PROGRESS 2050: Toward a prosperous future for all Australians

06/12/2020

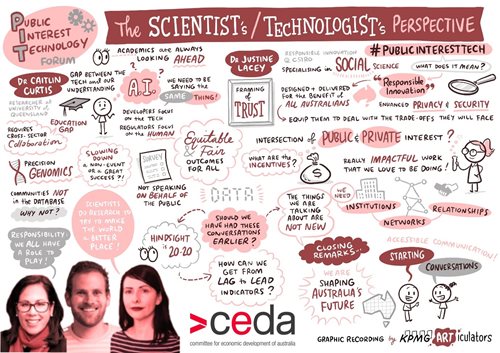

Throughout the opening sessions of CEDA’s Public Interest Technology forum, the role and responsibility of  technologists in regard to responsible or ethical tech development and design, and in earning trust in emerging technologies was touched on. This session focussed squarely on these issues with insights provided by Dr Caitlin Curtis of the University of Queensland’s Centre for Policy Futures and Dr Justine Lacey, Director of Responsible Innovation Future Science Platform at the CSIRO.

technologists in regard to responsible or ethical tech development and design, and in earning trust in emerging technologies was touched on. This session focussed squarely on these issues with insights provided by Dr Caitlin Curtis of the University of Queensland’s Centre for Policy Futures and Dr Justine Lacey, Director of Responsible Innovation Future Science Platform at the CSIRO.

The very clear message that emerged through this conversation was that scientists and technologists do have a professional responsibility for the technology they develop and its impacts, but that there is nuance and complexity in understanding the limits of that accountability, how it is delivered and who else shares accountability. Justine noted that it is too simple to conclude that accountability for responsible tech or innovation lies solely with technologists not least because that assumes technologists have the power to shape the entire complex system into which that technology is landed.

A 2019 survey conducted by CSIRO confirmed that scientists and researchers felt a professional responsibility to advance a science-society relationship, and knowing what is going on in the world, using that to inform science, is important to advancing that relationship.

Both speakers underscored the importance of communication and transparency, open conversations around risks (as well as benefits) and understanding community expectations. Relevant to these considerations, Caitlin noted that conversations about what is in the public interest, how to achieve it and who is responsible would benefit from getting everyone on the same page – or at least closer to that. Key challenges in that regard are that, based on research conducted by the University with KPMG on trust in AI, the community overall has a relatively low understanding of AI and where it is used (even in regard to everyday activities such as the use of email and social media). In addition, policy makers and developers often use different definitions, which means even when they think they are talking about the same thing they may not be. Similarly, with technology moving quickly, different groups can view governance priorities differently. For example, computer scientists and engineers in the US have been found to place less emphasis on the governance risks of AI than the general public.

Programs to increase public awareness and understanding of emerging tech would facilitate better engagement and understanding of community expectations. Caitlin noted an interesting model developed in Finland.

Justine also noted the significance of shifting expectations, observing that societal expectations about ‘having a say and being heard’ really started to emerge from the 1960s.

Caitlin highlighted the benefits of business communicating around innovation and their use of technology, particularly given that people perceive corporate innovation to be driven more by financial benefits that societal good. Taking this a step further, Justine suggested that there was scope to see an intersection of public and private interest (ie that they need not always be in conflict) in the sense that business could use its commitment to (and demonstration of) socially responsible development of technology as part of its reputation and brand.

In terms of areas for future opportunity, Justine drew attention to the importance of developing lead indicators related to the impact of technologies, to allow us to effectively ‘cast forward’ the implications of technologies.

Both Caitlin and Justine endorsed the value in collaborative efforts to build capability and train the next generation of scientists and researchers with a focus on practical applied, and broad capabilities (as CSIRO is already doing with three universities) and to work with people in broader disciplines (law, human rights) to build two-way knowledge and understanding. The Public Interest Technology University Network in the US might prove a useful model.

Watch this discussion

KPMG live-scribe

CEDA's PIT Forum was supported by our Foundation Partners: