Australians deserve to age with dignity.

As more Australians enter old age, we have failed to prepare for the human challenge at the centre of aged care by building a workforce that is both big enough and well-equipped to meet community expectations.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety made many good recommendations for reforming the sector but did not have enough focus on practical ways to increase the workforce. We have made 18 recommendations to address this workforce challenge. Many build on those of the commission, but with greater detail and clearer outcomes. Extensive consultation with industry experts, aged-care providers, training organisations and unions informed our analysis and recommendations.

We require 17,000 more direct aged care workers each year to meet basic standards of care

Demand for aged care workers is increasing

Where do we find the aged care workers we need?

Workers may join the sector from three primary sources:

1. Training;

2. Migration, noting that around 30 per cent of the current workforce is made up of migrants;

3. Staff moving from other sectors or returning to aged care, most commonly from adjacent health and social-services workforces.

But any gains from these three sources will be offset by workforce attrition. The size of the workforce could be increased by policies to encourage inflows and/or improve attrition rates. Using an assumption of 18 per cent attrition, based on available research and consultation, the industry needs a gross annual increase of around 65,000 workers. At current rates of trainee completions and migration this leaves a huge gap in workers required.

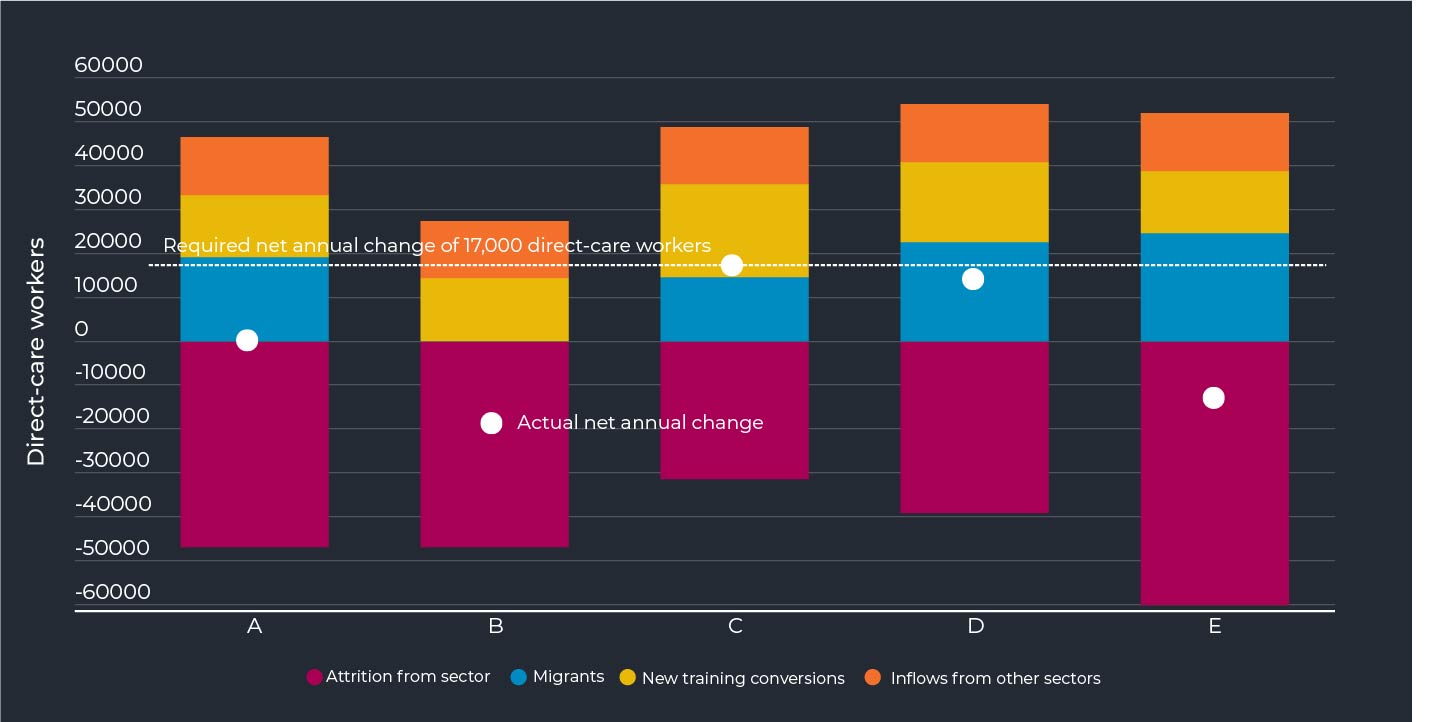

CEDA has constructed five scenarios that illustrate the impact of any changes to the three key sources of workers

A. Continuation of recent trends for attrition, migration and new training completions.

B. Continuation of recent trends but no migration (as currently experienced).

C. Reducing attrition to 12 per cent and increasing training completions by 50 per cent.

D. Reducing attrition to 15 per cent, increase training by 30 per cent and increasing migration by one-third.

E. Continuing on the current path, but attrition increases to 25 per cent.

Of the five scenarios, only C and D come close to meeting the necessary net growth in direct-care workers of 17,000 each year, shown by the dotted line.

The small gap in scenario D could be overcome through productivity improvements, including more efficiently using the current workforce, along with technology and innovation enhancements. But without significant improvement in attrition and new training, plus maintaining at least recent levels of migrant employment in the sector, the gap is likely to be too big to overcome by other means.

While these scenarios are highly dependent on underlying assumptions, they illustrate that getting close to meeting the required growth in workforce necessitates all levers being pulled. Just pulling one lever would be unrealistic – for example, meeting demand through increased training completions alone would require training rates to increase by 125 per cent. Reducing attrition alone would require attrition rates to fall below nine per cent. This challenge cannot be overcome with a single solution.

What is holding back progress?

WAGES

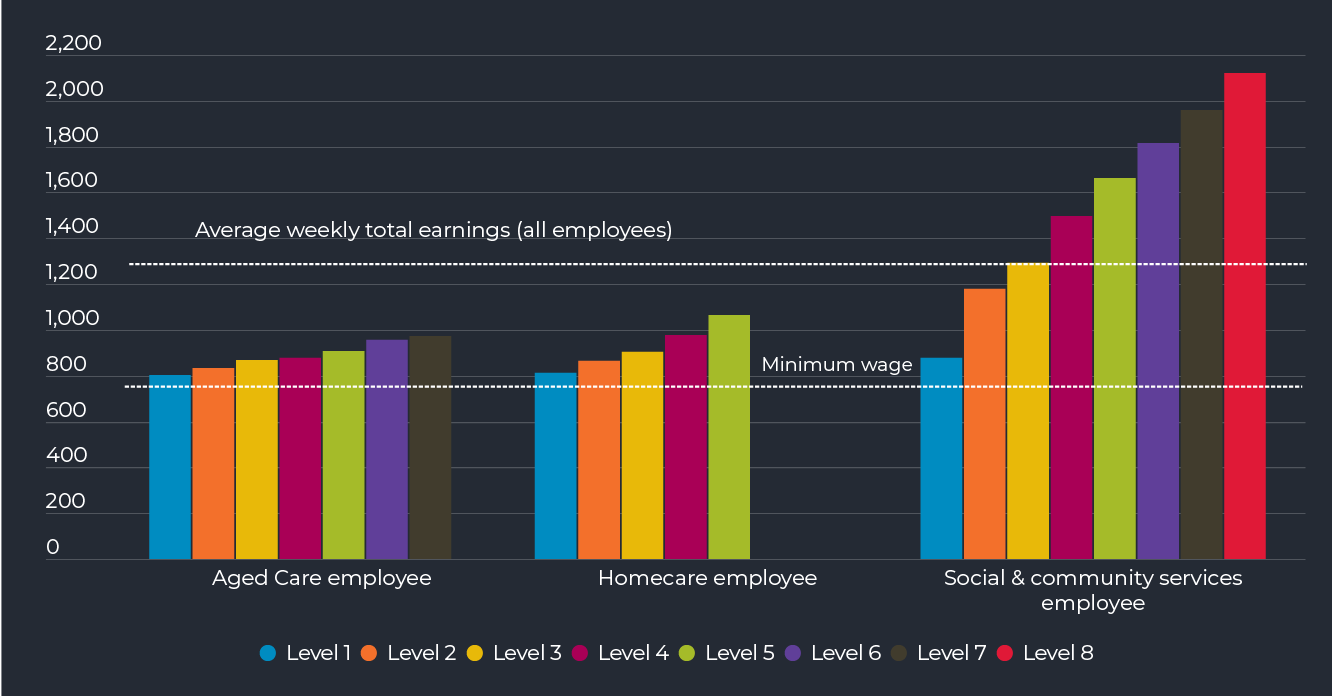

Relatively low wages clearly limit both recruitment and retention in the workforce, and are the source of most workers’

dissatisfaction with their employment.

Increasing demand from other sectors with similar workforce needs, including disability and health, sees these sectors pay more than aged care across all professions. The award wage for personal-care workers with similar skill sets is 25 to 30 per cent lower in aged care than in disability care.

WORKING HOURS

Despite the overall shortage of workers, a considerable proportion of those currently in the sector want to increase their hours. Around 30 per cent of those in residential care and 40 per cent in home care want to work more, and more than 10 per cent hold a second job.

CAREER PROGRESSION

A lack of career progression, training and development is cited by aged-care staff as their main reasons for leaving the industry. There are limited career pathways, particularly for personal-care workers, and wages do not increase much as staff become more senior.

TRAINING AND QUALIFICATIONS

The royal commission recommends a mandatory minimum qualification of a Certificate III for personal-care workers, but the Government has not yet accepted this. In the 2016 workforce census, 12.6 per cent of residential and 14.2 per cent of home-care workers had no qualifications.

PERCEPTIONS OF THE INDUSTRY

Public perceptions of aged-care work tend to be negative and have been further damaged by allegations of poor staff behaviour coming to light during the royal commission. These perceptions do not match the experience of many aged-care workers. The 2016 NACWCS found very high levels of overall job satisfaction across occupation groups.

Workforce planning

Recommendation one

The National Aged Care Workforce Census and Survey (NACWCS) should take place every two years to assist with workforce planning, as recommended by the aged-care royal commission.

Wages and conditions

Recommendation two

Unions, employers and the Federal Government should collaborate to increase award wages in the sector, as recommended by the royal commission.

They should also consider remuneration and award structures that allow pay to rise with increased responsibility, to better enable long-term career progression.

Recommendation three

Employers should focus on improving rostering, including using digital solutions, to better utilise the existing workforce.

Recommendation four

Industry, unions and the Federal Government should review and revise conditions around minimum shift lengths, paid travel time and the cancellation of shifts under the relevant awards.

Training

Recommendation five

A Certificate III should be a mandatory minimum qualification for personal-care workers. Transition arrangements should ensure that the approximately 12 to 14 per cent of the existing workforce without these qualifications can continue to work while gaining this qualification.

Recommendation 6

Extend the Boosting Apprenticeship Commencements scheme for a minimum of two to three years for aged care traineeships.

Recommendation 7

State governments should fully refund fees for Certificate IIIs after graduates have worked in the state’s aged-care sector for a two-year period.

Recommendation 8

Industry should encourage the uptake of already developed and funded training programs for ongoing professional development. Staff should have time to complete this training in their paid working hours.

Recommendation 9

Revise the Certificate III in Individual Support, with a focus on dementia care, palliative care and digital skills. Increase work placement requirements to a minimum of 160 hours across a variety of shifts.

Recommendation 10

Industry and governments should develop low-cost retraining options for those returning to the industry to boost skills and attract workers.

Migration

Recommendation 11

Permanently increase the number of hours international students are allowed to work in the aged-care sector.

Recommendation 12

Permanently add aged care to the specified work requirements to extend working holiday visas, and allow those working in aged care to remain with one employer beyond six months.

Recommendation 13

Recruit personal-care workers directly by adding them to the temporary or permanent skilled-migration lists, or introduce a new “essential skills visa”.

Technology

Recommendation 14

Expand digital literacy training both for new trainees and existing staff.

Recommendation 15

Invest in research on new technologies, with a focus on reducing burdens on workforce. Support the royal commission’s recommendation to introduce an aged-care research and innovation fund, with workforce productivity a key research goal.

Recommendation 16

Develop an aged-care workforce technology cooperative research centre (CRC) with support from industry and all levels of government.

Knowledge sharing

Recommendation 17

The industry should promote best-practice workforce management, including working conditions, training and development programs and technology and innovation.

Recommendation 18

The industry should promote positive changes that take place (such as improved wages and working conditions), along with high levels of job satisfaction in the industry. This should include promotional campaigns to attract workers back to the industry, and new cohorts including job switchers, school leavers and men.