Executive summary

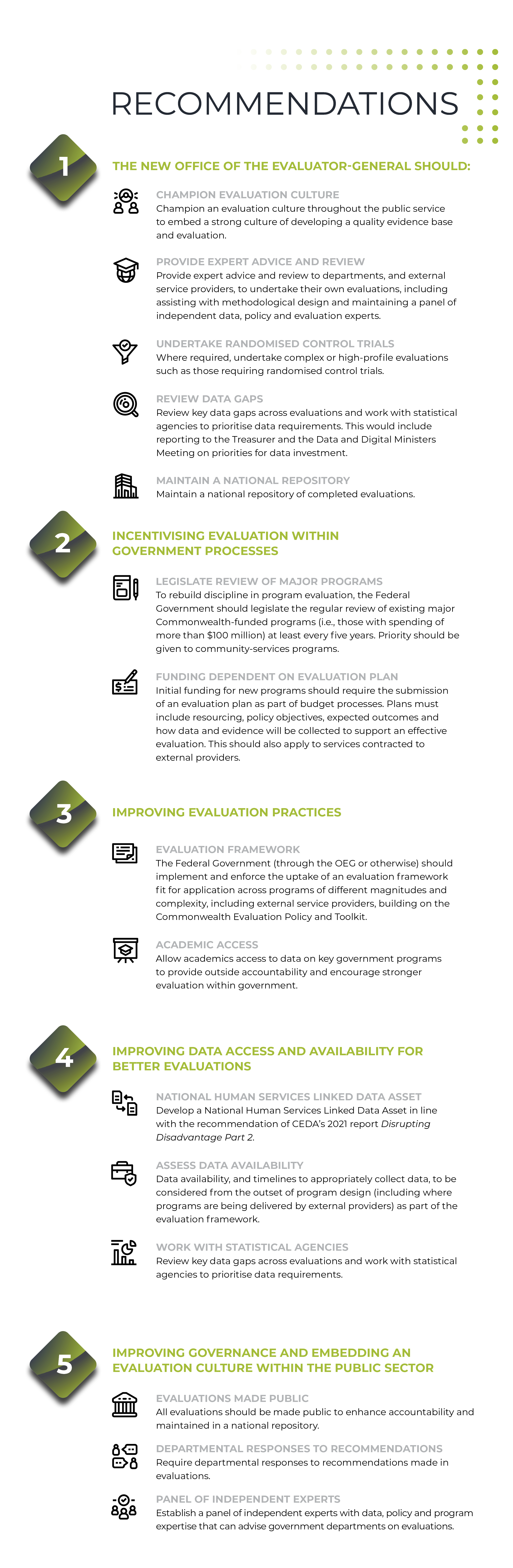

The level of poverty in Australia is unacceptably high and we are not making any progress in reducing poverty and disadvantage. This is in part due to governments’ failure to evaluate community services for their effectiveness and value.

