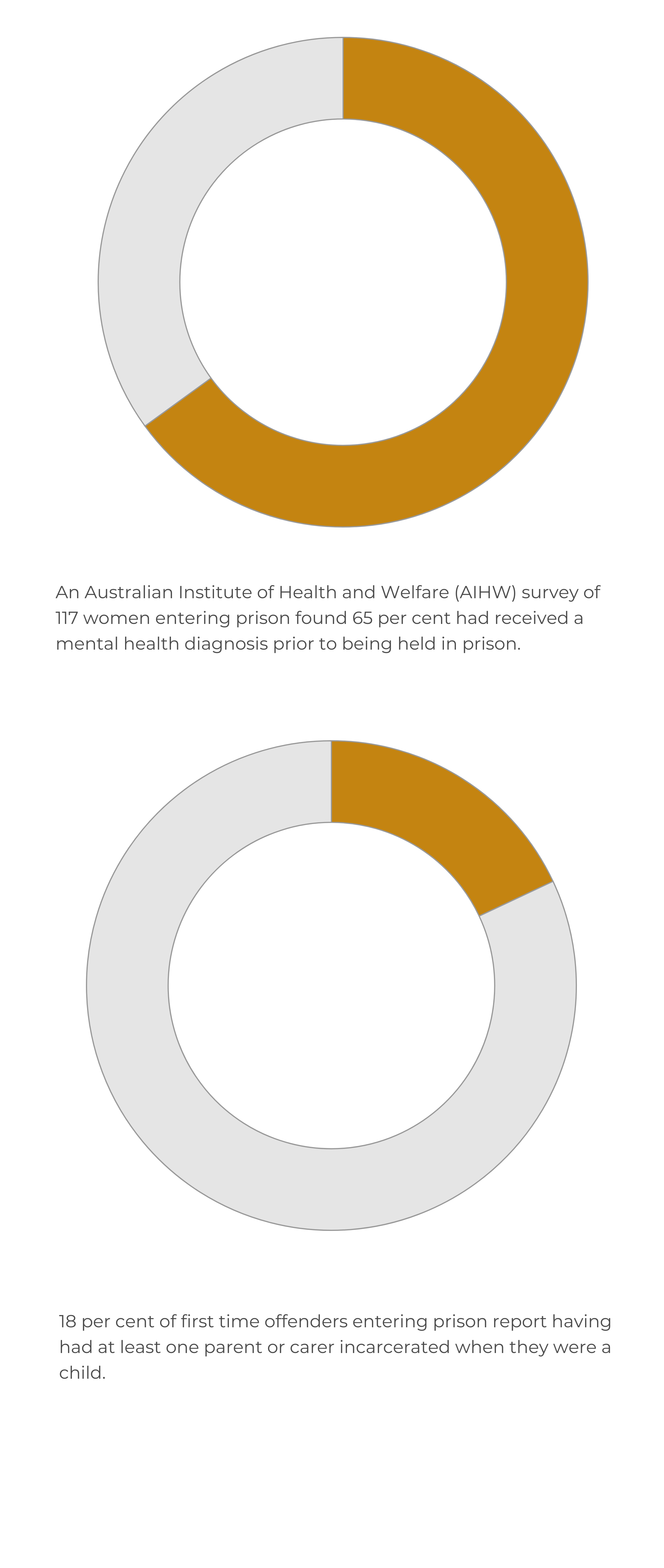

An Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) survey of 117 women entering prison found 65 per cent had received a mental health diagnosis prior to being held in prison.

The Australian Law Reform Commission found Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women were 21 times more likely be in prison than non-Indigenous women. Many already have even greater experiences of disadvantage through intergenerational trauma, having been in state care or the justice system at an earlier age, and/or already experiencing more significant police monitoring for low-risk offending.

A growing number of female offenders are victim-survivors of domestic abuse in poverty and disadvantage. They are usually in custody for breaching community corrections orders or justice orders, such as bail. According to the Women’s Legal Service Victoria in 2019, “police were consistently misidentifying women victims of family violence as primary aggressors”. Police are likely to label women who present as “hysterical” or overly upset as the aggressor, because first responders are unable to identify how coercive control manifests in victims of abuse.

A high proportion of these women present little or low risk to the wider community, as evidenced by the high proportion receiving short sentences of less than six months. Yet many are denied bail and are remanded into the system, only to receive sentences of time served or less.

Short sentences are more disruptive than rehabilitative. Most offender rehabilitation programs run for at least 12 weeks. Some programs specifically targeted for women in prison with a risk of re-offending and substance use run for 16 weeks, which means that those sentenced for four months or less are ineligible. As such, not only do they leave prison traumatised and stigmatised, their connections to family and critical support networks have been severed, making it even harder for them to secure paid employment. Exacerbating the negative consequences of this approach is the adverse intergenerational impact.

A growing prison bill

Making matters worse, taxpayers are footing a growing prison bill for questionable outcomes: crime is not increasing, but recidivism is. In Victoria, 52.5 per cent of prisoners released during 2018-19 returned to corrective services within two years. This is consistent with the national rate of 53.1 per cent. Repeat offenders account for about half of prison costs, which would amount to roughly $2.5 billion.

.png)

Although prisoner numbers decreased in 2020 for the first time nationally since 2011, this is likely an impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the many restrictions implemented by governments. We are now seeing a return to the rapid rise in incarceration rates of 2017.

The above graph shows a five per cent increase in prisoner numbers from 2020. Nationally, we are now incarcerating 44 more people for every 100,000 adults than in 2008. This is concerning enough from a social justice perspective. But the trend also brings significant and escalating costs, from increasing demands on government budgets to lost economic opportunities and costs of poor health for prisoners and their loved ones.

Costs

The fiscal, social and economic costs of incarceration in Australia are significant. The Productivity Commission’s 2022 report on government services revealed that nationwide, governments spent more than $5.4 billion a year on prisons in 2020-21, up 5.1 per cent on the year before in real terms. At this price, taxpayers are spending at least $330 per prisoner, per day. Growth in spending in the justice sector, which includes police, courts and corrective services, is now eclipsing growth in other areas such as health, education, as well as housing and homelessness.

The 2019 Queensland Productivity Commission (QPC) Summary Report on Imprisonment and Recidivism estimated a direct cost of $111,000 per prisoner per year in the Queensland prison population.

Although indirect costs to government are not easily measured, the report estimated these indirect costs would come to an additional $48,000 per prisoner each year. The indirect and sometimes intangible costs of imprisonment include loss of home and employment, mental ill-health and disconnected families, especially parent-child relationships.

It is hard to justify the spending we are seeing, including commitments to build new and larger prisons to accommodate this trend in the future. While there is a need for more long-term analysis, there is robust evidence that alternatives can and should be considered as a better way forward.

Counting the costs

If government spending on corrective services continues to follow recent trends:

- By 2030, governments would be spending more than $7 billion a year on corrective services, using a conservative estimate.

- By 2030, nearly 60,000 Australians would be in prison.

- If we can divert 50 per cent of sentenced women from prison, assuming recent trends in female incarceration rates:

- By 2030, around 4,888 Australian women would be in prison. If we diverted half of them from a custodial sentence, governments would save about $288 million in direct costs that year

- By 2030, governments would save at least $117.3 million in indirect costs that year, using the QPC’s estimate of indirect costs $48,000 per prisoner per year.

Systemic drivers

Key structural drivers of incarceration vary by jurisdiction. For example, changes to the Victorian Bail Act introduced in 2018 made it more difficult for vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals to access bail and parole. The tougher bail law was triggered by a man released on bail before driving though Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne, killing six people. But a considerable number of women and children do not receive custodial sentences. Most of them are on remand and remain there because they were refused bail. When their matter gets to court, even if they are eventually convicted, they receive a time served decision and are released into the community. Due to current bail laws and delays within the court system, the remandees are held in custody for a relatively short but disruptive prison experience that leaves an adverse impact on the lives of them and their family.

While the changes were triggered by an extreme act of violence, they disproportionately affect women and children experiencing entrenched disadvantage. Data from Corrections Victoria in 2020 show women are more likely to be in prison for offences relating to illicit drugs than men, and less likely to be in custody for assault offences than men. In 2020, 43 per cent of women in custody were in remand. The data also reveals that women are more likely to be held on remand than men. Victoria’s prison population in 2021 grew 1.4 per cent from the previous year despite a 5.1 per cent decrease in criminal incidents recorded in the year ending March 2021.

Even prior to the changes to the state’s Bail Act, Corrections Victoria revealed that in 2017, “overall only 17 per cent of women who were initially remanded and then bailed were sentenced to a term of imprisonment longer than the time they had already served on remand”. For those women, experiences in remand have severed their connection to support, housing, employment services and their children. Women are more vulnerable when they are isolated from their community and are more likely to re-offend.

It’s also harder for those who have been released on time served to be granted parole, which is an essential check. Parole can ensure they are supported and supervised so they have a better chance of successful reintegration, rather than being released directly into homelessness, addiction and unsafe relationships, which can increase the likelihood of re-offending.

In Victoria, the number of adult prisoners in custody who had not been sentenced almost doubled in the six years to March 2019 before the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationally, the number of prisoners on remand increased by 16 per cent to 15,182 in 2021. Despite this rise, no published research has been found that examines the extent to which remandees are ultimately convicted of the offences for which they were remanded. Nor does research show the type of sentence they receive if they are convicted. In January, an Aboriginal woman died while reportedly withdrawing from illicit drug use just a few days after being refused bail in Victoria. She was charged with shoplifting.

This again demonstrates how tough-on-crime approaches do not necessarily protect the community from violent criminals, but instead further harm vulnerable women.

There is also limited support and assistance for re-integration back into the community. The 2019 Keeping Women Out of Prison (KWOOP) report revealed that 78 per cent of female prisoners in NSW were released back into the community without any support services in place. In addition, about a third of all female prisoners will be released back into housing instability, if not complete homelessness, increasing the risk of re-offending.

The QPC found that the overall median prison sentence in Queensland was 3.9 months, with 62 per cent of sentences being for non-violent crimes. The report further details how rising incarceration rates are more likely linked to structural changes such as the use of imprisonment in sentencing instead of non-custodial sentences, increased policing efforts and rising re-offending rates, than to actual rates of crime. Penal Reform International (PRI) in its Global Prison Trends 2020 report, found that more women, than men are in prison for drug-related offences. Automatic pre-trial detention, even for possession and other low-level drug offences, thus tends to incarcerate a greater proportion of women. Short custodial sentences exert no more deterrent effect than comparable community orders.

The Australian Law Reform Commission revealed that prisoners serving short sentences were less likely to be able to access programs or training. Time spent in prison therefore does little to address offending behaviour or to develop skills that might later prevent re-offending.

Short sentences of imprisonment:

- Expose minor offenders to more serious offenders in prison;

- Do not serve to deter offenders;

- Have significant negative impacts on the offender’s family, employment, housing and income;

- Are particularly damaging to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women;

- Limit opportunities for offender rehabilitation; and

- Potentially increase the likelihood of recidivism through stigmatisation and the flow-on effects of having served time in prison.

Social drivers and insufficient support services

A great number of women prisoners have been victimised and disadvantaged through discrimination, abuse and domestic violence, mental ill-health, addiction and financial insecurity.

Research shows that a growing number of these women are victim-survivors of domestic abuse who are usually in custody for breaching community corrections orders or justice orders, such as bail. Women tend to be primary carers of their children. Sentencing carers into custody has an impact on their children’s development and mental health. Research has also shown that courts are likely to send a person into custody if the person has already been in prison before. This contributes to a vicious cycle of disadvantage and intergenerational offending. Further, a considerable number of women who flee their homes due to domestic abuse find themselves in temporary or emergency housing. Most have part-time or casual employment and as such are unable to secure stable housing, which soon drives them to homelessness. This can leave them susceptible to activities that will lead them back to prison.

The recent merger of the Family Court of Australia and the Federal Circuit Court of Australia in early 2022 raised concerns among former judges who feared that without a specialist court, more family violence survivors would be left without appropriate legal and social support. A gendered lens in sentencing is required, especially given evidence suggesting that approximately 70 per cent of imprisoned women are victims of crime themselves.

Death of Ms Dhu

- Yamatji woman Ms Dhu was a 22-year-old Indigenous woman who died in police custody in South Hedland, Western Australia, in 2014. On August 2 that year, police responded to a report that her partner had violated an apprehended violence order. The officers arrested both Ms Dhu and her partner after realising there was an arrest warrant for unpaid fines against Ms Dhu. She was ordered to serve four days in custody.

- That evening, she was taken to Hedland Health Campus, with pain in her right lower rib area after being assaulted by her partner earlier that year. She was diagnosed with “behavioural issues” and taken back to police custody that night but was brought back to the hospital in handcuffs the next day.

- On August 4, two days after her arrest, Ms Dhu died after she was brought back to the hospital unconscious. The WA Coroner found the cause of death was staphylococcal septicaemia and pneumonia, with osteomyelitis complicating the rib fracture.

Reversing female incarceration rates

Diversion

In June 2020, Western Australia passed legislation that prevents the sentencing of fine defaulters to prison, except as a last resort. This change was largely prompted by the case of Yamatji woman Ms Dhu, who was sentenced to prison for $3622 in unpaid fines and died in custody in 2014 (see Box 3).

Non-payment of fines does not result in imprisonment in South Australia. However, one receives a summons for fine default and can be incarcerated for being in breach of the summons.

Western Australia abolished sentences of three months or less in 1995 and in 2003 increased the threshold to six months. It is still the only Australian jurisdiction to have done so. There is insufficient data on whether sentence creep has been prevalent following the abolition.

Examining women’s pathways to criminality might be another approach to adopt. For example, a significant number of women are victims of domestic abuse and for several reasons might recant their statements or find themselves reconciling with an abusive partner. Women can be charged for aiding and abetting once a statement is retracted.

Structural change and reformative justice

In New South Wales, a KPMG impact assessment of Australia’s first major Justice Reinvestment project, Maranguka Justice Reinvestment, in the town of Bourke, found there was a 14 per cent reduction in bail breaches and a 42 per cent reduction in days spent in custody. Overall, an estimated economic impact of $3.1 million in 2017 was reported. Given the success of the project in this community, this model can be applied in a different jurisdiction to help further divert women from prison. We can create preventive measures because we know the circumstances that increase the likelihood of offending.

Justice reinvestment

- Justice reinvestment redirects money from prisons towards helping communities rebuild human resources and develop the infrastructure to support preventative measures.

- The process involves the community, government, prison operators, researchers, essential services and other stakeholders.

- The “life course” approach contributed to the success of the program in the Bourke Aboriginal community. Risk factors were identified throughout an individual’s stages of life that enabled the provision of appropriate and preventive support, reducing contact with the criminal justice system.

- The project identified simple issues, such as driver licence offences, and reinvested funding into a learning-to-drive program.

- Other activities include the formation of a Bourke Tribal Council, developing police and community protocols around bail conditions and education-against-violence sessions.

We must also look at how we treat women when they are in custody and in front of courts. A collaborative approach would link individuals to a central hub of service providers and community groups. A process for creating a triage and hierarchy of needs alongside the risk of imprisonment should inform access to services and supports, including legal advice and maximising access to financial supports during times of crisis. Specialist staff and increased training across support services would also be required to produce such a triage system.

Roadblocks to change

Sentencing generally occurs at a state and territory level, resulting in inconsistent outcomes. Reducing female incarceration rates will also require addressing issues of employment and increasing social housing, which are both significant challenges. Moreover, the multifaceted issues driving this problem require co-operation from multiple stakeholders – social services, community groups, government, the private sector, social enterprise and research institutes.

A possible solution may lie in abolishing short sentences – potentially those of less than six months. However, there must be some mechanism that ensures minor offences are not consequently met by harsher penalties. Most women charged with offences live in poverty and are unable to meet bail. For those incarcerated on drug-related and other substance-abuse offences, the option of rehabilitation is not feasible without appropriate funding.

Some women in prison have also reported the personal cost of attending community service. They describe their struggle balancing their caregiving role while also holding down a job, maintaining a home and attending community service. The option of electronic monitoring instead of being sentenced in custody may not be feasible for this cohort, who mostly come from disadvantaged backgrounds. The choice they face would then be between debt or prison. Most would be unable to afford this option. Further, electronic monitoring devices are usually visible, creating stigma for those wearing them.

Next steps

Women are a small but rapidly growing proportion of Australia’s prison population. They are typically incarcerated for low-level offending. When a woman’s connection to her community is broken through incarceration, her disadvantage can be further entrenched. Her absence can also have intergenerational consequences for her children, creating further economic and social costs and an ever-widening cycle of disadvantage.

The data presented here clearly shows that Australia’s tough-on-crime approach is not working. We must divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system, reduce recidivism rates and create sustainable and long-term change by investing in community-led interventions.

There is plenty of evidence showing what isn’t working. What we must now build, working with groups across all relevant sectors, is a body of long-term data showing what does work. Shifting governments from a tough-on-crime approach will be challenging, as will convincing the public to trust the effectiveness of community-based sentences. Australia will benefit both economically and socially from a justice system that not only keeps our communities safe, but also rehabilitates offenders and causes no further harm.

_1.png)

Double jeopardy: The economic and social costs of keeping women behind bars

Download PDF here

We have spent decades fighting against bad laws and bad policies that are hurting our people. Years, advocating for the freedom to practice culture, establish our own services and determine our own futures. As First Nations women, members of our communities and service providers to our people, we are the experts of our own lives. Yet still we struggle to get governments to listen to our demands, non-Indigenous businesses to invest in our initiatives and ally organisations to step back and support our self-determined solutions.

First Nations women have the answers, but are you ready to listen?

The injustices that affect First Nations women are well known - we are 32 times more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence than non-First Nations women, 10 times more likely to die due to assault and 45 times more likely to experience violence. We are being criminalised at an accelerating rate, and are terrorised with the threat of having our children removed. These terrible statistics are well-known. Our frustration comes not just from the years of government failure that fuel these injustices, but from the years that we have put the solutions on the table only to have them ignored.

Bad laws and bad policies lead to bad outcomes

First Nations women are the collateral damage of political law-and-order stunts and knee-jerk policy reform. Punitive bail law reform, custodial sentences for minor offenses and the criminalisation of homelessness, addiction and poverty are driving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women into prisons and trapping women in violent households.

Despite the documented rise in the number of imprisoned women, state and territory governments continue to introduce laws that trap First Nations women in the criminal legal system. Punitive bail laws in Victoria are a clear example of these harmful policies. Introduced in 2018 purportedly to target violent men, instead they are disproportionately levelled against First Nations women, resulting in the incarceration of First Nations women committing minor offenses being incarcerated and held on remand. Victorian Corrections data shows that since these bail laws were introduced, more than half of all women in Victorian prisons are unsentenced. Victoria is not alone. In Western Australia there has been a 150% growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women being held on remand from 2009 to 2016.

These are bad laws and bad policies at the pointy end of the justice system. These decisions are directly responsible for ripping women out of their families and communities and trapping them behind bars. But there are so many decisions and policies further downstream that insidiously steal our autonomy, decision-making capacity and freedom. These are the social security decisions that place First Nations women on income management and below-poverty-level Centrelink payments. They are the housing decisions that prioritise the ability of landlords to make profits over raising revenue to fund adequate public housing. They are the child-protection decisions that remove our babies instead of providing us with support.

Change the Record

Antoinette Braybrook

Co-Chair, Change the Record

Cheryl Axleby

Co-Chair, Change the Record

Sophie Trevitt

Executive Officer, Change the Record

Criminalising poverty and homelessness is criminalising our people

The overrepresentation of our women in prison is both a cause and a consequence of family violence, poverty and homelessness. First Nations peoples are disproportionately forced onto inadequate, below-poverty-line Centrelink payments and into substandard housing. Even more so, First Nations women are forced onto punitive and discriminatory programs such as ParentsNext, which not only fail to provide a sufficient social-security safety net for women to feed and house themselves and their children, but also deprive women of their basic rights through punitive mutual obligations.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have been clear about the way paternalistic welfare policies harm us and our communities - the unlivable rates of payment, lack of cultural safety, the punitive, discriminatory and onerous nature of ‘mutual obligations’ and compliance frameworks, the high proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social security recipients being breached and losing their payments and the racial discrimination at the heart of the Community Development Program.

Instead of providing adequate housing so that women and their children can live safely and with dignity, too often women are forced to choose between remaining in unsafe or violent households or waiting years for public housing to become available. Decades of evidence demonstrate the relationship between homelessness and incarceration, and homelessness and family violence. Consistently research has found that one in three people in prison experienced homelessness in the month before their incarceration. Thousands of women are forced to return to unsafe homes or become homeless every year due to inadequate housing.

At the heart of our struggle for justice is a fundamental denial of our basic rights - to live with safety and dignity in a secure home, free from violence. Punitive and discriminatory government policies have put this modest aspiration out of reach for so many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women - forcing us into poverty, prisons and unsafe homes.

Photo credit: @buffie.creative

Our communities, our culture, our solutions

Government decisions have led us here, and now they need to get us out of here: by stepping up in delivering essential services and stepping back to hand us the decision-making power over our own lives.

For too long, Government policies have treated us as a problem to be solved - and not as the source of cultural strength, lived experience and expertise to design and implement early intervention, prevention and support services by and for our people. This doesn’t mean just funding one program, or one service. It means recognising the wealth of knowledge, culture and community connections held by First Nations women and people and investing in our expertise to develop our own business, economic opportunities and social enterprise. It means adequately funding our specialist legal and family violence prevention services. It means removing the government-imposed barriers to our people thriving, such as punitive poverty payments and inadequate, insufficient housing.

We have laid out a blueprint for what’s needed to reduce the disproportionate rates of violence against, and incarceration of, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in our report Pathways to Safety. Prioritising place-based, community-controlled services designed and delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is an essential part of a holistic self-determined strategy to reduce violence and achieve healing, greater community strength and community-led economic development.

What we need now is governments and allies to listen to our solutions and back our plan for safety, equality and justice.

Elena Campbell: Policy Perspective

For more than a decade, Victoria has experienced a devastating increase in rates of incarceration of women. Reforms intended to address serious violent offending have instead disproportionately impacted low-level offenders – those propelled into contact with the system by their own experiences of trauma; those for whom even short periods in custody only entrench this harm.

