Explore our Climate and Energy Hub

Back to all opinion articles

16/09/2018

Unemployment benefits and a range of other payments haven’t kept pace with Australian living standards over the past quarter of a century.

What if we undid that? The Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) asked Deloitte Access Economics to model a ‘catch up increase’ of $75 a week for the least well off in Australian society. Our results show what would happen to both prosperity (the size of the pie) and fairness (how the pie is sliced up).

That gradual rise in interest and exchange rates see the benefits to the economy fade over time. More importantly still, this policy change comes at a cost to the federal budget, which the modelling assumes is eventually repaid. That combination of factors gradually returns the Australian economy towards the path it would have otherwise been on. Or, to put that another way, the prosperity benefits fade over time.

That said, the modelling probably understates the extent of these prosperity benefits. For example, higher incomes for the unemployed and other disadvantaged groups may lead to better national outcomes on indicators such as mental and physical health.

Similarly, the economic literature has increasingly identified inequality as a factor that can directly weigh on prosperity. For example, research by the IMF indicates that:

The two largest fairness levers in Australia are (1) cash benefits and (2) the operation of the education and health systems. Our report considers the impact of potential increases focussed on the unemployment and study payments category of cash benefits.

The analysis shows that the bulk of the dollars go to the lowest income quintile of households – the bottom fifth. Measured in dollar terms, that group receives six times the dollars going to the highest income quintile.

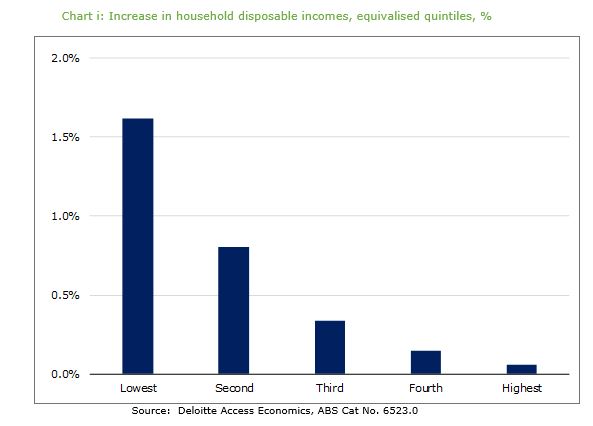

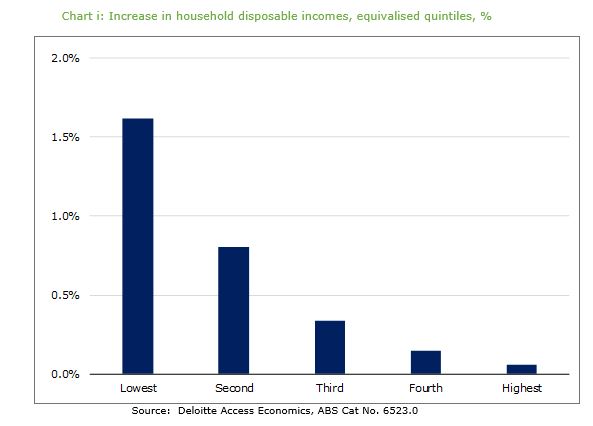

That said, dollars aren’t necessarily the best way to assess the impact on fairness. What matters is the relative impact of those extra dollars on disposable incomes. And, on that measure, the proportionate impact becomes fully evident. As the chart below shows, the lowest quintile would receive 28 times the relative boost to its disposable income than does the highest income quintile.

Accordingly, any given dollar spent on this policy proposal would have a very tightly targeted fairness impact, with the overwhelming bulk of relative improvements in disposable income going to Australia’s lowest income families.

Doing something about that would benefit the least well off in Australia in a tightly targeted way (with very few of the benefits going to higher income households), providing a boost to the Australian economy at the same time.

What if we undid that? The Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) asked Deloitte Access Economics to model a ‘catch up increase’ of $75 a week for the least well off in Australian society. Our results show what would happen to both prosperity (the size of the pie) and fairness (how the pie is sliced up).

The prosperity dividend for the Australian economy

A lift in allowances – an extra $10.71 a day for the more than 770,000 people who receive the single rate of one of these payments – would directly cost the federal budget about $3.3 billion a year. But the Australian economy (the prosperity dividend) would grow by about $4.0 billion:- The extra income goes to those who are most likely to spend it, particularly on essentials such as food and rent – meaning that consumer spending would lift by some $3.3 billion.

- That would generate 12,000 extra jobs, and the accompanying strength in the market for workers would lift wages too. (Prices would also be a little higher, but the increase in wages would outweigh that in prices.) Corporate profits would also increase.

- Finally, the stronger economy (more jobs, higher wages, stronger profits) would mean that the Federal Government would raise an extra $1.0 billion in taxes, while state and territory government revenues would increase by some $0.25 billion.

That gradual rise in interest and exchange rates see the benefits to the economy fade over time. More importantly still, this policy change comes at a cost to the federal budget, which the modelling assumes is eventually repaid. That combination of factors gradually returns the Australian economy towards the path it would have otherwise been on. Or, to put that another way, the prosperity benefits fade over time.

That said, the modelling probably understates the extent of these prosperity benefits. For example, higher incomes for the unemployed and other disadvantaged groups may lead to better national outcomes on indicators such as mental and physical health.

Similarly, the economic literature has increasingly identified inequality as a factor that can directly weigh on prosperity. For example, research by the IMF indicates that:

- Nations with greater levels of inequality tend to have lower economic growth over time (in the language used in this report, failures on fairness can limit success on prosperity); while

- The worse is inequality in a nation, then the shorter are its spells of high economic growth.

And what of the impact on fairness?

The most compelling reasons to adopt this reform revolve more around fairness than they do around prosperity.The two largest fairness levers in Australia are (1) cash benefits and (2) the operation of the education and health systems. Our report considers the impact of potential increases focussed on the unemployment and study payments category of cash benefits.

The analysis shows that the bulk of the dollars go to the lowest income quintile of households – the bottom fifth. Measured in dollar terms, that group receives six times the dollars going to the highest income quintile.

That said, dollars aren’t necessarily the best way to assess the impact on fairness. What matters is the relative impact of those extra dollars on disposable incomes. And, on that measure, the proportionate impact becomes fully evident. As the chart below shows, the lowest quintile would receive 28 times the relative boost to its disposable income than does the highest income quintile.

Accordingly, any given dollar spent on this policy proposal would have a very tightly targeted fairness impact, with the overwhelming bulk of relative improvements in disposable income going to Australia’s lowest income families.

The bottom line

A policy mistake that’s now a quarter of a century old has seen a dramatic slip in the relative living standards of those on unemployment benefits and some other allowances.Doing something about that would benefit the least well off in Australia in a tightly targeted way (with very few of the benefits going to higher income households), providing a boost to the Australian economy at the same time.

CEDA Members contribute to our collective impact by engaging in conversations that are crucial to achieving long-term prosperity for all Australians. Find out more about becoming a member or getting involved in our work today.