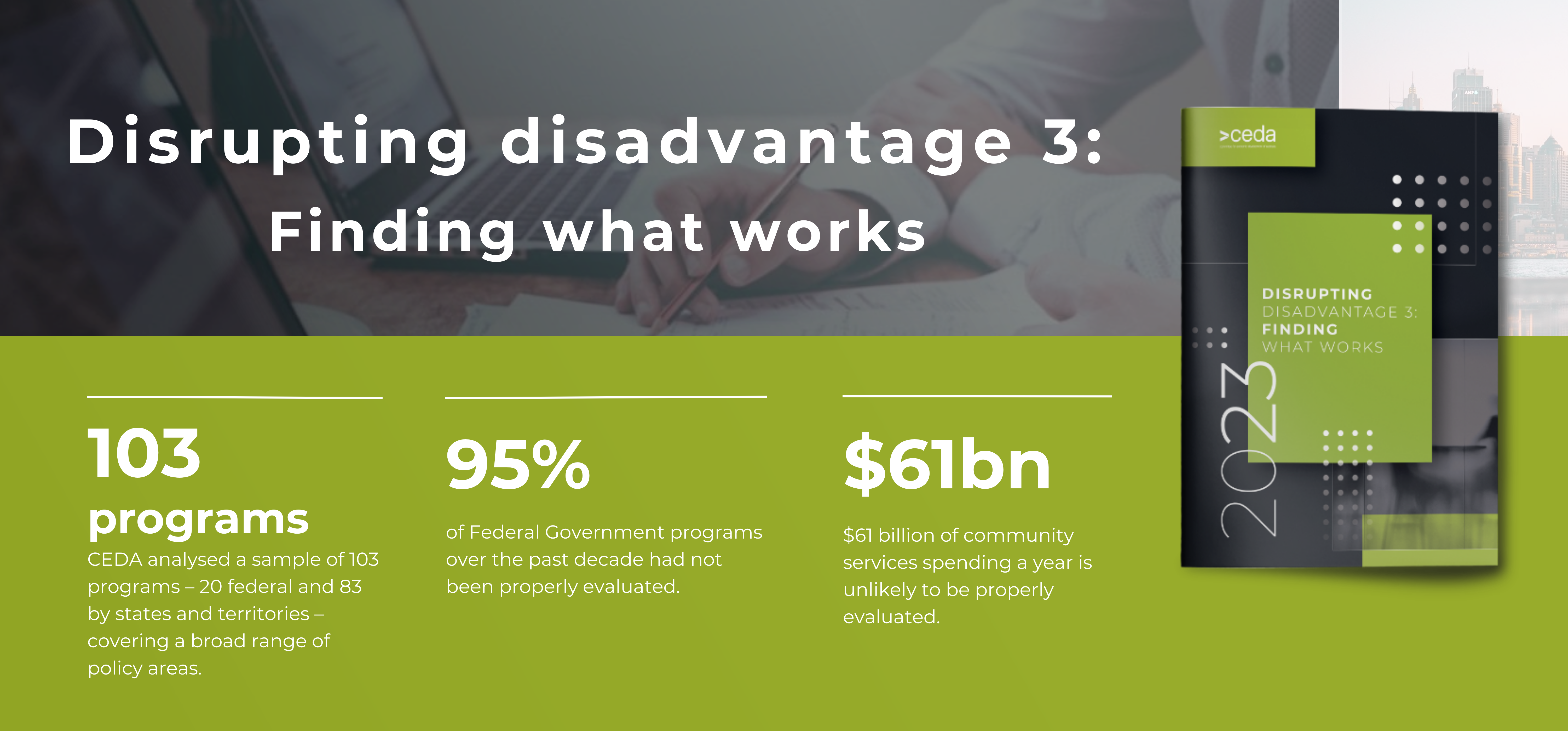

Over the past decade, federal and state government spending on community services has increased by roughly five per cent each year. We cannot continue to increase spending on these programs without properly assessing why they are failing to make tangible progress on reducing poverty and disadvantage (Figure 1).

The community rightfully expects that taxpayer funds are used to effectively improve economic and social outcomes for all citizens, but too often this is not the case.

Without consistent program evaluation and implementing improvements based on data, evidence and analysis, ineffective programs are allowed to continue even as effective programs are stopped.

!function(e,i,n,s){var t="InfogramEmbeds",d=e.getElementsByTagName("script")[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement("script");o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src="https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js",d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,"infogram-async");

AUTHORS

Cassandra Winzar

Cassandra Winzar

Senior Economist, CEDA

.png) Sebastian Tofts-Len

Sebastian Tofts-Len

Graduate Economist, CEDA

Ember Corpuz

Ember Corpuz

Researcher & Economist, CEDA

!function(e,i,n,s){var t="InfogramEmbeds",d=e.getElementsByTagName("script")[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var o=e.createElement("script");o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src="https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js",d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)}}(document,0,"infogram-async");

CEDA’s analysis of program evaluations is sobering. We examined a sample of 20 Federal Government programs with a total program expenditure of more than $200 billion. Ninety-five per cent of these programs were found not to have been properly evaluated. But the Federal Government is not alone in this problem – analysis of state government evaluations shows similar results.

The problems with evaluation start from the outset of program and policy design – many programs were found to lack clear objectives and any definition of “success”. Most programs also do not adequately collect, or plan to collect, data from the outset – impeding the ability to evaluate further on.

Australia has a poor track record on improving evaluation in the public service. Despite multiple reviews and decades of attempted reform to public-sector evaluation process, the results have been ineffective and inconsistent.

This is not due to a lack of good intentions. Policymakers and politicians clearly want to improve the welfare of Australians and we have seen some welcome progress on data availability and sharing across governments.

What is holding back change is a complex system that encourages policymakers to implement rapid responses to societal problems, rather than insisting on regular, proactive evaluation of existing programs. This is compounded by challenges in undertaking evaluations and a lack of resourcing, leading to long-term atrophy of evaluation culture and capability.

Evaluation is important across all policy areas, but we consistently see the failings of poor policy and limited or no improvement in service delivery in the community services designed to tackle entrenched disadvantage. These services must be where government begins its commitment to regular, robust evaluation.

There is plenty of evidence showing what makes a good evaluation and how to conduct it. The bigger issues are cultural change, political will and the capacity and capability within the public sector to work with data and undertake quality evaluations.

The good news is there is growing momentum to change the status quo. With increasing political will, we can finally make some breakthroughs in this area and build on the growing appetite for using data to improve policy design and review.

The Albanese Government appears committed to improving and embedding evaluation culture. It has said it is committed to making evaluation a priority, and it has proposed the establishment of an Office of the Evaluator-General (OEG). Such an office, particularly if given a clear remit and appropriate resourcing, is a good starting point to change the culture and raise the profile of evaluation within government.

CEDA recommends that an OEG would primarily champion and steward evaluation and develop capability and capacity throughout the public service. Evaluation activity would continue to be primarily undertaken at the departmental level. An OEG is not the solution to all the problems with evaluation, but it is the kind of circuit breaker needed to drive change.

Firmly embedding effective evaluation into policies and programs will take time, as it has been neglected for decades. To have true reform, governments need to take the time to carefully implement changes.

Cultural change is particularly difficult, and the tone needs to be set from the top by ministers and senior policymakers. Moving too quickly, or being too ambitious, risks further failure in this space and repeating the mistakes of the past, where evaluation becomes a tick-the-box exercise rather than being meaningfully embraced by policymakers.

If we want to end the ongoing cycle of reviews and inquiries that gather dust on politicians’ desks after the latest policy scandal, evaluation must be integrated into a range of government decision-making and budget processes.

A good starting point is to legislate a regular review of all programs. Evaluation must be part of any policy or program design from the very beginning, with clearly stated outcomes and objectives. Government also must invest in developing data assets and data availability and upskilling public servants to improve capacity and capability.

The role of data cannot be understated. Without appropriate planning to collect, analyse and link data from the outset of program design, evaluations will not be successful. This needs to be funded as part of the program resourcing – including where programs are delivered by external providers.

Evaluations are key to improving government accountability and transparency, and should be made publicly available and accessible to the broader community. The community should be able to hold the government to account for the success of its programs and policies. Currently, we do not have the information to do so.

We have seen some good progress on data sharing in recent years across governments. Momentum appears to be growing around reforming evaluation practices. Now is the time to build on these good intentions to truly reform the culture and capability of evaluation in Australia.

Australia will be choosing to perpetuate the cycle of disadvantage if we do not proactively respond to poor past performance and evidence of policy shortcomings.