Though acute, the Victorian statistics are not outliers. A global upwards trend in the imprisonment of women has seen the international community recognise the need for non-custodial alternatives, while similarly recognising the economic costs of incarceration as this welcome CEDA paper explores.

Too often a footnote in this wider discussion, however, is the impact of the incarceration of women on the next generation. Studies indicate that a significant proportion of imprisoned women have children and are more likely than men to be a primary carer.

Yet despite clear evidence that children with incarcerated parents are more likely to enter the out-of-home care and justice systems themselves, Australia does little to identify the existence and needs of these children or to stem this trajectory.

In fact, corrections systems collect little data about women’s status as mothers and the impact of this separation from their children, something that women experience as “double punishment”. Researchers highlight the failure to take children into account from the time of a parent’s arrest through to a parent’s release, with “no processes or protocols to consider or support children” and “a generalised sense that children are someone else’s responsibility”.

Despite the lack of corrections data, wider evidence establishes that women who have lost custody of their children are at higher risk of self-harm and more likely to reoffend than women whose connection with their children has been supported. Evidence also establishes that children whose parents had contact with the criminal justice system are “at risk of poor development across all developmental domains” while children can also be exposed to increased violence, sexual abuse and neglect in the custody of a violent father if their mother is in prison, meaning that out-of-home care is not the only risk.

Compounding this challenge, political cycles generally focus on the short term, despite the ripple effects of kneejerk policy responses being felt for decades to come. These impacts are more fully explored in the Centre for Innovative Justice (CIJ) submission to the Victorian parliamentary Inquiry into Children Affected by Parental Incarceration.

We must look to the long term by reversing current incarceration rates and laying foundations so that they do not rise again. The CIJ’s Women’s Justice Reinvestment Strategy offers a blueprint for these foundations that could be adapted in different contexts to ensure that we stop using custody as a proxy for care in the community and that the mistakes of this generation do not continue to be visited upon the next.

Centre for Innovative Justice, RMIT University

Elena Campbell

Associate Director – Research, Advocacy and Policy, Centre for Innovative Justice, RMIT University

Dorothy Armstrong

Advisor, Lived Experience Consultant and Peer Mentor, Centre for Innovative Justice, RMIT University

Dorothy Armstrong: Lived experience

Before I went into custody my children and I were in transitional housing because of the abuse we suffered. Then my ex-husband took off with the kids, literally moved overnight, and I was distraught. I met another man who completely trashed my housing and I wasn't able to go back because of him. I had no options left to me and I ended up being charged and in prison.

Initially I didn't know where my ex-husband had taken my children, even though there were Family Court Orders. I have brain damage because of abuse that I've suffered and I was quite nonverbal when I got to prison. I wasn't able to communicate with anybody as I was terrified of being hit again. All I could think was, ‘I could die’. Especially seeing all the concrete and steel.

When I first went into prison, I got no help contacting my children. Nobody asked if I had kids, or where they were. Meanwhile, my children thought I was potentially dead, ‘Where's Mum? She's just disappeared off the face of the earth’. Eventually my ex-husband said ‘your Mum’s in prison’ and it was never discussed again or explained. All they could think was that I’d abandoned them.

Prison is about processes, even your telephone contact list. It was months before I could make a call and, when I did, my ex-husband would decide whether I could speak to the kids. Seven minutes with my son, seven minutes with my daughter, often there’d be yelling in the background and I'd be asking everyone around me, ‘I'm trying to speak to my daughter, could you please be quiet?’ My daughter was so worried she’d miss my calls that she stopped doing things, just stayed at home waiting. When I couldn’t call, they were scared that something had happened, that I’d died. They were living with that traumatisation over and over again.

Once my daughter rang the prison and asked to speak with me. The person on the phone asked her what her Mum’s CRN was – I was a number and my daughter didn’t know the answer. She was a child, sobbing, just wanting to speak to her Mum, and they wouldn’t let her.

My kids got no support, they were bullied at school once people found out where I was. They ended up living out of home, in halfway houses and other places, in their early teens because of all the trauma they experienced.

Once I was released, I was kicking in doors trying to get help for me and my children, but it didn’t happen. I didn't get help with connecting with my children.

If my children had somebody to support them, to listen to them and talk with them, that would have made their lives so much better. They probably would not have suffered as much as they have. We’ve had to piece our lives back together – bumping our way through.

My children are the most important thing to me in the world and if there's any kind of opportunity to advocate for children to see their parents in custody, I'll do it forever.

If a woman goes into custody, she should be able to communicate with her children and make sure her children are notified where their mother is. Children should be able to talk with and see their Mum, be able to touch and hug and kiss and have some kind of meaningful activity, normalise the relationship. Just as importantly, set up supports while Mum is in prison that will continue once she's out of prison that are about keeping that family together.

My children's lives were deeply, seriously and severely impacted - because this one person went to prison, their whole life changed. There was no support for them and that has caused damage to our relationship, it is still like climbing a mountain. As my daughter said, you can’t just take a Mama away from her children and then put them back and expect everything to be fine. It doesn’t work like that.

It’s amazing that my kids and I have got to where we’ve got to, but we’ve done it on our own. This is going to be an ongoing conversation, trying to rebuild different bridges that had Molotov cocktails thrown at them. We're all still being affected in ways we're not even really aware of.

Try to imagine how you would feel, how your children would feel, if one day you were there and the next day you’re not and they don’t know what’s happened, never knowing if you’re still alive. It would rip you apart and completely destroy your children.

The people who make the decisions about these things have no idea the effect that it’s having. We could be doing so much better so that children are not the ones paying the price. Whatever way you’re looking at it, you need to change the game radically because it doesn't work. It doesn't just harm the person in custody. It harms their whole family in ways you can't even imagine.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia’s imprisonment rate had risen to its highest level in over a century. Rising imprisonment rates are almost a uniquely Australian story – only two countries in the world, Turkey and Colombia, saw a greater growth in imprisonment between 2003 and 2018. The level of incarceration in Australia is higher than all of the countries in Western Europe and Canada. And while women represent a small minority of the overall prison population in virtually every country in the world, the number of incarcerated women in Australia increased by 67 per cent between 2010 – 2020. What does this increase tell us about the use of incarceration in Australia? Why do we incarcerate so enthusiastically compared to other places, and why are the rates of incarceration increasing so dramatically?

Crime rates in Australia have been stable or decreasing at the same time as imprisonment rates have been soaring. However, there is no causal relationship between imprisonment and crime. That is, increasing imprisonment rates are not able to be explained by increases in crime, and decreases in crime are not able to be explained by higher rates of incarceration. A recent in-depth analysis of crime in Australia, shows in fact that imprisonment has no significant impact on crime rates. Crime and imprisonment are instead impacted by interrelated shifts in the economic and cultural landscape, and social and justice policy. So, if crime rates are falling, what exactly are we using prison for in Australia? And why are we locking up so many more women?

Justice Reform Initiative

Dr Mindy Sotiri

Executive Director, Justice Reform Initiative

In many places around Australia, the increase in the prisoner population has been driven by an increase in numbers of people on remand. Remand populations (that is, people who have not been convicted of any offence and are waiting for their court date, and people who have not yet had their sentence determined) now constitute more than a third of all people in custody. The increase in the remand population is intimately connected to changes to bail legislation, particularly the tightening of eligibility for bail. Policies that tighten bail legislation, alongside policies that tighten eligibility for parole, and policies that increase sentence lengths, have all contributed to our increasing prisoner population.

Decisions around parole, bail and sentence length tend to be made in highly politicised environments, often very quickly, and often on the back of a very public and very serious crime that quite understandably has caused community outcry. However, what is now very clear, is that policies that are made this way (alongside policies that occur in the ‘tough on crime’ law and order auctions during election time), fail dramatically when it comes to building safer communities. Instead, what these policies do, is increase the numbers of people – particularly women – that are captured in the net of the criminal justice system.

For instance, in 2017, 41 per cent of women in Victoria’s prisons were unsentenced and held on remand, typically for non-violent offences. Just a few years later, this figure climbed to 56 per cent, driven in large part by the introduction of tougher bail laws following the Bourke St rampage that killed six people.

When governments restrict access to bail, lawmakers are not intending to lock away more women, many of them vulnerable and with no prior prison history, for offences for which they had not yet been convicted. But the unintended consequences of these changes in Victoria are replicated around Australia. Policy shifts intended to keep the community safer in response to rare but horrific acts of violence, inevitably end up drawing much larger numbers of people into the justice system, not because they are ‘dangerous’ but because they can’t make bail.

The failure of incarceration

The Productivity Commission noted in its report last year that the justice system is failing at enormous expense to taxpayers. This report joins more than three decades’ worth of government-led reports and inquiries in Australia that have identified the failure of imprisonment to achieve its intended crime control ambitions.

Decades of evidence shows us that for the vast majority of people, imprisonment doesn’t work to deter or to rehabilitate. Prison is in fact ‘criminogenic’. The experience of going to prison makes it more likely that someone will go on to re-offend and return to prison. More than 50 per cent of people who leave prison return within two years. If we were to take a snapshot of the prisoner population today, we would see in some Australian jurisdictions, that more than 70 per cent of people currently in prison have been there before.

Although prison works fairly well to ‘incapacitate’, (that is while people are in prison they are not able to commit crime in the community), any crime control function that this might have is generally short term, and then ultimately erased by the fact that the experience of imprisonment increases the likelihood of future offending and imprisonment. Although locking people up in prisons may prevent some crime happening while people are locked up, it does not address the drivers of incarceration, and it certainly doesn’t reduce the likelihood of future crime being committed when people come out of prison.

Alongside the decades of reports showing imprisonments failures to reduce crime, there are countless reports, inquiries and royal commissions that have detailed the damage and harm that prison causes to both those who are locked up, and to the families, loved ones and communities who are also exposed to this experience.

Our over-reliance on incarceration as a default response to both disadvantage and offending has resulted in a situation where too many people in the justice system are unnecessarily trapped in a cycle of harmful and costly incarceration. Instead of reducing the likelihood of reoffending, prison entrenches existing disadvantage and increases the likelihood of ongoing criminal justice system involvement, often over generations. Many people leave prison homeless, jobless, and without the necessary supports to build healthy, productive, connected and meaningful lives in the community.

Australia spends more than $5.2 billion each year on operating prisons and many more billions on building new prisons and new prison infrastructure. When we look at the failure of incarceration to make the community safer alongside the enormous economic and human costs of incarceration, it becomes clear that there is a need to do things differently. We need to take a clear-eyed and evidence-based approach to criminal justice, forming policy and practice around what works – not what is popular or based on kneejerk reaction.

Shifting the political landscape and increasing public education

Across the country, governments on both sides of politics have regularly adopted a ‘tough on crime’ approach to justice policy which has resulted in increasing numbers of people in prison. Although these kinds of approaches can be politically popular, they have been extraordinarily ineffective at reducing cycles of incarceration, ineffective at building safer communities and excessively expensive. The research is clear. Imprisonment is failing. And there are alternatives that work better to keep the community safe. It is not an absence of research or evidence that is holding us back from making long over-due changes; it is an absence of political will. The Justice Reform Initiative was formed precisely because of the need to increase both the political appetite to try something different, and the need to educate the community about imprisonments failures, at the same time as promoting evidence-based alternatives.

While policies from governments of both political persuasions have historically led to poor outcomes in the criminal justice system, the failures of our justice system are not inevitable. There are compelling examples around Australia of evidence-based programs, policies and services that are working to disrupt criminal justice system involvement. There are opportunities to build pathways out of the justice system and improve our service delivery response at every justice system contact point. There is the need to significantly scale up programs in the community and expand the capacity of the community sector to enable people who are caught in the justice system a range of opportunities to genuinely re-build their lives.

While there is no single ‘reform fix’ to reduce prison numbers, there are multiple proven, cost-effective reforms that can work together to make progress. Some of these reforms involve legislative change (for instance Raising the Age of Criminal Responsibility) and some require significant resource allocation to increase genuine alternatives to the justice system so that people have the opportunity to be supported and connected in the community, rather than being ‘managed’ in the justice system. Many of these reforms are already catalogued in an abundance of government and non-government reports and reviews. In addition, there are clear examples and case studies both Australian and internationally that point to approaches led by the community and health sectors that can make a profound difference in disrupting entrenched criminal justice system trajectories.

There is also a growing body of more formal research exploring the impact of various models of support There is clearly the need for early intervention, and community-based support and services that work to prevent people at risk from entering the justice system. There are also then opportunities for diversion at the point of policing, and courts, and multiple options in terms of diversionary and post-release services that are focused on supporting people who have already experienced justice system involvement and are at risk of ongoing justice system involvement.

We need all sides of politics to put aside grandstanding and populist rhetoric, and instead embrace evidence-based justice policies that genuinely address the drivers of incarceration. Jailing is failing – and Australia is increasingly on its own in the developed world in persisting in this failed approach.

In South Australia, Workskil Australia is the sole provider of the Work Ready, Release Ready (WRRR) program which is funded by the South Australian Department for Corrections and commenced in 2018. This program was part of an overarching ‘10by20’ strategy to reduce reoffending by 10 per cent in South Australia by 2020, which has now been achieved.

This program is discussed below in relation to female participants in South Australia, as well some of the systematic issues faced by women in prison and how the program addresses some of these concerns.

Systematic issues facing women in prison in South Australia

Women have higher remand rates than men in South Australia, but shorter sentences. Fifty per cent of women serve less than 30 days in prison and more than 80 per cent serve six months or less. This ‘revolving door’ of women in and out of prison also means additional in-prison support services, like WRRR, are less likely to have a meaningful connection to incarcerated women and result in long-term change.

Workskil Australia

Nicole Dwyer

CEO, Workskil Australia

The primary offence for both Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal women are Offences Against Justice Procedures, followed by Assault as the next most common offence in South Australia. Offences Against Justice Procedures include breaches of Parole and Home Detention, and correlates with the shorter sentences seen for women. Women who have breaches of Parole and Home Detention are often in unstable housing, experiencing domestic family violence or drug use, and these are contributing factors to this offence type.

The general tightening of bail laws that were intended to target violent men, may also be having unintended consequences on women and their remand rates (Australian Institute of health and Welfare, 2020).

High representation of Aboriginal women in custody is well above the general Aboriginal population in South Australia. A 2021 Custodial Admission Program was commenced by the Adelaide Women’s Prison and in partnership with the SA Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement. This Program provided immediate legal representation and collected improved data on new Aboriginal women to custody, in relation to housing, domestic violence, offence type, drug/alcohol use and caring responsibilities. This program is a step in the right direction, but a significant amount of work is required to reduce the number of Aboriginal women in incarceration. It is very good to see a reduction in incarceration rates for Aboriginal prisoners now a Closing the Gap target.

More work needs to be done around supporting pregnant prisoners, and those who give birth while in prison. Every state has different policy settings in relation to the removal of babies and the support provided for female prisoners. There are many positive examples here in Australia and overseas that show improved outcomes for these children and their mothers if they can remain with their mothers, with parenting support.

Work Ready, Release Ready

This is an innovative, voluntary and first of its kind program nationally that commences with case management services in-prison and follows the prisoner as they progress through various correctional facilities during their incarceration period, and literally picks the participants up at the gate on exit and supports their transition post-release for up to two years. South Australia has seen a significant improvement in reoffending since this program has commenced.

The overarching goal of WRRR is to reduce reoffending (with participants followed two years from release) and the achievement of paid employment. A training plan is undertaken with each participant upon commencement in the program approximately two years from release, so that they use their time to participate in training or industry programs while in prison, based on their capacity and labour market opportunities. A release plan is undertaken six months from release. This is a detailed plan on what the participant will do once they are released, with regard to housing, health support, employment, transport and so on, followed by intensive vocational and personal support by a trusted mentor for up to two years after release. This is a voluntary program and candidates are selected on the basis of low education and qualifications, poor work history and most likely to require support with employment upon release.

Female Participants in WRRR

WRRR engages closely with the Adelaide Women’s Prison and has achieved positive results in reducing female re-offending in South Australia. Workskil Australia has supported 1400 prisoners in WRRR since 2018, until 30 March 2022, with 185 (13.3 per cent) of this group women and 62 (17 per cent) of these women identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

A significant amount of focus for women in WRRR is re-connecting them to their children upon release, finding them a safe place to live, helping them to establish a support network on the outside that will be positive for them, and helping them manage their finances, life administration, and to set up their new living arrangements. Many women upon release have poor literacy and digital literacy skills, and support is provided to arrange Centrelink and other services.

WRRR data demonstrates that success in employment upon release is a statistically significant factor in an ex-offender woman not returning to custody. Figure 8 (below) shows women engaged in WRRR who are released and voluntarily remain in the program upon release and gain work are less likely to return to custody.

The WRRR program has reduced recidivism by women in South Australia since it has commenced. The program goes a long way to addressing many of the systematic issues described above and continues to be successful. A lack of affordable housing options is now emerging as a critical issue for women on release and will be the next challenge to work through.

| Returned to custody at least once in 6 months | Returned to custody at least once in 12 months | |

| Amongst all WRRR women participants: | ||

| Placed in employment at least once | 13.3% | 30.8% |

| No known employment placements | 35.0% | 71.4% |

Case Study – Michelle* WRRR Participant

Michelle, an Aboriginal woman in her early 40s, has been in out and of prison since she was 12. She estimates she has been incarcerated approximately 50 times as a juvenile and 10 to 12 times as an adult. She had never worked in paid employment or achieved her drivers licence. Michelle experiences mental ill health and has a long history of substance abuse.

Michelle commenced Work Ready Release Ready in 2020, while incarcerated. She was assigned a mentor, also a woman, who she engaged well with, and they planned her release in detail. Once released she was supported with clothing, housing, health, financial and addiction support. Getting her appropriately assessed with Services Australia was also critical. She gained her Learners Permit and commenced driving lessons, employment services support and a Traffic Management Course.

Over a 12-month period she stabilised, achieved her driver’s licence and gained employment as a Traffic Controller – her first ever paid employment. She reflected that the thing she was most proud of was her ability to drive her mother to appointments, and felt she was able to give something to her family. She remains out of jail currently, the longest period she has remained out of jail in her life.

WRRR supported her for an 18-month period.

All too often, women from marginalised backgrounds are incarcerated without a full understanding of the causes of their offending or the effects that incarceration will have on their future. Reducing rates of incarceration and reoffending is a paramount access-to-justice issue, but with competing social values and policies, and ingrained systemic injustices, it’s also one of the most complex issues facing advocates, researchers, designers and policymakers.

Identifying opportunities to create equality and financial stability for people in prison

We collaborated with Thriving Communities Partnership to better understand how to build financial stability for people in prison, a group of people who are notoriously underserved and disadvantaged by existing financial management systems.

A disproportionately large percentage of the prison population has experienced and continues to experience disadvantage. This includes homelessness, low levels of education and trauma as well as physical and/or mental health challenges. Not only do these disadvantages influence a person’s likelihood to become incarcerated, they also form barriers that people must overcome in order to build financial stability. People in prison often experience ‘hidden debts’, which can quickly grow to unmanageable levels. It is not uncommon for people in prison to have cars, houses and personal items repossessed to cover their debts, leaving them in a worse position when they leave prison.

Portable

Luke Thomas

Senior Legal Designer, Portable

Our research partnership focused on community collaboration and human-centred design. We spent time quantitatively researching the challenges facing people in prison by speaking with 22 people who were currently incarcerated or had previously been in prison through individual interviews and group think tanks. As a result of these discussions, we ensured the range of human experience and stories we heard could be communicated through our design artefacts (personas and journey maps) that would inform Thriving Community Partnership’s ongoing research and collaboration with the financial sector. Our goal was to create artefacts that would enable anybody, regardless of their level of subject matter expertise, to empathise with the experience that someone who is currently or has been incarcerated might have had.

Applying co-design to rising incarceration rates

Including communities in the research and design process involves understanding the context of the problem, and hearing from the people involved. There is a wealth of research into the incarceration of women, providing insight into the ways violence against women perpetuates cycles of generational incarceration, or rethinking the response to female offending. This echoes the need to understand the root causes of offending behaviour and the need for more holistic, empathetic approaches. Over the past few years, we’ve spoken to court officers, judges, legal aid, police and women who are currently incarcerated or recently released.

Many people in prison come from severely disadvantaged backgrounds with serious physical and mental health challenges and higher rates of disability than is found in the general population. Incarcerated women are disproportionately represented in unemployment, health and homelessness statistics. For instance, it’s estimated that 33 per cent of women in prison have an acquired brain injury (ABI), compared with two per cent of the general population. People we spoke with who have experienced issues with debt, homelessness, health or ABIs pointed to the lack of integrated services that would have helped them resolve the issues they were experiencing before they committed the minor offences that led to cycles of reoffending.

Rates of reoffending as well as personal accounts of the prison experience indicate that incarceration isn’t effective rehabilitation. In 2020, more than seven in 10 (72 per cent of) prison entrants who were women had previously been in an adult prison. Women we spoke with during our research into barriers affecting financial stability who had experienced family violence felt that the loss of control and independence perpetuated by the prison environment made them feel isolated and unsafe. This led to them being unable to build new connections or receive the support they needed to overcome cycles of violence and trauma. The intergenerational cycle of trauma is a systemic issue that disproportionately affects women and First Nations communities. For many women, incarceration affects their ability to care for or spend time with their children, further contributing to an ongoing cycle of trauma, criminal activity and incarceration.

Understanding the root causes and the levers to bring about systemic change is vital to creating approaches that take into account the various factors, needs and motivations of everyone involved. In the context of increasing female incarceration rates, this means looking for opportunities to address cycles of violence, intergenerational trauma and disadvantage through connected, holistic services.

Community-based approaches to justice address both the huge cost differential between incarceration and community programs as well as the need for empathetic responses to complex issues. Alongside the economic advantages, choosing community-based outcomes enables women to access support programs, financial resources or medical and psychological support without being exposed to further violence and trauma. Understanding the need for new approaches and service interventions is only the first step, as new approaches also need to be piloted, tested, evaluated and scaled to address this important challenge.

.png)